Rev José Mario O Mandía

jmom.honlam.org

Making choices implies knowing the options before us.

When a person goes to a restaurant, he first checks the menu to see what he can order, or asks the waiter what they serve.

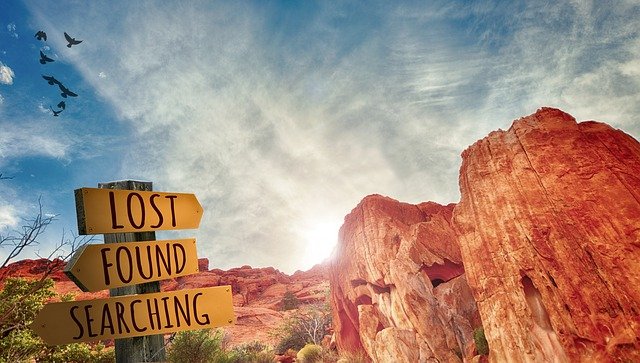

When a person finds himself in an unfamiliar city, he first consults the map, checks the road signs, asks the policeman, so he does not get lost and reaches his destination.

The moral life requires an objective reference point. That reference point is called “law.”

“In no way does [a traveler] consider that his freedom is being restricted, nor does he consider it a humiliation to have to depend on maps, signposts, or guides to get where he is going. If he is unsure, or begins to feel lost, the signposts he meets are for him an occasion of reassurance and relief.

“In fact, very often we rely more on maps or signposts than on our own sense of direction, of whose unworthiness we have plenty of experience. When we follow the signposts we don’t have any sense of being imposed upon; rather do we welcome them as a great help, a fresh piece of information which we immediately proceed to make our own” (Francis Fernández, In Conversation with God, vol 4, pp 451-452).

The CCC (No. 1951) defines “law” as “a rule of conduct enacted by competent authority for the sake of the common good. The moral law presupposes the rational order, established among creatures for their good and to serve their final end, by the power, wisdom, and goodness of the Creator.”

We find three elements in this definition.

(1) It is a rule of conduct which presupposes the rational order. Law is not irrational; it is not something given out of pure whim. Law proceeds from reason (not from the will or pure arbitrariness), and is addressed to the reason or intellect of man.

St Thomas explains: “Law is a rule and measure of acts, whereby man is induced to act or is restrained from acting: for “lex” (law) is derived from “ligare” (to bind), because it binds one to act. Now the rule and measure of human acts is the reason, which is the first principle of human acts” (Summa Theologiae, I-II q90 a1).

(2) It is enacted by competent authority. Not just anyone can draw up a law. The authority, who is charged with safeguarding and promoting the common good, has to enact and promulgate it.

(3) It is given for the sake of the common good. Reason guides man to work not only for the individual good, but for the good of everyone. Moreover, the power that authority has is directed to the common good. Hence, the laws it enacts should have the common good in mind. Note that the term “common good” does not only refer to the sum of all material goods. Indeed, the highest common good of man and the universe is God himself.

The law is an ordinance that emanates from reason and thus announces the truth. In this way, it “feeds” man’s freedom so that man can make intelligent choices. The law gives facts about life, not arbitrary rules with arbitrary rewards and punishments. Just as road signs are not borne of caprice, but from the need to indicate the truth about which roads lead where.

CS Lewis, in his Reflections on the Psalms (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1986, p 61) wrote, “A modern logician would say that the Law is a command and that to call a command ‘true’ makes no sense. ‘The door is shut’ may be true or false but ‘Shut the door’ can’t. But I think we all see pretty well what the Psalmists mean. They mean that in the Law you find the ‘real’ or ‘correct’ or stable, well-grounded directions for living. The law answers the question ‘How can a young man keep his way pure?’ (Psalm 119:9). It is like a lamp, a guide (Psalm 119:105). There are many rival directions for living, as the Pagan cultures all round us show. When the poets call the directions or ‘rulings’ of Yahweh ‘true’ they are expressing the assurance that these, and not those others, are the ‘real’ or unassailable ones; that they are based on the very nature of things and the very nature of God.”

Lewis adds, “There were in the eighteenth century terrible theologians who held that ‘God did not command certain things because they are right, but certain things are right because God commanded them.’ To make the position perfectly clear, one of them even said that though God has, as it happens, commanded us to love Him and one another, He might equally well have commanded us to hate Him and one another, and hatred would then have been right. It was apparently a mere toss-up which He decided on. Such a view of course makes God a mere arbitrary tyrant.”

No wonder, then, that Pope John Paul II entitled the Encyclical Letter on the Church’s moral doctrine Veritatis Splendor – the Splendor of Truth.

(Photo: JanBaby at Pixabay)

Follow

Follow