Rev. José Mario O. Mandía

jmom.honlam.org

In the General Audience of 25 April 2007, Pope Benedict XVI mentioned that Origen brought about an “irreversible turning point” in “the history of theology and Christian thought.” The Holy Father pointed out that this turning point consists in basing theology on the explanation of Scriptures. He is “the first scientific exegete of the Catholic Church” and can thus be considered the “founder of biblical science” (Quasten, II, pp. 44-45).

Origen’s “first principle is that the Bible is the Word of God, not a dead word imprisoned in the past, but a living word addressed immediately to the man of today. His second principle is that the Old Testament is illuminated by the New, just as the New only discloses its profundity once it is illuminated by the Old. The bond between the two is determined by allegory” (Quasten II, p. 92). In order to understand Sacred Scripture, one has to know the literal sense, the moral sense, and the spiritual or mystical sense. In the 4th century, St Augustine would expand these senses of Scripture to four (cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church, 115-119).

In his work Hexapla (“six-column Bible”), Origen shows his desire to understand the Bible in its literal sense. The columns were arranged as follows: (1) Hebrew text of the Bible; (2) Hebrew text in Greek characters (as a pronunciation guide); (3) Greek translation by Aquila; (4) Greek translation by Symmachus; (5) Greek translation in the Septuagint; (6) Greek translation by Theodotion (cf. Quasten II, p. 44). The last four columns provided a guide to the correct interpretation of the text.

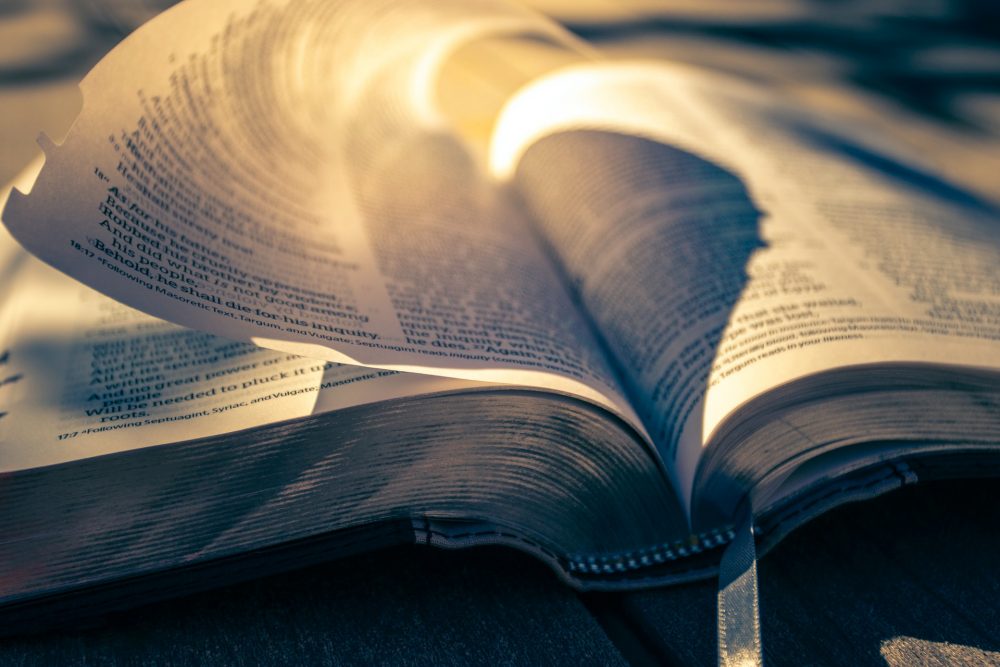

For Origen, however, knowledge of the Scripture was not enough. One needed to pray with Scripture and fall in love with Christ as a consequence (cf. Pope Benedict XVI General Audience, 2 May 2007). Origen explained this need to know through love based on the Hebrew meaning of the verb ‘to know’ which can include the human act of love, as in the passage in Genesis 4:1: “Adam knew Eve his wife, and she conceived.” In order to achieve this love, Origen recommended lectio divina.

Pope Benedict quotes Origen’s recommendation in his Letter to Gregory: “Study first of all the lectio [reading] of the divine Scriptures. Study them, I say. For we need to study the divine writings deeply… and while you study these divine works with a believing and God-pleasing intention, knock at that which is closed in them and it shall be opened to you by the porter, of whom Jesus says, ‘To him the gatekeeper opens’ (John 10:3).

“While you attend to this lectio divina, seek aright and with unwavering faith in God the hidden sense which is present in most passages of the divine Scriptures. And do not be content with knocking and seeking, for what is absolutely necessary for understanding divine things is oratio, and in urging us to this the Saviour says not only ‘knock and it will be opened to you,’ and ‘seek and you will find,’ but also ‘ask and it will be given you’ (Ep. Gr. 4).”

In the 4th century, Bishop Ambrose of Milan would learn this from Origen’s works and handed them on to St Augustine and to the monastic life that he inspired.

In the 6th century, Benedict of Nursia took it up and by the 12th century, it was taught as a four-step process by the Carthusian monk Guigo II: lectio, meditatio, oratio, contemplatio (reading, meditation, prayer, contemplation).

In his Apostolic Exhortation Verbum Domini, 87 (2010), Pope Benedict described the steps in doing the lectio.

“It opens with the reading (lectio) of a text, which leads to a desire to understand its true content: what does the biblical text say in itself? Without this, there is always a risk that the text will become a pretext for never moving beyond our own ideas. Next comes meditation (meditatio), which asks: what does the biblical text say to us? Here, each person, individually but also as a member of the community, must let himself or herself be moved and challenged. Following this comes prayer (oratio), which asks the question: what do we say to the Lord in response to his word? Prayer, as petition, intercession, thanksgiving and praise, is the primary way by which the word transforms us. Finally, lectio divina concludes with contemplation (contemplatio), during which we take up, as a gift from God, his own way of seeing and judging reality, and ask ourselves what conversion of mind, heart and life is the Lord asking of us? In the Letter to the Romans, Saint Paul tells us: ‘Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that you may prove what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect’ (12:2). Contemplation aims at creating within us a truly wise and discerning vision of reality, as God sees it, and at forming within us ‘the mind of Christ’ (1 Corinthians 2:16). The word of God appears here as a criterion for discernment: it is ‘living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing to the division of soul and spirit, of joints and marrow, and discerning the thoughts and intentions of the heart’ (Hebrews 4:12). We do well also to remember that the process of lectio divina is not concluded until it arrives at action (actio), which moves the believer to make his or her life a gift for others in charity.”

Follow

Follow