Rev. José Mario O. Mandía

Jesus Christ had sent His apostles to preach the Gospel to the whole world. Hence, the Faith not only spread among Greek and Latin-speaking peoples. It reached places which were not yet influenced by Greek culture, places where the Semitic languages were spoken. The term ‘Semitic’ comes from Shem, the name of one of the three sons of Noah (cf. Genesis 5-11), and was coined in the 18th century to designate the languages closely related to Arabic, Aramaic, and Hebrew.

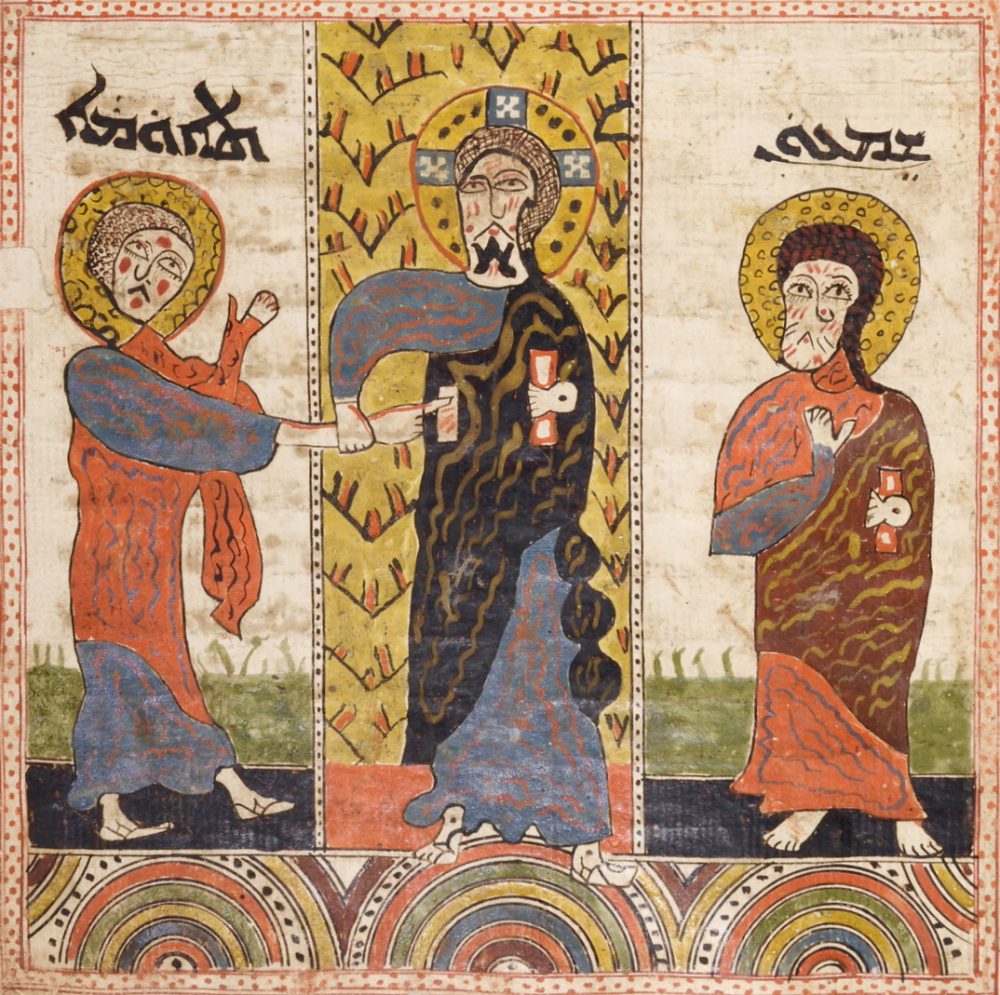

“These Churches developed throughout the fourth century in the Near East, from the Holy Land to Lebanon and to Mesopotamia. In that century, which was a period of formation on the ecclesial and literary level, these communities contributed to the ascetic-monastic phenomenon with autochthonous characteristics that did not come under Egyptian monastic influence. The Syriac communities of the fourth century, therefore, represent the Semitic world from which the Bible itself has come, and they are an expression of a Christianity whose theological formulation had not yet entered into contact with different cultural currents, but lived in their own way of thinking. They are Churches in which asceticism in its various hermetic forms (hermits in the desert, caverns, recluses, stylites) and monasticism in forms of community life, exert a role of vital importance in the development of theological and spiritual thought” (Benedict XVI, General Audience, 21 November 2007).

Just as we find writers among the Greeks and Latins, we also find them among the Syrians. Foremost among these writers is Aphraates (c. 280 – c. 345) who was of Iranian descent and was called the ‘Persian Sage.’ He himself wrote that his parents were pagan but he later converted to Christianity after which “he embraced the religious life, and was later elevated to the episcopate, on which occasion he assumed the Christian name of Jacob” (“Aphraates,” Catholic Encyclopedia. https://newadvent.org/cathen/01593c.htm).

Aphraates (or Aprahat) “wrote 23 homilies, known as Expositions or Demonstrations, on various aspects of Christian life, such as faith, love, fasting, humility, prayer, the ascetic life, and also the relationship between Judaism and Christianity, between the Old and New Testaments. He wrote in a simple style with short sentences and sometimes with contrasting parallelisms; nevertheless, he was able to weave consistent discourses with a well-articulated development of the various arguments he treated” (Benedict XVI, General Audience, 21 November 2007).

The first four demonstrations were on faith, charity, fasting and prayer. This reveals to us what was foremost in the mind of Aphraates. “Faith … makes sincere charity possible, which expresses itself in love for God and neighbor. Another important aspect in Aphraates’ thought is fasting, which he understood in a broad sense. He spoke of fasting from food as a necessary practice to be charitable and pure, of fasting understood as continence with a view to holiness, of fasting from vain or detestable words, of fasting from anger, of fasting from the possession of goods with a view to ministry, of fasting from sleep to be watchful in prayer” (Benedict XVI, General Audience, 21 November 2007).

Aphraates also reaffirmed Church teachings such as Our Lady’s perpetual virginity and her role as Mother of God, Saint Peter’s role as foundation of the Church, and the doctrine of the sacraments.

“In regard to the Holy Eucharist, Aphraates affirms that it is the real Body and Blood of Christ. In the seventh ‘Demonstration’, he treats of penance and penitents, and represents the priest as a physician who is charged with the healing of a man’s wounds. The sinner must make known to the physician his infirmities in order to be healed, i.e. he must confess his sins to the priest, who is bound to secrecy. Because of the numerous quotations from Holy Writ used by Aphraates, his writings are also very valuable for the history of the canon of Sacred Scripture and of exegesis in the early Mesopotamian Church” (“Aphraates,” Catholic Encyclopedia. https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01593c.htm).

Regarding prayer, Aphraates says that its aim is to make Christ dwell in one’s heart, and this presence of Christ leads one to practice charity.

“Give relief to those in distress, visit the ailing,

help the poor: this is prayer.

Prayer is good, and its works are beautiful.

Prayer is accepted when it gives relief to one’s neighbor.

Prayer is heard when it includes forgiveness of affronts.

Prayer is strong

when it is full of God’s strength” (Expositions 4, 14-16).

Follow

Follow