Fr Paolo Consonni, MCCJ

After more than a month into the war in Ukraine, we have already gotten used to images of houses destroyed, long lines of refugees, columns of smoke after bombardments, burned-out tanks and, sadly, hundreds of wounded people and dead bodies. We are so overexposed to this kind of news that we risk becoming immune to horror. For young people it is even worse – war is a virtual reality that can be treated like a videogame. The banality of evil causes us to become inured to it.

Famous author Hannah Arendt, in a controversial book about the motivations of prominent Nazi leader Adolf Eichmann, responsible for the killing of millions of Jews during the Second World War, used the term “the banality of evil”. She realized that many of those who committed those crimes were neither perverted nor sadistic monsters, but “terrifyingly normal” people, acting out of a sense of duty, to advance their career, make money or even simply to blindly carry out orders as diligent bureaucrats. History shows that an accumulation of small choices made for banal motivations, without thoroughly thinking of their consequences, can provoke tragedies of unimaginable proportions.

This Sunday, which marks the beginning of Holy Week, we will listen once again to the narration of the Lord’s Passion (Lk 22:14—23:56). Will we pay attention, or we will hear it as the same sad story of violence and death, similar to many others in the news? Will we view the evil in the events leading to Jesus’ death dispassionately because of their banality? There is nothing demonstrably alarming about Jesus’ Passion. It is a story of jealousy, greed, fear of someone upsetting the status quo, powerful people getting rid of a troublemaker through a corrupted justice system, zealous people trying to defend the purity of their traditions… we see these things happening every day all over the world.

Besides, the narration of the Passion in each of the four Gospels is very sober. While Jesus’ sufferings are well described, there is no emphasis on the tortures, blood and all the gore that makes a horror movie or a videogame morbidly exciting. The point of the description of the Passion in the Gospels is not to make the death of Jesus, the Son of God, appear more painful than others (pain cannot be compared!), but to show its significance as the conclusion of Jesus’ extraordinary life.

The life of Jesus was one of total self-giving, a gift given to the world by the Father who sent Him. A life in which He “went about doing good and healing all who were oppressed by the devil, for God was with him” (Acts 10:38). A life in which He carried upon His body all the darkness and tragedy of human experience, especially the ones coming from evil and death, only to return compassion, mercy and forgiveness. A life of unconditional love.

We might become indifferent toward evil owing to its banality, but our hearts long to find something, or better still, someone, to save us from the cynical routine in which our lives become stuck. Something – or someone – that can embrace our struggles, our failures and our limitations. Something or someone to whom we can entrust our last breath, saying: “Into your hands I commend my spirit.” In other words, we long for the unconditional love Jesus’ revealed throughout His whole life and death.

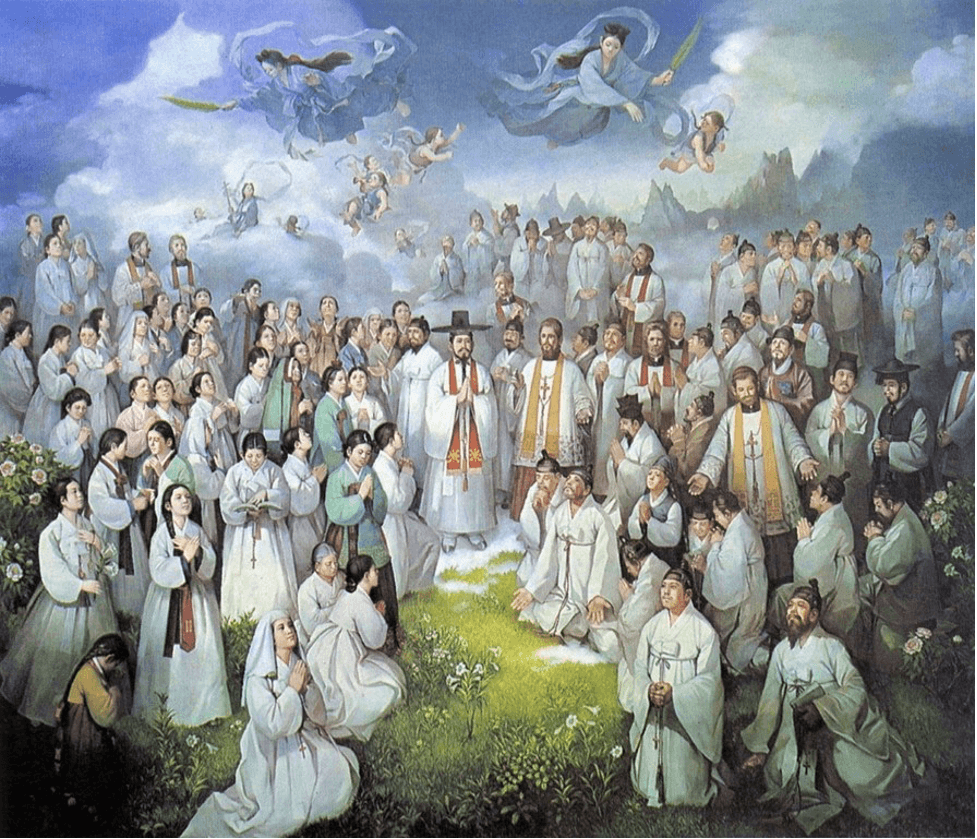

The early Christians understood that the narration of Christ’s Passion and death was important not only because it was expiation for our sins, but also because they understood that it was worth living and dying like Him. They also realized that only by inserting their own lives and deaths into His life and death, their existence might also become meaningful, worth living, worth the pain.

Christ’s death saves us not only from the eschatological Hell, but also from a hellish, dull existence and relational life.

Jesus’ disciples of every time and place, no matter whether married or not, all the young people who left everything to follow in the footsteps of St. Francis of Assisi, St. Ignatius of Loyola or Mother Teresa of Calcutta (among many), all made this choice in their ordinary lives with an extraordinary sense of gratitude for having found what matched their hearts’ desire to live a meaningful life. They answered the unconditional love they received from Christ with the gift of their lives. Only this love can overcome the inexorable passing of time, the cruelty of the world, the banality of evil, the weariness caused by sickness and the inevitability of the tomb.

Jesus’ Passion and Death is not simply another story of pain and death. It is the only one which can bring light and meaning to all the others, including yours. Listen to it, once again, like the first Christians did, with an overwhelmed and grateful heart.

Follow

Follow