Rev. José Mario O. Mandía

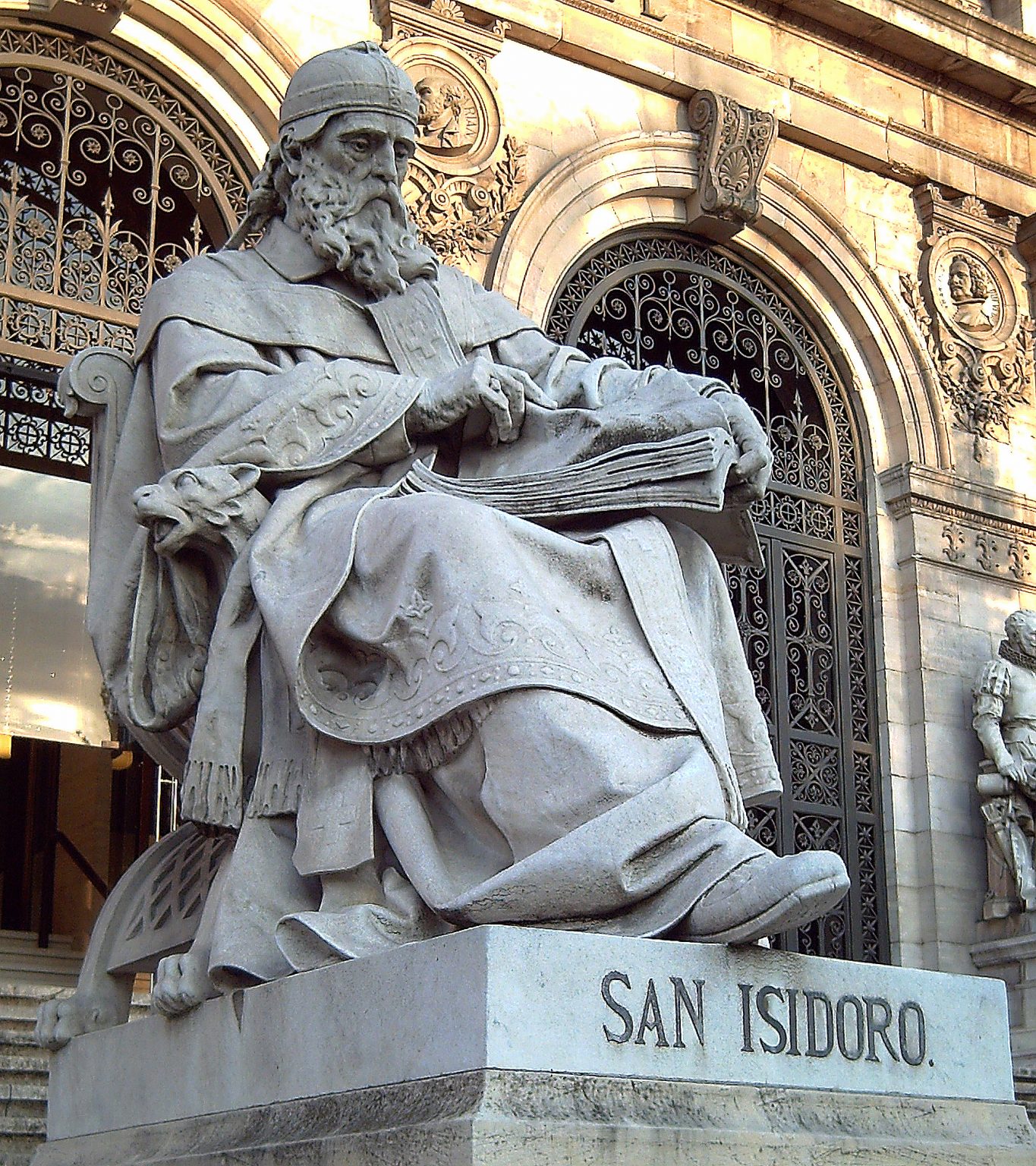

Today we will talk about Isidore of Seville, “the last scholar of the ancient world” (Montalembert, Charles F. Les Moines d’Occident depuis Saint Benoît jusqu’à Saint Bernard [The Monks of the West from Saint Benedict to Saint Bernard]. Paris: J. Lecoffre, 1860). The Council of Toledo in 653 described him as “an illustrious teacher of our time and the glory of the Catholic Church.”

Born in Cartagena, Spain, about 560 AD, to a devout and cultured Catholic family, Isidore was educated under his older brother Leander, bishop of Seville. Isidore mastered Latin, aside from learning Greek and Hebrew. His brother was an exacting mentor. Their house had a library with an abundant collection of classical, pagan and Christian works. Eventually, Isidore would succeed his brother around 599. His younger brother Fulgentius became bishop of Astigi. His sister Florentina was a nun. All four siblings are venerated as saints.

In those times, Visigoths and Arians had invaded the Iberian Peninsula. This mingling was bringing about a new civilization. The Visigoths were in full control of Spain. Their barbaric ways and contempt of learning threatened the country. Saint Isidore harnessed religious and educational resources to bring about a homogeneous nation which assimilated these foreign invaders. He succeeded in merging the different elements. He was also able to eradicate Arianism, which was prevalent among the Visigoths.

After his death on April 4, 636, his fame spread thanks to his work Etymologiae, which was a sort of encyclopedia that put together many books from antiquity, thus saving them from oblivion. It is also said that this work helped standardize punctuation, particularly the period (or full stop), the comma and the colon. It was widely used in educational institutions during the Middle Ages.

Despite his effective leadership, Saint Isidore was caught “between a desire for solitude to dedicate himself solely to meditation on the word of God, and the demands of charity to his brethren…” (Pope Benedict XVI, General Address, 18 June 2008).

Pope Benedict XVI gives the following example from Isidore’s writings: “The man responsible for a Church (vir ecclesiasticus) must on the one hand allow himself to be crucified to the world with the mortification of his flesh, and on the other, accept the decision of the ecclesiastical order – when it comes from God’s will – to devote himself humbly to government, even if he does not wish to” (Sententiarum liber III, 33, 1: PL 83, col 705 B).

Then he goes on: “Men of God (sancti viri) do not in fact desire to dedicate themselves to things of the world and groan when by some mysterious design of God they are charged with certain responsibilities…. They do their utmost to avoid them but accept what they would like to shun and do what they would have preferred to avoid. Indeed, they enter into the secrecy of the heart and seek there to understand what God’s mysterious will is asking of them. And when they realize that they must submit to God’s plans, they bend their hearts to the yoke of the divine decision” (Sententiarum liber III, 33, 3: PL 83, coll. 705-706).

In comparing the active and the contemplative life, he wrote: “The middle way, consisting of both of these forms of life, normally turns out to be more useful in resolving those tensions which are often aggravated by the choice of a single way of life and are instead better tempered by an alternation of the two forms” (Differentiarum, Book II, 34, 134).

He cited the fact that our Lord himself showed us this example: living the active life when he worked signs and miracles, but living the contemplative life when he spent the night on the mountain praying.

He concludes: “Therefore let the servant of God, imitating Christ, dedicate himself to contemplation without denying himself active life. Behaving otherwise would not be right. Indeed, just as we must love God in contemplation, so we must love our neighbor with action. It is therefore impossible to live without the presence of both the one and the other form of life, nor can we live without experiencing both the one and the other” (Differentiarum, Book II, 34, 135).

Follow

Follow