The conversion of Rudolf Höss

José Maria C.S. André

Jonathan Glazer’s recent film, released on January 2024, which I haven’t seen, was the occasion for a friend to tell me the story of the central character, a monster called Rudolf Höss. Not to be confused with the well-known Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s right-hand man.

Rudolf Hoss was born into a German Catholic family, but soon became an atheist. During the First World War, he began working in a military hospital; then, at the age of 14, he joined the German army; at the age of 15, he fought in Iraq and Palestine, became a cavalry commander, was wounded several times and received high decorations. During this period, not far from there, the Armenian genocide and the Assyrian genocide were taking place. When the war ended, Höss returned to Germany to attend secondary school. He joined the Nazi party, went to prison for misdemeanour with murder and was released thanks to an amnesty.

With the seizure of power by the Nazi party, he began an abominable career. It’s hard to pick out examples. In charge of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, he ordered all prisoners who were not working to stand outdoors, poorly dressed, on a winter’s day with a temperature of minus 26 degrees Celsius. When someone tried to take some frozen people to the infirmary, he had the doors closed. Seventy-eight prisoners died during the day and 67 more at night.

Rudolf Höss’ best-known position was that of Head of the Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp. Every day, several trains arrived with thousands of prisoners each, to be killed. The killing was gradually perfected and, according to Rudolf Höss himself, the process was quite efficient, the limitation being the capacity of the gigantic furnaces that burned the bodies. Höss first calculated that 2.5 million people were killed at Auschwitz and another half a million died of starvation and disease; later, thinking about the capacity of the gas chambers, he thought that 1 to 2 million would be more realistic than 2.5 million. The very light-heartedness of these assessments is shocking.

The report of the psychologist who examined Höss at the time of his trial expresses just how far depravity had gone: “Höss is quite matter-of-fact and apathetic (…). There is too much apathy to leave any suggestion of remorse and even the prospect of hanging does not unduly stress him. One gets the general impression of a man who is intellectually normal, but with the schizoid apathy, insensitivity and lack of empathy that could hardly be more extreme in a frank psychotic.”

The element that changed such a hideous personality was the kindness with which the Polish jailers treated him. Höss expected revenge and, in the end…in a message to the prosecuting attorney, he wrote:

“My conscience compels me to make the following declaration. In the solitude of my prison cell, I have come to the bitter recognition that I have sinned gravely against humanity. (…) I was responsible for carrying out part of the cruel plans (…) for human destruction. In so doing I have inflicted terrible wounds on humanity. I caused unspeakable suffering for the Polish people in particular. (…) May the Lord God forgive one day what I have done. I ask the Polish people for forgiveness. In Polish prisons I experienced for the first time what human kindness is. Despite all that has happened I have experienced humane treatment which I could never have expected, and which has deeply shamed me. May the facts which are now coming out about the horrible crimes against humanity make the repetition of such cruel acts impossible for all time.”

A few days before his hanging, Höss converted to Catholicism. Father Władysław Lohn heard his confession and gave him Communion the next day.

In a farewell letter to his wife, Höss wrote:

“(…) I can see today clearly, severely and bitterly for me, that the entire ideology (…) in which I believed so firmly and unswervingly was based on completely wrong premises and had to absolutely collapse one day. And so my actions in the service of this ideology were completely wrong (…) My turning away from my belief in God was based on completely wrong premises. It was a hard struggle. But I have again found my faith in my God.”

He said goodbye to one of his sons, writing:

“Keep your heart good. (…) Let yourself be guided primarily by warmth and humanity. Learn to think and judge for yourself, responsibly. (…) The biggest mistake of my life was that I believed everything faithfully which came from the top, and I didn’t dare to have the least bit of doubt (…). In all your undertakings, don’t just let your mind speak, but listen above all to the voice in your heart.”

In this world, wounded once again by painful and senseless wars, it did me good to know this example of how signs of kindness bring about amazing cures.

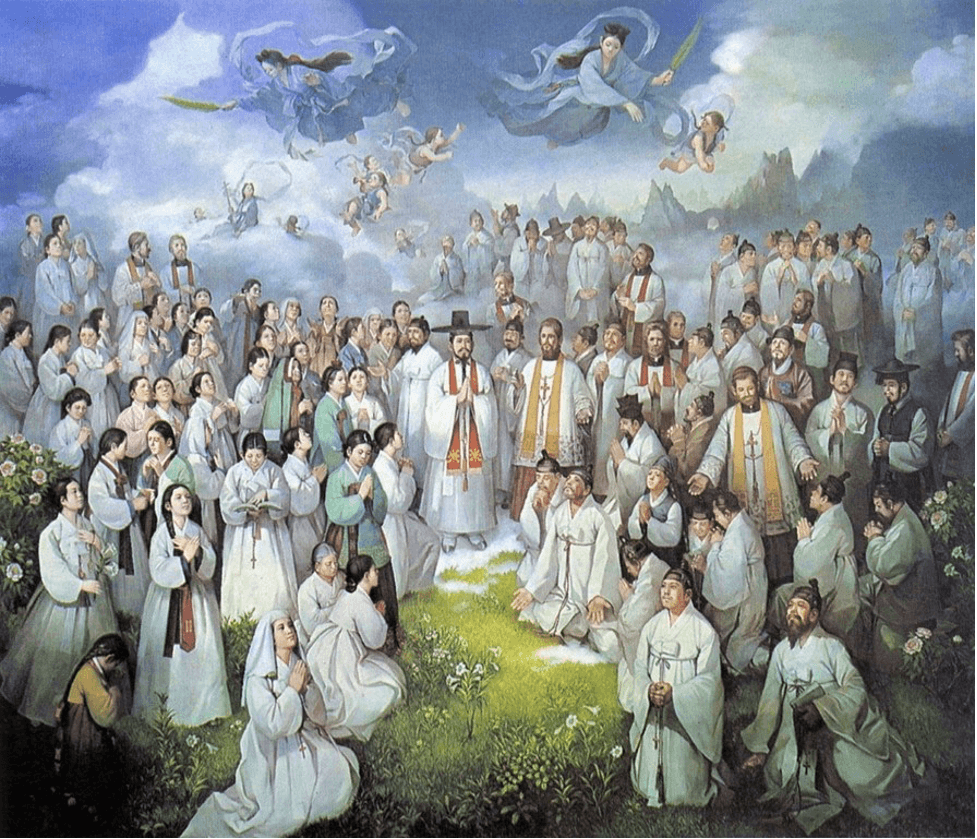

(Image caption: Rudolf Höss, in the front row right, on a visit by Heinrich Himmler to the Auschwitz death camp in 1942.)

Follow

Follow