Aurelio Porfiri

A few weeks ago, on March 5, we commemorated the 100th anniversary of the birth of Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922-1975), one of the leading intellectuals of the left; poet, writer, movie director and polemicist. He also wrote and directed the award-winning film (The Gospel According to St. Matthew), on the life of Jesus, which fascinated him. His movie, which is directly based on the Gospel of Matthew, is considered by some critics as the best representation of the life of Jesus. While I do not wish to offer my own opinion on the subject, one cannot deny that the movie certainly had a strong impact on viewers.

To say that Pasolini was a controversial figure is an understatement. His conduct in the moral sphere was such that it would have spelt a death knell for any non-leftist intellectual.

Yet it cannot be denied that he had certain values, and his interest in tradition was unlike that of the other intellectuals of his political sphere.

What contributed to his fame, unfortunately for him, was his ghastly end, a horrific murder that has yet to be solved. It is a death I remember quite well, despite my young age at the time. The brutal killing made headlines for a long time and was under investigation for ages.

The philosopher Marcello Veneziani in his book Imperdonabili offers this appreciation of Pasolini: “Pier Paolo Pasolini is one of those authors loved not for what he wrote but for what he represented. It is not his works and his films that build the myth of him, but his life, his death and his anger as a wounded and cursed prophet. You can love Pasolini for opposite reasons: poet of transgression or poet of tradition, communist militant and progressive intellectual or reactionary populist writer, in his way, also religious. “Italy today is destroyed, exactly like Italy in 1945. Indeed, the destruction is certainly even more serious, because we are not among the rubble, albeit excruciating, of houses and monuments, but among ‘rubble of values’: humanistic values and, what is worse, popular values. Do not be afraid of the sacredness and sentiments of which consumerist secularism has deprived men, transforming them into brute and stupid fetish-worshiping automatons.”

Pasolini represented Italy’s critical conscience against the devastating effects of consumerism, homologation, political, social and environmental corruption, violence of all kinds, including progressivism and false respectability. He was a religious seeker of the archaic, peasant soul of the people, the defender of all diversity and marginalization. For heaven’s sake, Pasolini was Pasolini, a heretical Marxist, anti-modern communist, rural populist and blasphemous religious; the opposite of devoted atheists, so to speak.” This reading of Veneziani, from the right, has always seemed very interesting to me, because it highlights the profound contradiction that is at the root of the understanding of an author who, while referring to an anti-traditional ideology such as the Marxist one, cannot fail to indicate in the loss of tradition a great modern tragedy.

We think of his desperate search for authenticity, almost of a pictorial type, that search which made him afford opportunities to unknown actors taken from the street, like Ninetto Davoli and Franco Citti, who was the protagonist of one of his most celebrated films Accattone of 1961. Yet, he seems to be able to do without the truth, a truth he seeks where he cannot find it. But all this is at the heart of the contradiction he represented, which made him speak of New York in the language of a revolutionary poet: “It is a magical, overwhelming, beautiful city. One of those lucky cities that have grace. Like certain poets who every time they write a verse make a beautiful poem. I’m sorry I didn’t come here much earlier, twenty or thirty years ago, to stay there. It had never happened to me to fall in love with a country like this. Except in Africa, perhaps. But Africa is like a drug you take so as not to kill yourself, an escape. New York is not an escape: it is a commitment, a war. It puts in you the desire to do, to face, to change: you like the things you like, that’s it, at twenty. I did not feel a stranger, I immediately learned to wander the streets even as I was born there: yet I recognized her. Young people have fabulous taste – see how they are dressed. In the most sincere, most unconventional way possible. They don’t care about petty-bourgeois or popular rules. Those flashy sweaters, those cheap jackets, those incredible colors. And so they leave, proud, aware of their elegance which is never a mythical or naive elegance. This is the most beautiful thing I have seen in my life. This is one thing I will not forget as long as I live. I have to go back, I have to stay here even though I am no longer eighteen. How sorry I am to leave, I feel robbed. I feel like a child in front of a cake to eat, a cake of many layers, and the child does not know which layer he will like best, he only knows that he wants, that he has to eat them all. One by one. And just as he is about to bite into the cake, they take it away from him. I wish I was eighteen to live a whole life down here”.

Then, on the other hand, praise the resistance to modernity: “I know this: that the Neapolitans today are a great tribe that instead of living in the desert or savanna, like the Tuareg and the Beja, lives in the belly of a large seaside city. This tribe has decided – as such, without being responsible for its own possible forced mutations – to become extinct, rejecting the new power, that is, what we call history or otherwise modernity. The Tuareg do the same thing in the desert or the Beja in the savanna (or even the gypsies have been doing it for centuries): it is a refusal that has arisen from the heart of the community […]; a fatal denial against which there is nothing to be done. It gives a deep melancholy like all tragedies that are done slowly; but also a profound consolation, because this refusal, this denial of history, is right, it is sacrosanct”.

In short, it was a profound contradiction, perhaps even for himself.

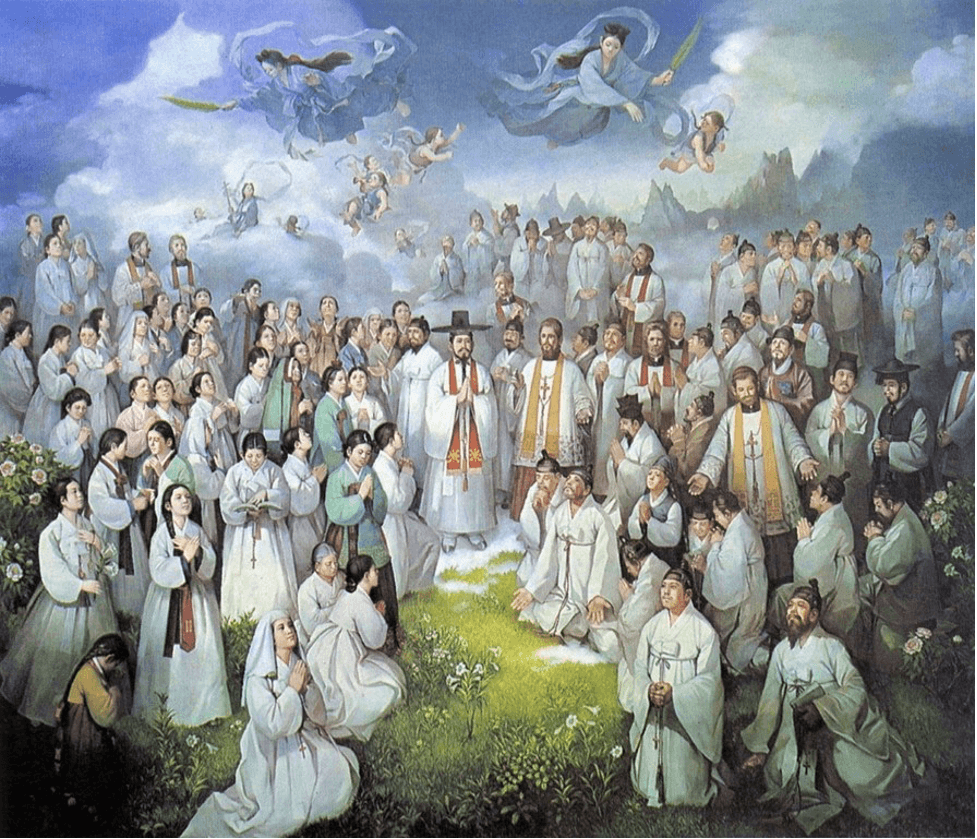

(Photo: djedj at Pixabay)

Follow

Follow