Joaquim Magalhães de Castro

One of the most prized diving destinations in the Philippine archipelago, on the small island of Culion, north of Palawan, hides a dark past that few know about. There used to be a leprosarium there since 1906, the first effort by the North Americans to establish some kind of public health policy following the signing in Paris on December 10, 1898, of the agreement that made the sale of the Spanish Philippines, “for 20 million dollars,” to the United States.

There had been a Franciscan mission in Culion since the beginning of the 18th century, which had introduced sweet potatoes, corn and modern methods of agriculture there. The missionary work would be continued by the Jesuits, of whom José Maria Algue and Manuel Valles would stand out, responsible for the construction of a chapel for catechesis and ministering of sacred offices. Soon several sisters of St. Paul from Chartres would come to the mission’s aid.

Father Manuel Valles recorded in a diary his experience with lepers, “people without noses and ears,” for whom he played the guitar and sang, teaching them Marian hymns “in Spanish, Latin and the local language.” Anointing of the sick, confessions, deaths and funerals followed one another.

Valles visited the hospital at least once a day to offer the last spiritual solace to the dying. Some asked him to write to their families, but “out of the hundreds of letters a year, only a handful were answered.” Family members were afraid to open the letters from the leprosarium even though they knew they were written by the hands of the missionaries…

Marriage was prohibited, “to guarantee the extermination of the disease,” and the lepers had their own government and a police force “to maintain law and order.” The missionaries functioned as spiritual advisers and always used every resource to defend the rights of the “exiles”.

Gradually, the American Jesuits took on the arduous task of carrying out hospital work in what would be considered a “global laboratory for scientific research on leprosy.” In 1936, Father Hugh J. McNulty founded the Culion Catholic Primary School for the education of children of lepers. Over time, a high school and college would also emerge, now known as Loyola College. In this cursed place – nicknamed “island of the undead” – where so many refused to go, there was no lack of volunteers, many of them Filipinos. These were replacing the North American confreres, following the trend of local priests assuming positions of responsibility in areas previously in the hands of Western missionaries.

In 1950, with the enactment of a law prohibiting discrimination against lepers, Culion’s mission would lose relevance, but the priests refused to stand still: they concentrated on education and got to work on projects that would guarantee food and drinking water to the local indigenous people. “The Jesuits have developed a system to capture and store rainwater for safe consumption,” Father Adriano Tapiador, one of the present resident Jesuits, told UCA News.

The bayanihan spirit, that is, “disinterested community help,” would be fundamental for the realization of these projects. A community spirit still very much alive among the Tagbanuas, natives of Culion, who consider themselves guardians of the island. Today in the minority, the Tagbanuas live essentially on fishing and almost all of them profess Catholicism. They also suffer from discrimination, not only because of their physical appearance but because of the high level of illiteracy present among the different communities on the island.

Since 2006, the Jesuits have been involved in literacy programs, in addition to promoting the awareness among these indigenous people of their rights, indicating strategies that enable them to better protect their ancestral lands and guarantee their economic, social and cultural well-being.

In the last few years, Asian priests such as Father Adriano Tapiador have been replacing European and American Jesuit missionaries all over the world. Of the current 17,000 priests and lay people of that religious congregation, about 33% are Asians, mainly Indians and Filipinos.

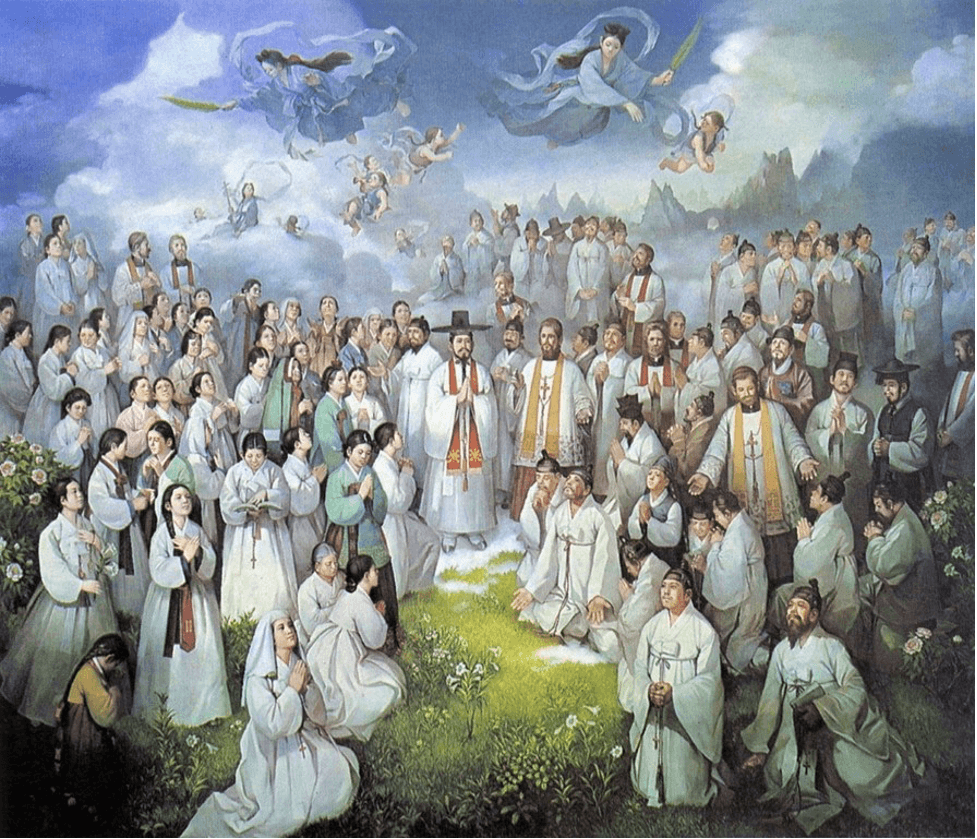

Since their arrival to the Philippines in 1581, the Jesuits have had as primary mission the areas of education and formation of character. However, it was not until the beginning of the 17th century that the first seminaries were established with the view of recruiting and preparing natives for the priesthood. The Philippines, a country with more than 70 million Catholics, has only about 8,000 priests, that is, approximately one priest for every 8,750 faithful. Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle, former archbishop of Manila and current pro-prefect of the Dicastery of Evangelization, a department of the Roman Curia, stated some time ago that the ideal proportion would be, “one priest for every 2,000 Catholics.”

(Photo credit: Joaquim Magalhães de Castro)

Follow

Follow