Rev. José Mario O. Mandía

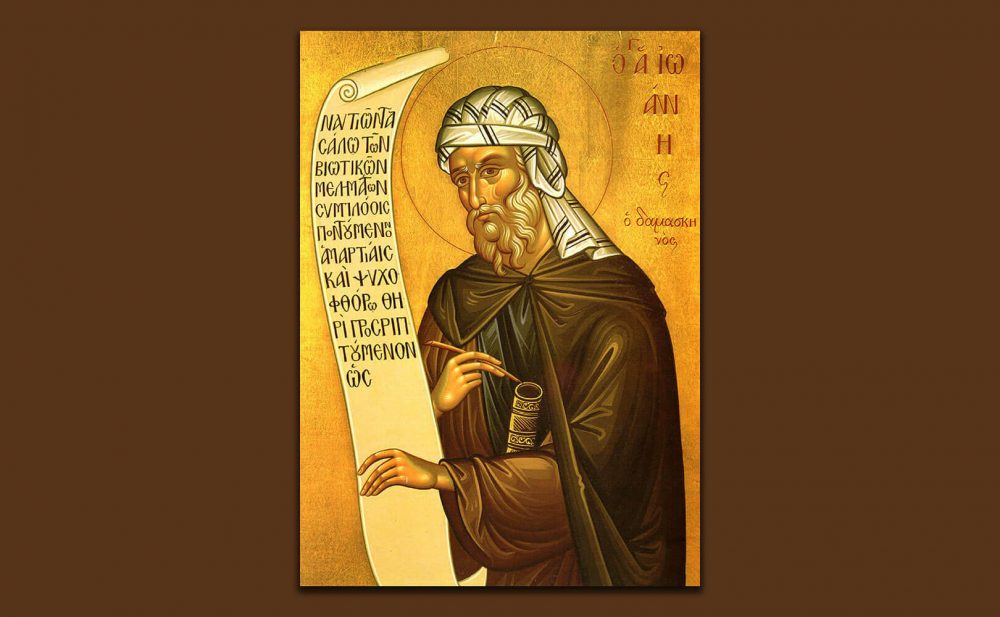

Finally, we come to John of Damascus (or John Damascene), whom many regard as the last of the Fathers of the Church. Saint John, like his contemporary Germanus of Constantinople (see Church Fathers, 55), was a great defender of the importance of sacred images and icons.

Pope Benedict XVI summarizes his life as follows: “John, born into a wealthy Christian family, at an early age assumed the role, perhaps already held by his father, of Treasurer of the Caliphate. Very soon, however, dissatisfied with life at court, he decided on a monastic life, and entered the monastery of Mar Saba, near Jerusalem. This was around the year 700. He never again left the monastery, but dedicated all his energy to ascesis and literary work, not disdaining a certain amount of pastoral activity, as is shown by his numerous homilies” (General Address, 6 May 2009).

Aside from his defense of icons, St John also explained the concept of circumincession (perichoresis in Greek; circumincessio in Latin) in the Blessed Trinity which teaches that each of the three Divine Persons is present in the other two [Persons] since the three have one and the same Divine Essence. In Book 1 of his famous work An Exposition of the Orthodox Faith, he wrote: “God is One, that is to say, one essence; and that He is known, and has His being in three subsistences [Persons], in Father, I say, and Son and Holy Spirit; and that the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit are one in all respects, except in that of not being begotten, that of being begotten, and that of procession….” The Exposition of the Orthodox Faith is considered the Eastern Church version of Saint Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologiae.

Moreover, his love for poetry and music became the medium through which he spoke about the Assumption of Our Lady. He is, in fact, called ‘The Doctor of the Assumption.’

Let us return to the issue of icons as this was the burning issue of the times of Saint John. Even the Islamic believers fell into iconocasm, having adopted the Jewish practice of not using images for the cult. Saint John’s three Discourses argued against those who reject the holy images and his teachings found their way to the 7th Ecumenical Council – the Council of Nicaea (787).

Pope Benedict XVI adds that “John Damascene was also among the first to distinguish, in the cult, both public and private, of the Christians, between worship (latreia), and veneration (proskynesis): the first can only be offered to God, spiritual above all else, the second, on the other hand, can make use of an image to address the one whom the image represents. Obviously, the Saint can in no way be identified with the material of which the icon is composed” (General Address, 6 May 2009).

Pope Francis has stressed this point in his latest encyclical Dilexit nos (no. 50): “Whatever the image employed, it is clear that the living heart of Christ – not its representation – is the object of our worship, for it is part of his holy risen body, which is inseparable from the Son of God who assumed that body forever. We worship it because it is ‘the heart of the Person of the Word, to whom it is inseparably united’ [Pius VI, Constitution Auctorem Fidei (28 August 1794)].”

The Holy Father adds: “Nor do we worship it for its own sake, but because with this heart the incarnate Son is alive, loves us and receives our love in return. Any act of love or worship of his heart is thus ‘really and truly given to Christ himself’ [Leo XIII, Encyclical Letter Annum Sacrum (25 May 1899)] since it spontaneously refers back to him and is ‘a symbol and a tender image of the infinite love of Jesus Christ’ [Ibid: ‘Inest in Sacro Corde symbolum et expressa imago infinitæ Iesu Christi caritatis’].”

As we have seen in CCCC 446, the Incarnation is what explains the importance of images. Damascene argued: “In other ages God had not been represented in images, being incorporate and faceless. But since God has now been seen in the flesh, and lived among men, I represent that part of God which is visible. I do not venerate matter, but the Creator of matter, who became matter for my sake and deigned to live in matter and bring about my salvation through matter. I will not cease therefore to venerate that matter through which my salvation was achieved. But I do not venerate it in absolute terms as God! How could that which, from non-existence, has been given existence, be God?… But I also venerate and respect all the rest of matter which has brought me salvation, since it is full of energy and Holy graces. Is not the wood of the Cross, three times blessed, matter?… And the ink, and the most Holy Book of the Gospels, are they not matter? The redeeming altar which dispenses the Bread of life, is it not matter?… And, before all else, are not the flesh and blood of Our Lord matter? Either we must suppress the sacred nature of all these things, or we must concede to the tradition of the Church the veneration of the images of God and that of the friends of God who are sanctified by the name they bear, and for this reason are possessed by the grace of the Holy Spirit. Do not, therefore, offend matter: it is not contemptible, because nothing that God has made is contemptible” (Contra imaginum calumniatores, I, 16, ed. Kotter, pp. 89-90).

This role of matter is what, in recent times, Saint Josemaría Escrivá taught. “What are the sacraments, which people in early times described as the footprints of the Incarnate Word, if not the clearest expression of this way which God has chosen in order to sanctify us and to lead us to heaven? Don’t you see that each sacrament is the love of God, with all its creative and redemptive power, given to us through the medium of material things? What is this Eucharist which we are about to celebrate if not the Adorable Body and Blood of our Redeemer, which is offered to us through the lowly matter of this world (wine and bread), through the elements of nature, cultivated by man as the recent Ecumenical Council has reminded us” (Homily “Passionately Loving the World”).

Moreover, Saint John extends this to the veneration of the relics of the saints. They have become sharers in Christ’s Resurrection, and therefore are like God. This similarity is the reason we honor them and their relics, though we do not worship them.

It is believed that John died in his monastery, Mar Saba, near Jerusalem on 4 December 749 AD.

Editor's note: Rev. José Mario O. Mandía returns at the beginning of January 2025, with a new weekly column.

Follow

Follow