Joaquim Magalhães de Castro

After a long experience of life in a region marked by acts of great violence and armed conflicts between rebel forces and government troops – we are talking about the troubled island of Mindanao in the south of the Philippines – and inspired “by the dialogue of God with people of all cultures and religions,” the Italian Sebastiano D’Ambra, priest of the PIME congregation (Pontifical Institute for Foreign Missions), together with a group of Muslim and Christian friends, founded on May 9, 1984, in the city of Zamboanga, the Silsilah Dialogue Movement. The Arabic word “silsilah,” which literally means “chain” or “link,” was (and still is) used by Muslim mystics to describe the personal process of “approaching the Divine”.

Thus, “silsilah” serves as a key and inspiring motto for what is intended: to bring together Muslims and Christians (and people of other faiths) in a common vision and mission in favor of dialogue and peace. Recognizing the uniqueness of each religion, people are invited to embark on “a process of spiritual growth through the discovery of God’s constant dialogue with humanity.” It is, in fact, a call to a life in constant dialogue, witnessing the presence of God in the plurality of cultures and religions.

Over the decades, thanks to the many summer courses and seminars held in the meantime, the Silsilah Dialogue Movement has trained thousands of Muslims and Christians, and there has been great concern to reach everyone, especially children, through initiatives in primary schools and day care centers in the poorest neighborhoods of Zamboanga. It is in this context that the ‘Tulay Bata’ initiative arises, an educational approach that invites young people to implement four pillars of dialogue – dialogue with oneself; dialogue with others; dialogue with Creation (nature and animals); and finally, dialogue with God. It simultaneously empowers parents to be active agents in the spiritual formation of their children.

The Silsilah Dialogue Movement celebrates 36 years of existence this year and, among its formative experiences, continues to offer a one-month basic course and an intensive one-week course for people of different religions and nationalities who want to learn and practice a “culture of dialogue, an experience essentially of a spiritual nature.” All participants and members of the Silsilah Dialogue Movement, aware “of our world marked by divisions and conflicts, socio-economic and ecological crises, religious and cultural prejudices,” commit themselves to living their Faith with “sincerity, love and compassion towards others,” constantly seeking the path of dialogue, appreciating the diversity of cultures, beliefs and religious traditions, so that together we can act toward “the protection and care of our common home.”

It should be remembered that the island of Mindanao, the main home of the Filipino Muslim minority (about 6 million people), has long been the scene of fighting between the Filipino army and various rebel groups. On September 9, 2013, around 100 armed militants from the MNLF (Moro National Liberation Front), breaking a peace agreement signed with the Government of Manila in 1996, entered Zamboanga and took 30 civilians hostage, later using them as human shields. As a result of the ensuing clashes with government forces, six of these people died and the other 24 were injured. As always, the local Catholic Church, through the voice of Msgr. Crisologo Manongas, the then apostolic administrator of the Archdiocese of Zamboanga, expressed its indignation and appealed to the leaders of the MNLF not to involve innocent civilians in their political claims and to dispose the weapons, because with them they would solve nothing.

Meanwhile, hundreds of displaced people found refuge in public buildings and the archdiocese’s churches, which promptly opened their doors. As Msgr. Crisologo Manongas reminded Fides News Agency at the time, “this is not a religious conflict, but a political one. There is no animosity between Muslims and Christians.”

The MNLF accused the government of having violated the 1996 agreement by openly negotiating with a rival rebel group, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF).

Mindanao, with a population of 24 million, has a history of four centuries of Moro resistance against external forces, and the conflict with the central government has lasted since the late 1960s. The Communist New People’s Army is active throughout the country and the terrorist Islamic State remains the main threat in Mindanao. The 2017 siege of the city of Marawi, in Lanao Del Sur province, was a five-month battle between pro-Islamic State fighters and the Philippine military, and would result in a wave of 400,000 refugees. The establishment of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) in March 2019 would be an important step towards resolving the conflict, although Bangsamoro’s self-styled Islamic Freedom Fighters and the infamous Abu Sayyaf Group, linked to the Islamic State, continue to refuse to lay down their arms.

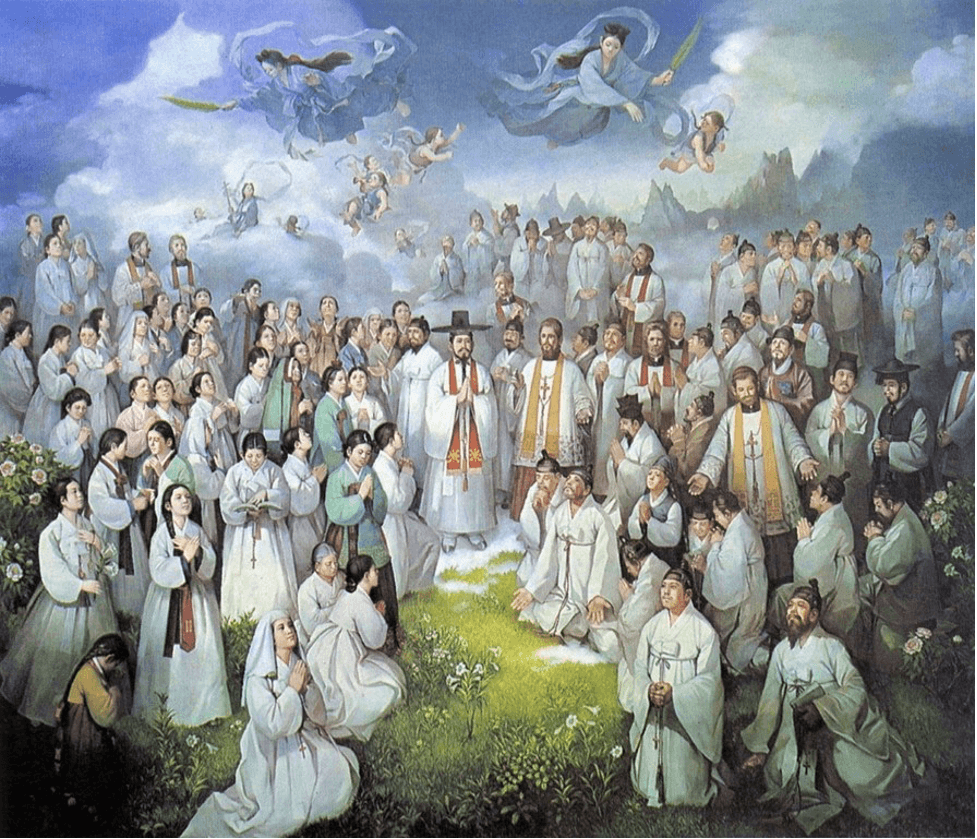

(Photo credit: Joaquim Magalhães de Castro)

Follow

Follow