Rev. José Mario O. Mandía

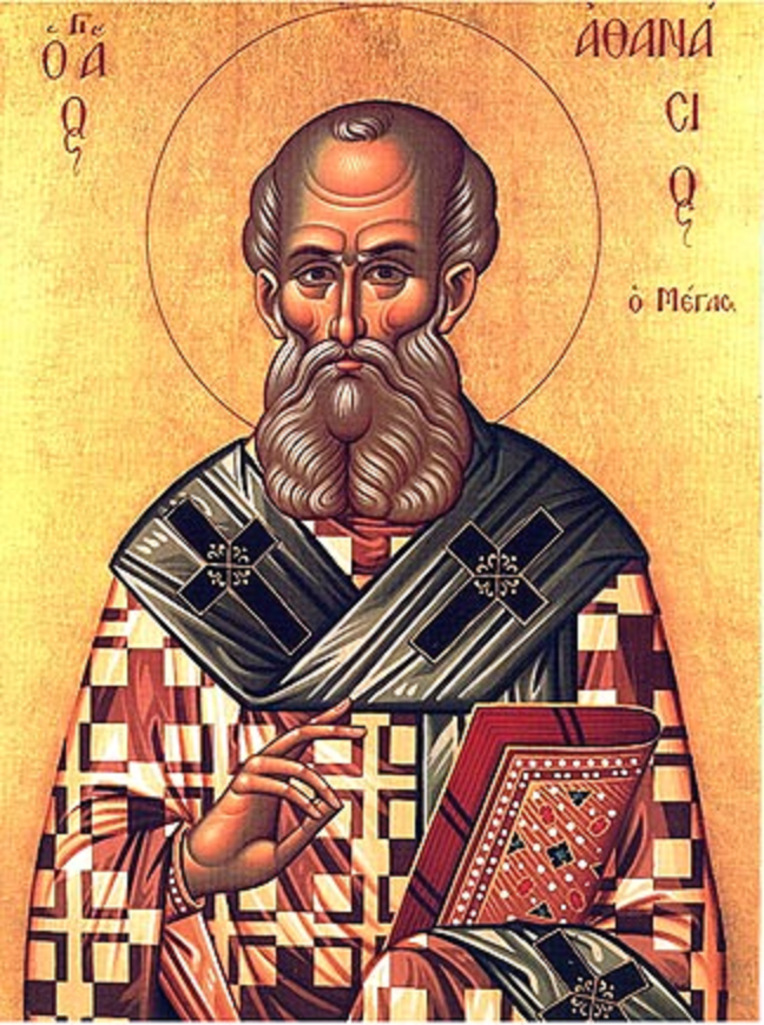

From Caesarea, let us go back to Alexandria. When Bishop Alexander (cf. Church Fathers, 22) died in 328 AD, he was succeeded by Athanasius who turned out to be the fiercest opponent of the Arian heresy (cf. Church Fathers, 22), an error which still appears today under different forms.

Pope Benedict XVI writes: “Athanasius was undoubtedly one of the most important and revered early Church Fathers. But this great Saint was above all the impassioned theologian of the Incarnation of the Logos, the Word of God who – as the Prologue of the fourth Gospel says – ‘became flesh and dwelt among us’ (John 1: 14)” (General Audience, 20 June 2007).

In his De Incarnatione, Athanasius wrote that the Word of God “was made man so that we might be made God; and he manifested himself through a body so that we might receive the idea of the unseen Father; and he endured the insolence of men that we might inherit immortality” (54, 3).

“The Greek Church would later call him ‘the Father of Orthodoxy’ whereas the Roman Church counts him among the four great Fathers of the East” (Quasten, III, p. 20).

“In all likelihood Athanasius was born in Alexandria, Egypt, in about the year 300 A.D. He received a good education before becoming a deacon and secretary to the Bishop of Alexandria, the great Egyptian metropolis. As a close collaborator of his Bishop, the young cleric took part with him in the Council of Nicaea, the first Ecumenical Council, convoked by the Emperor Constantine in May 325 AD to ensure Church unity” (Benedict XVI, General Audience, 20 June 2007).

Athanasius showed great courage even when his life was endangered. He defended the faith professed at Nicaea. This is why the Arians considered him as their key enemy. They managed to get the emperor and corrupt ecclesiastical authorities on their side. “Five times was he banished from his episcopal see and spent more than seventeen years in exile” (Quasten, III, 20). Despite his opposition to Arianism, he was tolerant and patient towards those who were misled by the false teaching.

The Arians won Emperor Constantine’s support because he (and later his son Constantius II) “was not so much concerned with theological truth but rather with the unity of the Empire and its political problems; he wished to politicize the faith, making it more accessible – in his opinion – to all his subjects throughout the Empire” (Benedict XVI, General Audience, 20 June 2007).

Even in exile, however, Athanasius was able to spread the correct doctrine. Moreover, he also brought with him the ideals of monastic life as lived by the great hermit, Saint Anthony (251-356), who was his close friend and is known as one of the Desert Fathers. Anthony is also known by other names: Anthony of Egypt, Anthony the Abbot, Anthony of the Desert, Anthony the Anchorite, Anthony the Hermit, and Anthony of Thebes. He is also regarded as the Father of All Monks.

When he returned for the last time in Alexandria, Athanasius spent his final years working to bring back peace and reorganize the Christian communities. He was able to continue writing and preaching on the theme of the Incarnation which he had defended all his life.

Pope Benedict says that “Athanasius also wrote meditational texts on the Psalms, subsequently circulated widely, and in particular, a work that constitutes the bestseller of early Christian literature: The Life of Anthony, that is, the biography of St Anthony Abbot. It was written shortly after this Saint’s death precisely while the exiled Bishop of Alexandria was staying with monks in the Egyptian desert” (General Audience, 20 June 2007). The book gained wide acceptance and inspired monastic life in the Eastern Church as well as in the Western Church.

On 2 May 373, Athanasius consecrated Peter II as successor to his office. On that day, he died peacefully, surrounded by his clergy and the faithful.

Follow

Follow