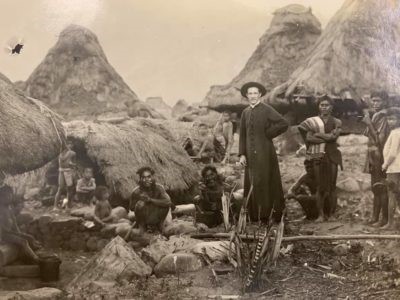

CICM Fathers. Used with permission.

– Fr Leonard E. Dollentas

In the previous article, we traced the gradual struggle of the Philippine Church towards having its own local bishops and native clergy to lead the parishes. In 1919 Maximum Illud came at the right time when transformation in the church was taking place. Through its inspiring light, the training and preparation of the Filipino clergy was intensified, parishes slowly been handed to the Filipino diocesan priests who, as Pope Benedict XV affirmed in Maximum Illud “… lies the greatest hope of the new churches. For the local priest, one with his people by birth, by nature, by his sympathies and his aspirations, is remarkably effective in appealing to their mentality and thus attracting them to the Faith. Far better than anyone else he knows the kind of argument they will listen to, and as a result, he often has easy access to places where a foreign priest would not be tolerated” (14).

The Period after the Spanish Regime

From 1521, the Philippine Church had journeyed that long with constant struggle. At the outset of the twentieth century when it was freed from Spanish domination, a new superior power emerged, the American regime. It was a journey that witnessed her growth through the succeeding years with the grace of God enfolding.

The Jesuit historian Fr Jose Arcilla related that when the Americans conquered the Philippines in 1900, the population was estimated at 7.6 million, of whom 6.9 million were listed as “civilized Christians.” The rest were what is called today “the cultural minorities.” At that time, there was only one city – Manila – and of the 7,642 islands comprising the archipelago, only 342 were inhabited.

Legacy of the Americans

The Philippines was under the Americans from 1898 to 1946. After the victory of the war against Spain, the American soldiers were tasked to build classrooms and were assigned as teachers of the Filipinos. In 1901 groups of volunteer teachers arrived aboard the USS Thomas and the soldiers yielded the teaching tasks to them. The Thomasites started what would be one of the contributions of America to the Philippine society, the public school system. Therefore, education became an imperative concern for the United States colonial government, since it is a vital channel to spread their cultural values, particularly the English language. Several schools were founded, including schools to train Filipino teachers. Although Spanish was still spoken, English was introduced as the medium of instruction.

Recalling the influence of the Spanish and American civilizations, Paul Monroe, on his 1912-1913 report on the condition of education in the Philippines wrote: “As the Church was the symbol of the Spanish rule, so the school has been the symbol of American civilization.”

The Catholic Church

Fr John N Schumacher SJ, another historian, described the church in the Philippines in the late 1900. He narrated that the situation of the Church during the early years of American rule was in total disaster. Church buildings and other church institutions were razed to the ground while others were severely damaged. He also described the number of the Filipino clergy to be fewer than six hundred seventy-five.

The anticlerical sentiment, which was directed at the Friars and members of the religious orders, was apparent in the growing Masonic Movement. It was intensified by a strong anti-Catholic bias and influenced many political leaders and educators. The Americans abolished the fortified unity of Church and State, which existed during the Spanish period. The consequence was distressing for the clergy: they could no longer engage in government functions and were left almost without financial resources. They lost control over the school systems as public schools were duly established and controlled by the Americans. The public school system excluded religious instructions from the academic program and this became a concern of the faithful who professed the faith.

Fr Jose S Arcilla SJ provided the records on how it was solved: since the Treaty of Paris provided that Filipino customs and traditions be respected, a compromise solution was approved, thus allowing religion to be taught to children whose parents asked for it, thrice weekly, and outside class hours.

The Protestant Missionaries

As early as 1898 the American Protestant Missionaries tried to smuggle bibles and promote mission works in the country. The Patronato then was still in effect and it had a strong prohibition against other religions, and prescribed that only the Catholic faith should prevail in the colony. Therefore, when the Americans came into power, Protestants missionaries rushed to “Christianize” the Filipinos. This confusing Protestant scheme can be understood from the fact that Protestant missionaries considered Latin Catholicism unchristian. Along with the American educators were Protestant evangelizers who came to establish their churches in the country. Protestantism spread largely in the public schools with the support of the American teachers, who were mostly Protestants themselves. Consequently, the American influence through education introduced a new faith orientation. Filipinos did not find this difficult to adjust to since they wanted to unload heavy Spanish influences anyway.

The various Protestant missions assigned the islands into regions of their evangelizing influence. Missionaries learned the local languages and began translating Protestant texts including the Bible. The Protestants were swift to attack the moral fiber of Filipino Catholics, they provided an alternative community to counter a people who lived in gambling, womanizing, dancing and drinking. There was a strong certainty that they were not fully Christians until they became Protestant; they had to be immersed in water to purify them of sinfulness and vices. Thus, the rise of Protestantism became a crucial concern for the Philippine Catholic Church to strengthen its doctrinal teachings and particularly emphasize Christian living.

New groups of Catholic Missionaries

To intensify the Catholic missions, new groups of missionaries who do not belong to Mendicant Orders, arrived in the country. The bishops, who were mostly Americans, strove to respond to the rising influence of Protestantism in the country. In 1905, the Irish Redemptorists arrived in the Philippines. The Dutch Mill Hill Missionaries followed after a year in 1906, then the Belgian C.I.C.M. or Scheut Missionaries in 1907. Another group of Dutch missionaries, the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart arrived in the country in the same year as the German members of the SVD or Divine Word Fathers in 1908. Most of these new missionaries helped in the formation of the Filipino clergy and augmented the ministry to the diocesan seminaries. The new missionaries intensified some new approach to evangelized the Philippine Church.

In 1921 the first batch of American Jesuits came. Their work in education, retreats, research and scholarship, social involvement, and mission work provided more impetus to the Church’s apostolic activity. By the second half of the 1920s the situation of the Church was showing signs of revival and empowerment to the local clergy. Members of the Aglipayan Church returned to the Catholic Church in large numbers; Catholic education grew both in numbers and in its standard of excellence. To give tribute to the efforts of the clergy and the religious, the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) declared the Year of the Clergy and the Religious from December 03, 2017 to November 25, 2018. This was part of the preparation of the Church in the Philippines for March 16, 2021, 5th centenary of the coming of Christianity to the Philippines.

Follow

Follow