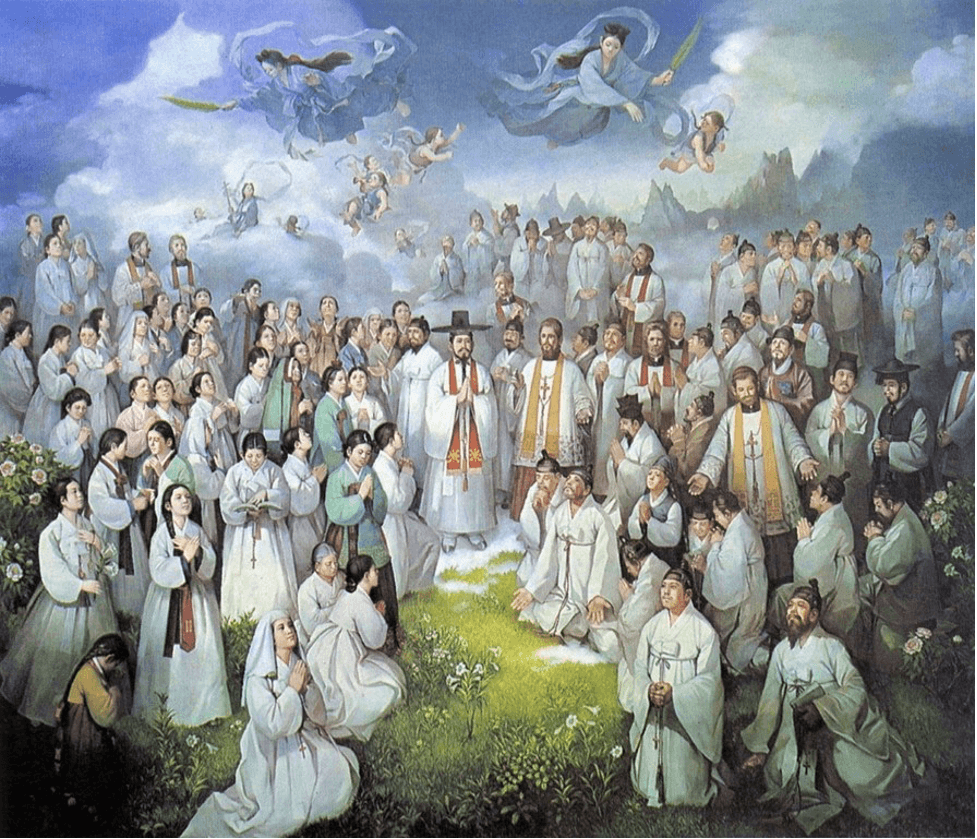

(Above) The Lighthouse – “A Place of Hope” is a Community Service Centre run by the Penang Office For Human Development, the social arm of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Penang | Photo courtesy: https://www.facebook.com/The-Lighthouse-155309407857742/

Joaquim Magalhães de Castro

Whenever Christianity is talked about in Malaysia and Malacca, the members of the thriving Portuguese-descendant community resident there, known locally as kristangs, come to the fore. However, the truth is that, all over the west coast of the Malay peninsula there are pockets of Catholics, the most relevant being that of Georgetown, on the Island of Penang, self-styled as Eurasian because, in addition to the Portuguese component, it also cultivates its Dutch, English, French and other origins.

Back in Penang, decades after my first visit, I look, as always, for signs of Luso-Asian interaction. And there is no better place for that than cemeteries. In the Protestant cemetery, which is open to all, with well-maintained grass, one of the plaques immortalizes the memory of one such “Fennella Loureiro, who died at the age of 30 in 1875”. Bordered by half walls, the Catholic cemetery is closed to visitors. Someone I met there suggests I look for the key on the other side of the long, mossy wall.

The land adjacent to the Church of São Pedro is where the Lighthouse Thrift House operates. It is a Christian organization that supports the most needy with the help of volunteers and donations, and also derives funds from its own bakery. At the entrance, I come across a tall man with a brimmed hat, clear Caucasian features and an initially suspicious face that gradually opens up. James Noronha, born and raised in Penang and with family members in Kuala Lumpur and Australia, has no doubts as to where his surname came from. After “some investigation”, he came to the conclusion that he was descended from a certain captain of a ship during the height of maritime discoveries; or perhaps even a viceroy of Estado da India (Portuguese India). A noble family then? “Of course,” says James, “you were lucky enough to come across a Eurasian of Portuguese origin.” Nothing is remembered of the Portuguese language that once flourished in that region, and now, at 72 years of age, he works as an official doorman at the institution that presents itself as a “place of hope”, not only for the economically disadvantaged, but also for the many drug-addicted rickshaw drivers.

A septuagenarian who looks like he is in his fifties (not a single wrinkle on his face!), James is one of the only Portuguese descendants left. The older ones died and the younger ones emigrated, leaving only a few families, very few. His family members living in Australia are dedicated to business, as are most Asians. “Only with honest work you can’t make enough money,” comments my interlocutor. But immediately afterwards, philosophically fatalistic, he concludes: “But if we don’t work, we die.”

James Noronha hates to travel, and even Malacca seems far away to him, let alone Australia where he has his sisters and where his recently deceased wife lived for a few years. “I live in stone and lime in Penang, and here I enjoy life,” he asserts. This aversion is certainly not unrelated to the fear of flying, despite the fact that in his youth he worked as a civil servant at the British Australia Air Base.

Our conversation is interrupted by the arrival of two ladies of Chinese ethnicity, devout members of the Lighthouse Thrift House group, who bring food products to distribute to the most vulnerable. James helps them find a place to park their car. “There is a kind of canteen here and the help provided by parishioners is essential,” comments one of them. “We have a very firm foundation, and we are always ready to take care of the homeless, orphans, addicts, in short, of all of humanity that most consider lost.”

Meanwhile, we pass by the Church of San Francisco de Xavier, dedicated to the local Catholics who speak Tamil, with a beautiful and stately building right next door where an orphanage and a home for the elderly are located. At the secretariat, Noronha says, “You are lucky because the lady who is working here knows me well.” I get the key that gives me access to the cemetery, which is, after all, the main reason for my visit.

On the walls and ceiling of that room are obvious signs of the predominance of the Chinese ethnicity among the local Catholic community. The false panchões and the red lanterns on the ceiling, placed at the time of the Lunar New Year still remain despite the fact that summer is already well advanced.

As for the sacred space itself (as the cemeteries here are called), tombstones, mostly engraved in English, perpetuate the names of “Helena Louisa D’Reys, who died on August 24, 1888, only one month and eighteen days old”; and “Paschal de Silva, who left this life on May 5, 1805”. Other names that appear are Marcillina Simoens, Anastasia Catherina de Souza, W.W.W de Oliveiro, Michael D Souza, Perte Patrick Pereira and Peter Benson Pereira. In a more remote corner, in a pinkish marble, I come across the following inscription, almost erased: “Grasinha Gracia, born in Bengal, died Thursday, at 11 o’clock in the evening of October 5, 1825, at the age of 70.”

Follow

Follow