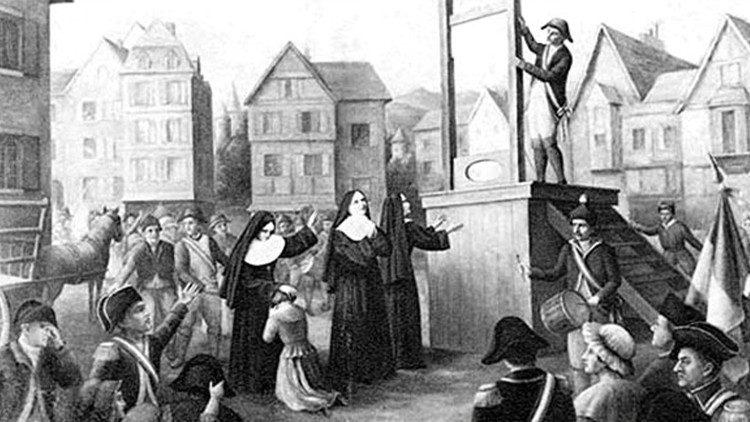

(Above) The Carmelites of Compiègne pray and sing before they are led to the guillotine

José Maria C.S. André

Sixteen Carmelite nuns died 230 years ago (November 1792) because of a dangerous prayer, inspired by a dream from a century earlier. Because of police ineptitude, the 17th Carmelite was not killed, and through her we know in detail the last days of the community.

The prioress of the Carmelite monastery of Compiègne in France found an account, almost 100 years old, of some dreams or visions of a former nun of the convent before she became a Carmelite. According to which, some of the nuns would be called to “follow the Lamb.” In the Christian context, one knows what this means. In the Old Testament, the lamb was the victim offered in sacrifice for sins, an image of Christ who died for us on the Cross. That is why Jesus Christ is often called the “Paschal Lamb.” When Jesus appears on the banks of the Jordan, John the Baptist presents Him: “Behold the Lamb of God, He who takes away the sin of the world!” The expression is frequent in Scripture, and the Eucharistic liturgy repeats it. For example, before receiving Communion, the people proclaim three times their faith in the real presence of Jesus: “Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world…” Reading the old notes, the prioress took them as a prophetic invitation to her community and interpreted the following events in that light.

The French Revolution broke out and, with the excuse of liberating France, the Regime of Terror plunged the country into the darkness of tyranny. The persecution of the Church was harsh and thorough because the revolutionaries wanted to liberate the Catholics, liberate the priests, liberate the nuns and the friars, and they were ready to use every means possible against anyone who did not want to be liberated. The pressure to liberate the Catholics increased rapidly. For example, to do away with Carmelite female convents, they suspended religious vows and subjected nuns to interrogations to make them renounce their vocation. To the great fury of the revolutionaries, most nuns of all religious orders refused to be released and decided to remain faithful until death. The nun’s habit was then forbidden; soon after, the nuns were expelled, and the state appropriated the monasteries and their contents.

The Carmelites of Compiègne took refuge in four localities, in conditions of enormous misery. Across the country, the recently invented guillotines worked frantically to cut off the heads of those who refused to be freed.

In the face of this persecution, the prioress questioned the older nuns if the community should offer their lives for the salvation of France. The first reaction of some was panic. But soon after, they apologized for their lack of courage. The prioress then made the proposal to the whole community. From then on, they all began to recite a prayer in which they offered themselves to God for the salvation of France to prevent the massacre of so many people and to ask that the multitudes in prison would be set free.

Each one prayed in silence, but the devil could not consent to such generosity. The soldiers burst into the monastery and arrested the sisters. Soon after, the mayor discovered that their poverty was such that none of them had any clothes to wear other than the religious habit. Such a crime was unforgivable. They are sent to Paris to be tried and sentenced to death. The sentencing involved the usual slanderous lies: “They are but a band of rebels, of seditious women, who cherish in their hearts the desire and the criminal hope of seeing the French people at the mercy of the swords of their tyrants and slaves of priests, who are bloodthirsty as well as impostors, and of seeing liberty swallowed up in the sea of blood, which their infamous machinations spilled in the name of Heaven…!”

The nuns understood that the mysterious call to offer their lives was being fulfilled. While they were taken as convicts through the streets of Paris, they sang the Divine Office, the usual prayer of convents. The city was moved by the voice of these poor, vulnerable, exhausted women, overflowing with a love for God and fellow citizens that seemed otherworldly.

The executioners did not have the courage to silence them. They waited for them to finish the Office, the prayers for the dying, the singing of the Te Deum (a long hymn of praise and thanksgiving, the Veni Creator (a hymn to the Holy Spirit), and finally the renewal of their vows as Carmelites.

They climbed the stage, received the blessing of the prioress, kissed an image of Our Lady and were immolated, like the Lamb offered in sacrifice. Robespierre, the main criminal promoter of the Reign of Terror, was guillotined 11 days later. Many think that the prayers of the Carmelites of Compiègne made the difference, changed the soul of France, and stopped the carnage. Pius X beatified the 16 Carmelites as martyrs, and the Vatican reported days ago that it is studying their cause for the process of canonization.

Follow

Follow