– Marco Carvalho

The University of Saint Joseph hosted last week the first of a series of lectures about the importance of the human factor in social services. The initiative, promoted by the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Saint Joseph, aims to provide social workers in the territory with the opportunity to deepen their knowledge and their understanding of the other. The first conference, organized in partnership with Caritas, was centered in the relationship between spirituality, religion and social service. Vítor Teixeira, Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Saint Joseph, explains how spirituality makes a difference.

How do spirituality, religion and social work go hand in hand? In a society like Macau’s society, where much of the social work falls under the responsibility of Catholic-inspired organizations, is this connection a key point of differentiation or not? How does the service provided by these institutions differ from the service provided by governmental or secular entities? Is there anything that differentiates the care being provided by church-related institutions from the care provided by governmental institutions, for example?

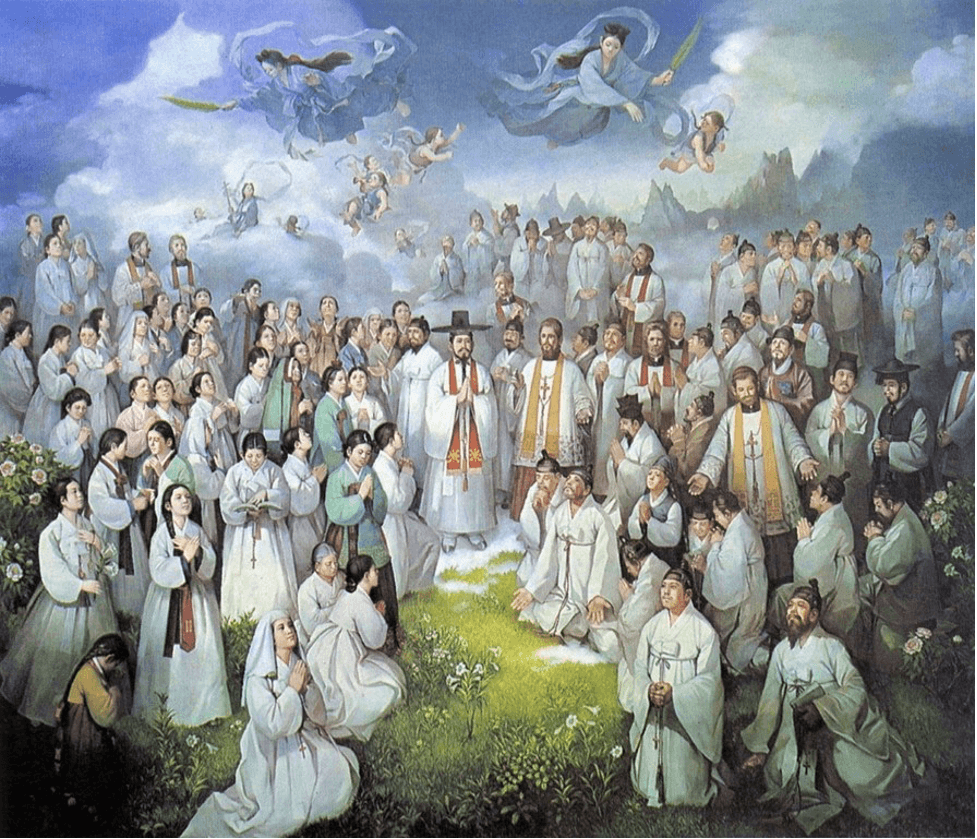

What was argued on the conference was that, in fact, spirituality is part of what makes us human, what makes us people. We live in a society that has its own, specific ways of living spirituality. The Catholic Church has been in Macau, as we all know, for many years now and has implemented and fostered its way of living spirituality.

One thing is evangelization as it is seen by a religion. When we talk about evangelizing as a religious mission or achievement, we are talking about a narrative that this religion brings to the people and which is imbued with the culture and history of that religion. Nevertheless, one needs to go beyond that and spirituality is an individual phenomenon for each and every one of us. But it is also universal. Thus, it makes sense that when introducing spirituality, one opts for fostering what some authors call “hidden or invisible religion”; that implies to venture on mission, principles and values. It is in the mission, principles and values of the organization itself that this idea of spirituality should be included and not so much in the direct explanation of the history of Jesus Christ or the Buddha or, otherwise, by applying the rituals and the beliefs of a particular religion. Instead, what makes a difference is to permeate a concrete practice with the values and the beliefs that underlie that given religion. If this is done, what we will see is that we find more aspects in common than aspects that differentiate us among seemingly different religions. This is what really moves us: regardless of religion, to bring spirituality into social intervention can be very important. This is a practice that has been used in hospitals with terminally ill patients who need faith and hope, that need to find meaning in life. It is an important practice in education, when one tries to convey principles and ethical and moral values. And it’s also important in counseling and psychotherapy – and these were two aspects that we addressed at the conference – because we often have people who bring feelings of guilt, who bring us feelings of uneasiness, precisely because of their associated religious issues. Spirituality and religion can, nevertheless, give hope, they can make life meaningful and if people really believe in a particular frame of values, it would be unwise not to use this framework for their own benefit in a therapeutic process.

Can this spiritual dimension have an ethical or moral influence in the way care itself is administered? My question is somewhat pernicious. In some European nations there’s a huge discussion about the legalization of euthanasia. It’s unthinkable for an organization such as Caritas – or other Catholic-inspired organizations – to consider euthanasia as a hypothesis…

When we speak of spirituality and morality we are, essentially, evoking that image of the “good little angel” and the “bad little angel,” one in each side of our head, this eternal conflict that human beings are confronted with, having to decide between what is right and what is not. This is the basis of morality. More than being right or not – this is a perspective that varies from religion to religion – what is universal is our ability to decide. It is our ability to choose that Catholicism speaks of, our free will. This capacity to decide, to make decisions is essential in life. If we are going to imbue the practice of an organization with ethical and moral principles that are related to a certain religious culture, I should obviously expect that in an organization that shares these values based on Catholicism, euthanasia would not fit. It’s interesting, because even in psychotherapeutic terms, we can… In this conference I had the opportunity to talk about Victor Frankl, who was a Jewish psychiatrist. He lived at the time of the Holocaust, the Nazis arrested him and he lived for many years in a concentration camp. He saw people dying, he saw people committing suicide and he explained that even in the darkest situations it is possible to find meaning in life. When we address cases of terminal illness, the role of a counselor who believes in the principle of the inalienable value of life, should be helping these people to find reasons to live, rather than to enable those people so that they can end their lives. In philosophical terms, Albert Camus addresses precisely this in The Stranger: “What reasons do I have to stay alive?” In fact, this is absolutely spiritual and existential. And that is the reason why in some countries – or in most of the places where euthanasia is accepted – most of them do not accept it without first having a psychotherapeutic intervention. The main objective of that intervention is to understand to what extent that person is aware that this is really the solution that he wants. On the other hand, it aims to realize if it is possible or not to find meaning for life as an alternative to no life at all, which is what these people seek.

In places like Portugal, there are institutions – especially those linked to the Church – where – in addition to what is commonly done in nursing homes or day care centers – the rosary is also said, for example. Praying does help or not?

Yes. There are several studies that tell us that when people have faith, praying helps as long as people believe in those prayers. There are also several studies that show that to take part in rituals – even when one does not fully understand the meaning of these rituals – also helps to promote a sense of belonging. This happens a lot in Macau, in our local Catholic schools, where there is the Morning Prayer ritual, where there’s a reflection after lunch. Most of the kids who attend these schools are Chinese and they don’t really care for the meaning of these rituals. There are, nevertheless, several studies showing that the ritual itself is positive: it gives security and predictability to our existence. There is a British sociologist, Anthony Giddens, who talks a lot about this. Our life is made of cycles and rituals offer us stability, structure and visibility. They provide us with existential security. Praying, in it self, is good and will do even better if people have faith in what they are doing. It doesn’t hurt anyone, does it?

Follow

Follow