– Vittorio Messori

If I will be granted mercy to access the Paradise – of course, after an adequate “fee” to pay for the inconsistency between what I believed and how I lived – I will ask the great Custos, St Peter, to know and embrace a lady, Marie Beauzac, who died under the guillotine in the illustrious Marian city of Le Puy-en-Velay. A place that is dear to me not only for its singular beauty, but also because it is strictly, and mysteriously, linked to the destiny of Lourdes on which the Virgin venerated at Le Puy depended for centuries.

Why want to track down that madame Marie unknown to historians and only known by some local scholar? Here, then, the story. The woman, a widow, had only one son, who had become a priest. He was still fresh from ordination when the French clergy were forced by the Revolution to swear – in exchange for their life – on the “Civil Constitution” which detached that clergy from Rome and placed it under the rule of the State, of which it became an obedient body of officials. The Government itself arranged for the priests to be salaried, in exchange for the preaching of a morality that would keep the masses good and to inculcate their obedience and a “religious” obedience to the political hierarchies of the moment. Not the Christ Son of God but the philosopher Jesus, preacher of an ethic tailor-made for the worshipers of an innocuous and vague “Supreme Being.”

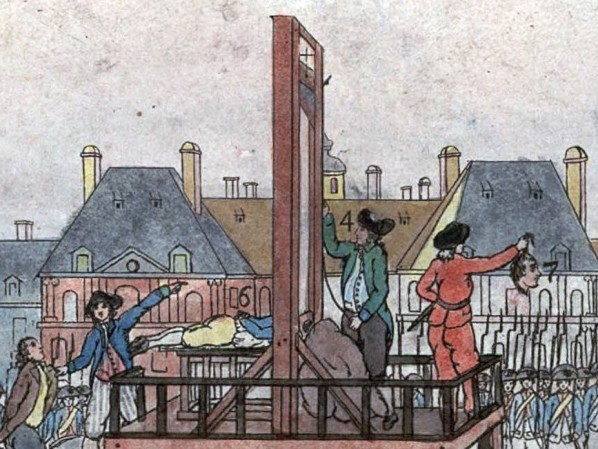

The son of Beauzac refused, like many others. The oath seemed to him blasphemous and, to avoid the guillotine as a “refractory priest,” he took to the bush. With others, he survived in the woods on the mountains that surround Le Puy but sometimes, at night, he came stealthily home to embrace his mother, happy of course to give her something nutritious and hot to eat. Some neighbors, the usual ignoble spyons born of every totalitarian regime, denounced the fact to the local Jacobins. The woman was immediately arrested and dragged before the so-called “people’s court.” It must be remembered that, at the time of the Terror, there were no prisons, except those where the accused spent the few hours between capture and trial. The law knew only two outcomes to the so-called “republican judgment”: either liberation or guillotine. The latter was planned for what Madame Beauzac was accused of: helping a rebel priest in the Republic, a “fanatic papist,” even if it was her son. Sentenced to death in a few minutes, without any debate (the law also denied a lawyer to anyone accused of similar “anti-patriotic crimes”) she was immediately taken to the gallows.

Going up on stage, she turned to the people attending and said only a few, but terrible words that have been preserved by an eyewitness: “A bitch can feed her babies but a mother cannot feed her child if not with the price of life.” Then, turning to the “patriotic” executioner, a volunteer who kills the enemies of the revolution with pleasure and flaunted the Phrygian cap: “You are more ferocious than the most ferocious beasts.” A few moments later, her head rolled into the basket under the blade.

I do not know condemnation more definitive, in its essentiality, of that ideological delirium. But yes, I really want to hug her, that intrepid mother; and I want to tell you that, since I could not do anything else, I at least exhumed her name, revealing it to the usual twenty-five readers of Manzonian’s memory.

(From Il Timone, November 2014. 2019©AP. Used with permission)

Follow

Follow