Rev. José Mario O. Mandía

jmom.honlam.org

The Apostolic and Sub-apostolic Fathers worked to defend the faith and explain it. As the Church grew, there was a need to make a more systematic, all-encompassing and precise exposition of the Faith to teach the new converts. Thus, the theological schools were formed. The most famous of these theological schools was the one in Alexandria in Egypt.

Alexandria was founded in 331 BC by Alexander the Great. It was the birthplace of Hellenism and became a center of intellectual life. But it was not exclusively Hellenistic, because Greek culture encountered and mingled with Oriental, Egyptian and Jewish cultures. It was in Alexandria where the Old Testament was translated to Greek around the 3rd and 2nd century BC.

The meeting between Greek thought and Jewish faith is personified by Philo of Alexandria (or Philo Judaeus) who lived in the first half of the first century in Alexandria. He brought Greek philosophy (particularly that of Plato) into contact with Judaism.

The advent of Christianity “led to the foundation of a theological school. The school of Alexandria is the oldest center of sacred science in the history of Christianity. The environment in which it developed gave it its distinctive characteristics, predominant interest in the metaphysical investigation of the content of the faith, a leaning to the philosophy of Plato, and the allegorical interpretation of Sacred Scripture. It counted among its students and teachers such famous theologians as Clement [of Alexandria], Origen, Dionysius, Pierius, Peter, Athanasius, Didymus and Cyril” (Quasten, II, p. 2).

Clement of Alexandria, probably born in Athens around the year 150 AD, was among the prominent Fathers of this time. His parents were pagan but he became a Christian and traveled to Italy, Syria and Palestine to receive instruction from renowned Christian teachers. His search brought him to Alexandria where he settled down and succeeded his teacher Pantaenus as head of the School of Alexandria.

There is a certain parallelism between Clement of Alexandria and Justin (cf. Church Fathers 10). Justin was born 50 years before Clement, of pagan parents, and also went in search of the truth, aiming “to build a bridge between Christianity and pagan philosophy” (Quasten, I, p 198).

Clement saw the threat of Gnosticism from the Hellenistic environment, but instead of merely criticizing it, he proceeded to “set up a true and Christian Gnosis, which placed in the service of the faith the treasure of truth to be found in the various systems of philosophy. Whereas Gnostic heretics taught that faith and knowledge cannot be reconciled because they are contradictions, Clement endeavors to prove that they are akin to each other and that a harmony of faith (Gr. Pistis) and knowledge (Gr. Gnosis) produces the perfect Christian and the true Gnostic. The beginning and foundation of philosophy is faith. It is, moreover, of the greatest importance to any Christian who wishes to penetrate the content of his faith by reason. At the same time, philosophy proves that the attacks of the enemies against the Christian religion are without foundation” (Quasten, II, p. 20). In his work Stromata, Clement affirms: “Faith is something superior to knowledge and is its criterion” (Book 2, Chapter 4, 15).

And just as Justin argued that creation and salvation is fulfilled in the Logos (Eternal Word, Reason, Jesus Christ), Clement also pointed to Jesus Christ, the Word of God, as the exhorter, the tutor, and the Master.

In the General Audience of 18 April 2007, Pope Benedict XVI said, “As my venerable Predecessor John Paul II wrote in his Encyclical Fides et Ratio, Clement of Alexandria understood philosophy ‘as instruction which prepared for Christian faith’ (n. 38). And in fact, Clement reached the point of maintaining that God gave philosophy to the Greeks ‘as their own [Old] Testament’ (Stromata Book 6, Chapter 8, 67, 1).

“For him, the Greek philosophical tradition, almost like the Law for the Jews, was a sphere of ‘revelation’; they were two streams which flowed ultimately to the Logos himself.

“Thus, Clement continued to mark out with determination the path of those who desire ‘to account’ [cf. I Peter 3:15] for their own faith in Jesus Christ. He can serve as an example to Christians, catechists and theologians of our time, whom, in the same Encyclical, John Paul II urged ‘to recover and express to the full the metaphysical dimension of faith in order to enter into a demanding critical dialogue with both contemporary philosophical thought and with the philosophical tradition in all its aspects.’

“Let us conclude by making our own a few words from the famous ‘prayer to Christ the Logos’ with which Clement concludes his Paedagogus. He implores: ‘Be gracious… to us your children…. Grant us that we may live in your peace, be transferred to your city, sail over the billows of sin without capsizing, be gently wafted by your Holy Spirit, by ineffable Wisdom, by night and day to the perfect day… giving thanks and praise to the one Father… to the Son, Instructor and Teacher, with the Holy Spirit. Amen!’ (Paedagogus, Book 3, Chapter 12, 101).

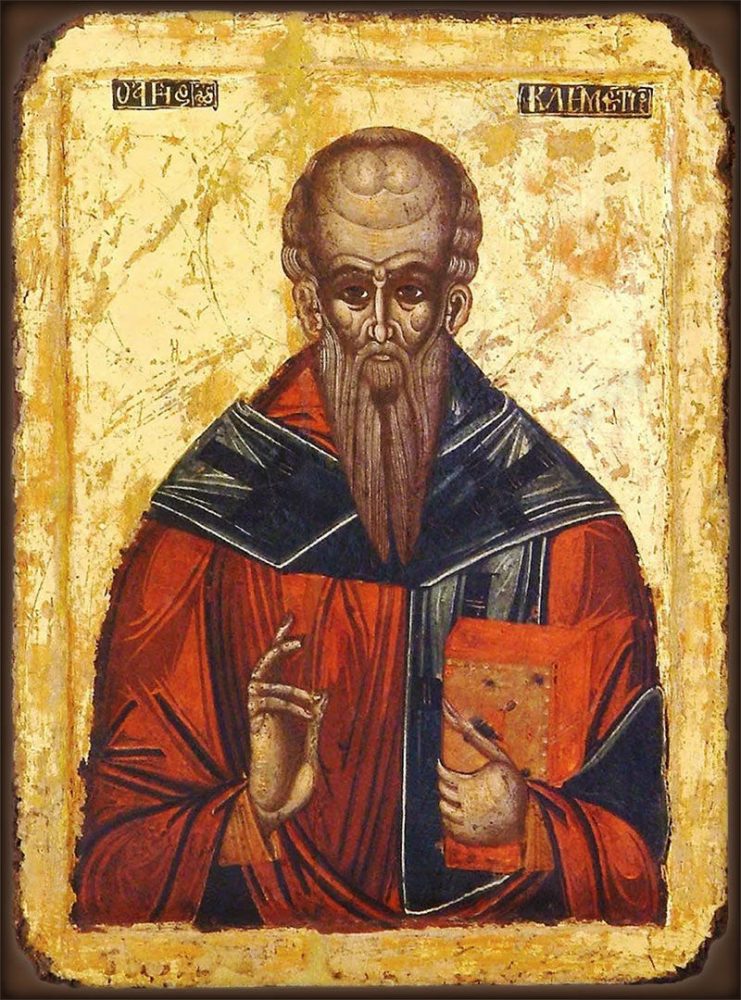

(Image: Clement of Alexandria)

Follow

Follow