Joaquim Magalhães de Castro

Characterized by an extremely dry climate, and a rich and diverse culture, Balochistan, “a nation without a state,” has a history of civil conflicts dating back to the 17th century, which would worsen at the end of British colonial rule in 1947, and subsequent to the formation of Pakistan.

Despite being a region rich in natural resources – gas, oil, coal, copper, sulfur, marble and gold – it remains Pakistan’s least developed province, thus becoming fertile ground for all kinds of unrest. In recent times, armed separatists have been demanding greater autonomy and a greater share of the province’s natural resources. Shootings and explosions are frequent; rebels and the army mutually accuse each other of acts of violence and the disappearance of people. Taking advantage of this chaotic situation and the permeability of the borders, Islamic fundamentalists have firmly established themselves in the region and have been spreading their usual terror.

In 2013, Bishop Victor Gnanapragasam (founder of the Apostolic Prefecture of Quetta, capital of Balochistan) escaped unscathed from the detonation of an explosive device near his residence. In 2017, two suicide bombers targeted a Methodist church as children rehearsed a Christmas play. The attack, promptly claimed by the Islamic State, claimed the lives of seven of them and left 57 others mutilated. Faced with such a volatile environment, the Catholic Church reinforced security measures, and today the episcopal palace, which houses four schools aggregated in a closed complex, maintains security at all times. Other minorities – Hazara Shiites and Hindus – face similar difficulties.

In the latest wave of violence, three youths were seriously injured when a group of motorcyclists armed with machine guns attacked a Catholic community in Mastung. A fourth young man was not so lucky. He was hit by three bullets in the stomach and died. “Both men had their faces covered. It was the first time I saw terrorists,” one of the survivors told the AIS Foundation (Aid to the Church in Need) reporter.

Days later (August 11, National Minority Day) in the Chaman region, the corpse of a Christian was found with his nose and ears severed.

Following these attacks, hundreds of protesters took to the streets demanding the arrest of the perpetrators and more effective protection for local Christians. “Stop the genocide of Christians!” and “Shooting at children – shameful!” could be read on some of the posters.

“Poverty and low education produce a legion of semi-illiterate young people who are easily recruited by terrorist organizations,” says Meeran Breeseg, son of an Iranian-born academic who was forced to seek political asylum in the 1980s. First in Karachi, then in Kabul (where Meeran was born in 1985), and finally in Sweden, where he would later settle with the help of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. “My father, Taj Mahommed Breseeg, was guilty of fighting for the political and civil rights of people of Baluchi origin in Iran,” says Meeran. In his university days in Karachi, Breseeg would found a group that aimed to preserve and promote the Baluchi culture and language. “He was not fighting for an independent state, just equality of rights and opportunities for the Baluchi people. I don’t think he was asking for too much,” says our interviewee.

Thanks to the European exile, his father would fulfill his dream of joining the teaching staff of the University of Oriental and African Studies in London, the renowned SOAS, where for seven years he worked on his thesis “Baloch Nationalism – Its origin and developement,” published in 2004 and soon translated into Arabic and Urdu.

Despite being grateful to Sweden for giving him a nationality and a scholarship to complete his studies in Hawaii, “in marketing and communication,” Meeran Breeseg does not feel Swedish. And the reason for this uprooting is due to the fact that he grew up in a Stockholm neighborhood with a high density of immigrants, “mainly Somalis, but also Kurds, Iranians and Iraqis.” A trip to Thailand turned him into a “citizen of the world,” and after intermittent jobs in Sweden and Spain, he would return to Southeast Asia again, this time to take up a tourist project together with his older brother.

In the six years he lived in Spain, between Granada and Malaga, he found the human warmth he lacked in his adopted Scandinavia. “I am a very social person. I feel better here than in Sweden where everyone is more introverted,” he comments. Also, in the Iberian peninsula, he had the opportunity to make Portuguese friends and remember what his mother had always told him. That within the family, from time to time, someone was born with light eyes and blond hair, “a clear genetic heritage of the Portuguese.” Meeran speaks of the “ruins of castles and towers” scattered along the coast of Balochistan which has its origin attributed to the Portuguese and their cousins with European characteristics.

“In Balochistan, we are aware of this heritage as we know that the sailors who accompanied Vasco da Gama mixed with local women and founded families which persist till today.”

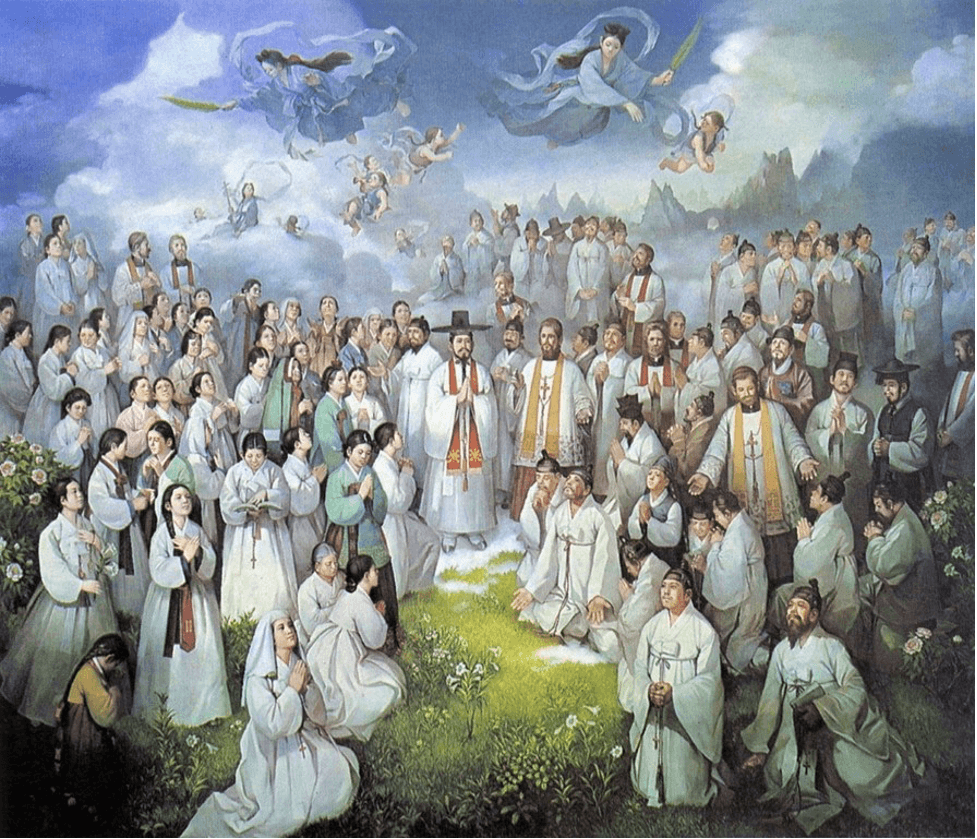

(Photo credit: Joaquim Magalhães de Castro)

Follow

Follow