Rev. José Mario O. Mandía

jmom.honlam.org

We have previously seen how the early Fathers of the Church endeavored to explain the faith to believers, while at the same time confronting two external threats coming from Judaism and paganism.

But there arose also two internal threats, two heresies which were quite opposite to each other: namely, Gnosticism and Montanism. Both schools of thought gained many followers. Gnosticism was the more dangerous of the two.

Gnosticism wanted a Christianity that conformed to the world, fitted into the culture of the time, absorbed myths and Greek philosophy, and gave little room for Revelation. They ignored the Lord’s declaration before Pilate: “My kingship is not of this world” (John 18:36). It was thus a threat to the spiritual nature of the Church.

Montanism, on the other hand, taught that Christians should flee from the world. The Montanists believed that the world was ending soon, and to prepare for this, Christians must dissociate themselves from anything that is worldly. This is so different from what the Christian believes: that the world is good (cf. Genesis 1:4) and that it is man’s task to “to till it and keep it” (Genesis 2:15). We can see that Montanism was a threat to the Church’s mission to purify and sanctify all earthly realities.

Gnosticism actually dates from pre-Christian times. It arose as a mixture of Oriental religion and Greek philosophy during the time of Alexander the Great (356-323 BC). “From the Oriental religions, Gnosticism inherited the belief in an absolute dualism between God and the world, between soul and body, the derivation of good and bad from two fundamentally different principles and substances, and the longing for redemption and immortality. From Greek philosophy, Gnosticism received its speculative element. Thus, the speculations concerning mediators between God and the world were incorporated from Neo-Platonism; a naturalistic kind of mysticism from Neo-Pythagoreanism; and the appreciation of the individual and his ethical task from Neo-Stoicism” (Quasten, I, pp 254-255). Simon Magus, whom we read about in the Acts of the Apostles (8:9-24), is the last representative of this pre-Christian Gnosticism.

When highly-educated pre-Christian Gnostics converted to the Faith, they brought their belief with them, adding Christian doctrines to their Gnostic views.

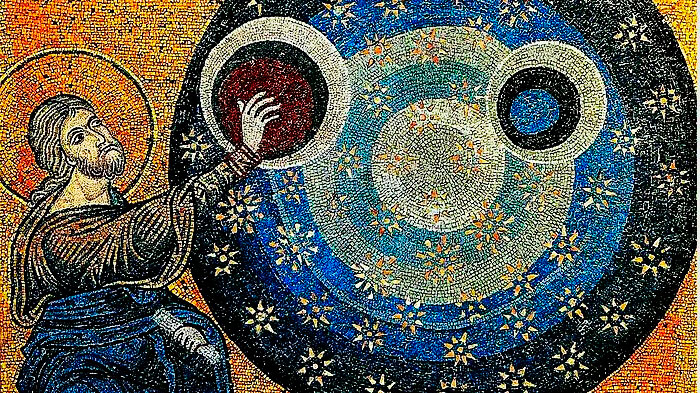

They believed in a good transcendent God who created everything. But there was also a lesser divine figure – the ‘Demiurge’ – that shaped or molded (not created) material reality. The Demiurge was evil and hence, the material creation that it shaped is also evil. The word Demiurge (‘demiurgus’ in Latin, from the Greek ‘dēmiurgós’) originally meant ‘craftsman’ or ‘artisan,’ but eventually came to mean ‘producer.’ The word never strictly meant ‘creator’ or ‘one who produces out of nothing.’

Christ was sent by the good transcendent God to rescue man from the power of the Demiurge. By having an esoteric knowledge (Greek gnosis, ‘knowledge’; gnostikos, ‘good at knowing’) of Christ that only a few persons could attain, one was redeemed. Note that they taught that salvation came through knowledge (not through obedience of the intellect and will to God).

The Church addressed these heresies in two ways.

Firstly, the ecclesiastical authorities excommunicated the heretics and those who followed them. They also warned the faithful about the errors through pastoral letters.

Secondly, theological writers supported the move of the church authorities by showing the errors of the heretics and explaining the doctrine of the Church using Scripture and Tradition. Their writings comprise what are called anti-heretical literature. Unfortunately, not many of these writings have survived to our times.

Follow

Follow