Rev. José Mario O. Mandía

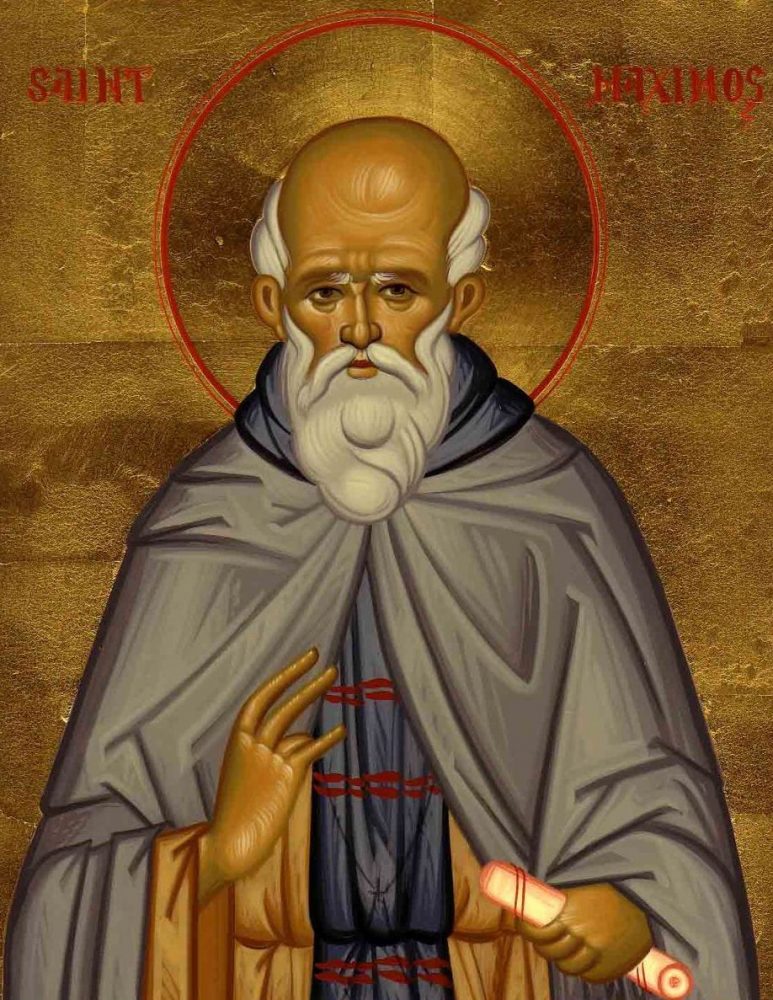

We turn our attention to one of the great Fathers of the Eastern Church, Saint Maximus the Confessor. A confessor is one who gives witness to his or her faith not through death but through suffering such as imprisonment, torture, exile, or forced labor.

Maximus was born in Palestine around the year 580 to a noble family. In his youth, he was introduced to the monastic life. He learned Scriptures through the works of Origen (cf. Church Fathers 15 & 16). At a certain point, he became first secretary to the Emperor Heraclius who valued his services. But the monastic life attracted him more and so went to a monastery in Chrysopolis.

He moved from Jerusalem to Constantinople, but because of the barbarian invasions, he fled to Africa. He showed great boldness in defending orthodoxy especially against monothelitism which argued that Christ had only one will (the divine will), not two (human and divine). It seemed reasonable to say that Christ had only one will, but Saint Maximus knew that if Jesus was true Man, he should have a human intellect and a human will. Without a human will, he would not be human, and if he were not human (and only divine), he could not suffer and die for us. But no, he insisted, Christ is not only fully divine but also fully man. But how does Christ achieve unity? By uniting his human will with the divine.

The agony in the garden shows us, on one hand, the two wills in Jesus and, on the other, their unity: “My Father, if it be possible, let this cup pass from me; nevertheless, not as I will, but as thou wilt” (Matthew 26:40; cf. Mark 14:36; Luke 22:42).

Pope Benedict comments: “St Maximus demonstrates that man does not find his unity, the integration of himself or his totality within himself but by surpassing himself, by coming out of himself. Thus, also in Christ, by coming out of himself, man finds himself in God, in the Son of God. … The height of freedom is the ‘yes’, in conformity with God’s will. It is only in the ‘yes’ that man truly becomes himself; only in the great openness of the ‘yes’, in the unification of his will with the divine, that man becomes immensely open, becomes ‘divine’.

“What Adam wanted was to be like God, that is, to be completely free. But the person who withdraws into himself is not divine, is not completely free; he is freed by emerging from himself, it is in the ‘yes’ that he becomes free; and this is the drama of Gethsemane: not my will but yours” (General Address, 25 June 2008).

The monothelite heresy was not only a religious question but a political one. The emperor wanted everyone to subscribe to this false doctrine in order to forge unity. The Emperor had already condemned Pope Martin I to death for defending the two wills of Christ. Eventually commuted the sentence into permanent exile in Crimea, where the Pope died on 16 September 655.

“It was Maximus’ turn shortly afterwards, in 662, as he too opposed the Emperor, repeating: “It cannot be said that Christ has a single will!” (cf. PG 91, cc. 268-269). Thus, together with his two disciples, both called Anastasius, Maximus was subjected to an exhausting trial although he was then over 80 years of age. The Emperor’s tribunal condemned him with the accusation of heresy, sentencing him to the cruel mutilation of his tongue and his right hand – the two organs through which, by words and writing, Maximus had fought the erroneous doctrine of the single will of Christ. In the end, thus mutilated, the holy monk was finally exiled to the region of Colchis on the Black Sea where he died, worn out by the suffering he had endured, at the age of 82, on 13 August that same year, 662” (Benedict XVI, General Address, 25 June 2008).

Saint Maximus did not only write theological works. Having experienced suffering first hand, he wrote about the ascetical struggle. Here are two sample passages from his works.

“Whenever you are suffering intensely from insult or disgrace, realize that this can be of great benefit to you, for disgrace is God’s way of driving vainglory out of you” (Maximus Confessor: Selected Writings. Classics of Western Spirituality. Paulist Press , 1985, p. 38).

“There are certain things which check the passions in their movement and do not allow them to advance and increase, and there are others which diminish them and make them decrease. For example, fasting, hard labor, and vigils do not allow concupiscence to grow, while solitude, contemplation, prayer, and desire for God decrease it and make it disappear. And similarly is this the case with anger: for example, long-suffering, the forgetting of offenses, and meekness check it and do not allow it to grow, while love, almsgiving, kindness, and benevolence make it diminish” (ibid., p. 53).

Follow

Follow