PROV 8:22-31; ROM 5:1-5; JN 16:12-15

– Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI)

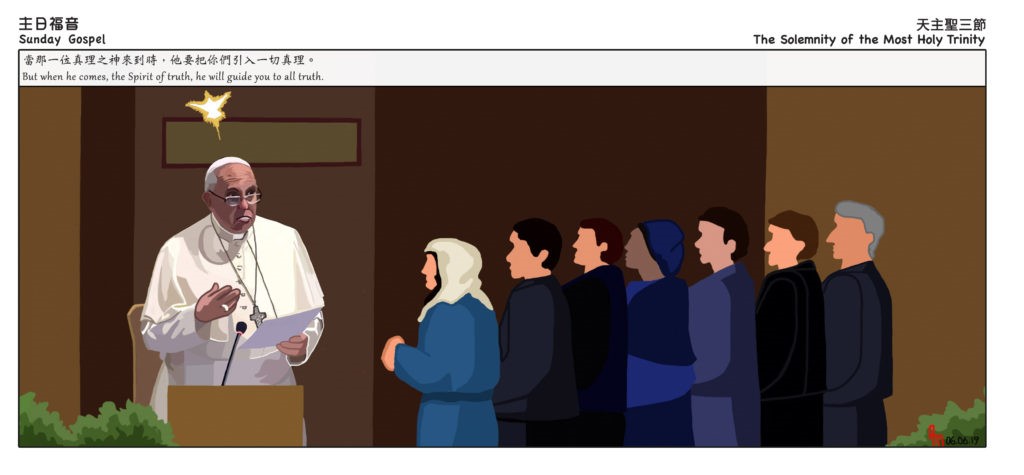

The feast of the Holy Trinity is different from all the other feasts of the liturgical year, such as Christmas, Epiphany, Easter, and Pentecost, when we celebrate the wondrous works of God in history: the Incarnation, the Resurrection, the Descent of the Holy Spirit, and consequently the birth of the Church. Today we are not celebrating an event in which “something” of God is made visible; rather, we are celebrating the very mystery of God. We rejoice in God, in the fact that he is the way he is; we thank him for existing; we are grateful that he is what he is and that we can know him and love him and that he knows and loves us and reveals himself to us.

But the existence of God, his being, the fact that he knows us–is that really a cause for joy? Certainly it is not something easy to understand or experience. Many gods in the different religions of peoples throughout the world are terrible, cruel, selfish, an inscrutable mixture of good and evil. The ancient world was characterized by a fear of the gods and a dread of their mysterious power: it was necessary to win the favor of the gods, to act in such a way as to avoid their whims or their bad humor. Part of the Christian mission was a liberating force that was able to drive out a whole world of idols and gods that are now considered empty, illusory appearances. At the same time it proclaimed the God who, in Jesus, became man, the God who is Love and Reason. This God is mightier than all the dark powers that the world can contain: “We know that ‘an idol has no real existence,’ and that ‘there is no God but one.’ For although there may be so-called gods in heaven or on earth-as indeed there are many ‘gods’ and many ‘lords’–yet for us there is one God, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we exist” (1 Cor 8:4-6).

Even today this is a revolutionary, liberating message with respect to all the ancient traditional religions: No longer is there reason to fear the spirits that surround us on all sides, coming and going ceaselessly, eluding our vain efforts at exorcism. Anyone who “dwells in the shelter of the Most High, who abides in the shadow of the Almighty” (Ps 91:1) knows that he is safe, guarded tenderly by the One who welcomes him and offers him refuge. Someone who knows the God of Jesus Christ knows that the other forms of fear in the presence of God have disappeared also, that he has overcome all the forms of harrowing existential anguish that spread through the world in ever new ways.

In view of all the horrors of the world, the same question unceasingly arises: Does God exist? And if he exists, is he truly good? Might he not be instead a mysterious and dangerous reality? In modern times this question is posed differently: the existence of God seems to be a limit to our freedom. He is perceived as a sort of supervisor who pursues us with his glance. In the modern era, the rebellion against God assumes the form of a fear of an omnipresent, all-seeing God. His glance appears as a threat to us; indeed, we prefer not to be seen; we just want to be ourselves and nothing more. Man does not feel free, he does not feel that he is truly himself, until God is set aside. The story of Adam already notes this: he sees God as a competitor. Adam wants to lead his own life, all alone, and tries to hide from God “among the trees of the garden” (Gen 3:8). Sartre, too, declared that we must deny God, even if he must exist philosophically, because the concept of God is opposed to man’s freedom and greatness.

But has the world really become brighter, freer, happier after setting God aside? Or has man not been stripped of his own dignity and condemned to an empty freedom that makes cruel and ruthless choices of all sorts? God’s glance frightens us only if we think of him as reducing us to some kind of servitude or slavery; but if we read in it the expression of his love, we discover that he is the fundamental requirement for our very being, that it is he who makes us live. “He who has seen me has seen the Father”, Jesus said to Philip and to us all (Jn 14:9). Jesus’ face is the face of God himself this is what God is like. Jesus suffered for us, and by his death he has given us peace; he reveals to us who God is. His glance, far from being a threat, is a glance that saves us.

Yes, we can rejoice that God exists, that he has revealed himself to mankind, and that he does not leave us alone. How consoling it is to know the telephone number of a friend, to know good people who love us, who are always available and never aloof: at any time we can call them and they can call us. This is precisely what the Incarnation of God in Christ says to us: God has written our names and phone numbers in his address book! He is always listening; we do not need money or technology to call him. Thanks to baptism and confirmation, we are privileged to belong to his family. He is always ready to welcome us: “Behold, I am with you always, to the close of the age” (Mt 28:20).

(Homily given in the Cathedral of Bayeux on the Feast of the Holy Trinity, June 6, 2004,when he represented Pope John Paul II at the 60th anniversary celebration of D-Day.)

Follow

Follow