Miguel Augusto

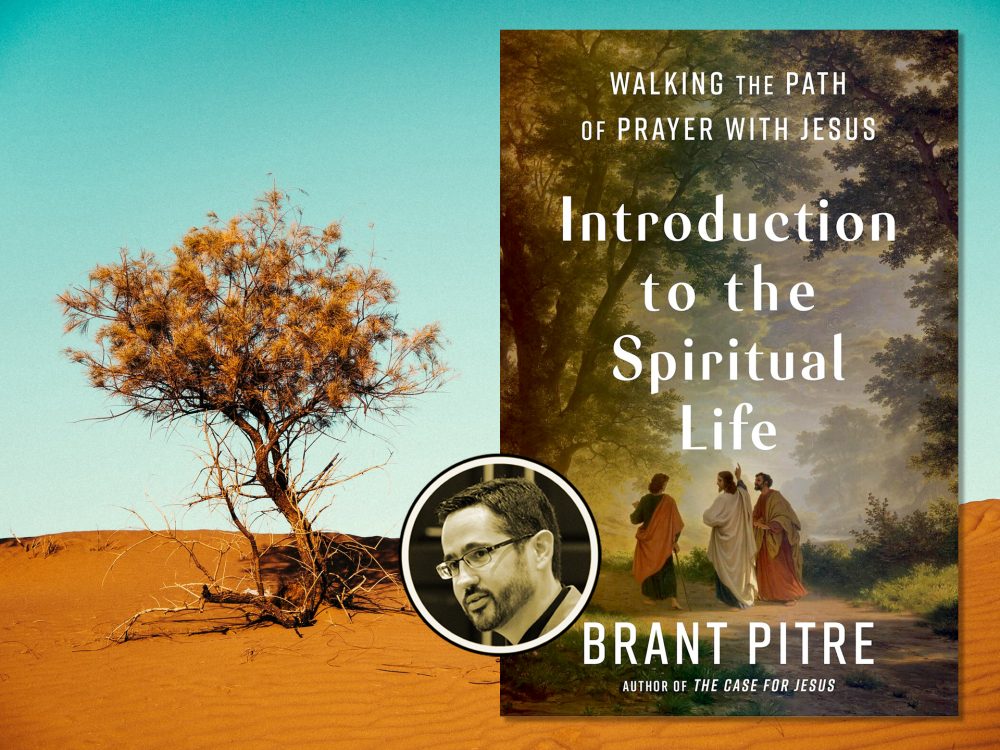

Lent, which began last Ash Wednesday, is characterized by a long period of six weeks until Easter. It is a journey of purification and spiritual growth. For this purpose, three spiritual practices are asked: prayer, fasting and almsgiving. Scripture scholar Brant Pitre in his recent book Introduction to the Spiritual Life: Walking the Path of Prayer with Jesus, gives us guidelines for a Christian spiritual life. He starts with the maxim that the path of prayer is not only informative but transformative.

Earlier this year, Tim Gray, President of the Augustine Institute, spoke with Brant Pitre about his spiritual work. From the enriching dialogue, available on the Augustine Institute’s YouTube channel, we have taken notes that may serve as inspiration, for a journey of growth in prayer and with Christ this Lent.

The academic Brant Pitre – distinguished research professor of Scripture at the Augustine Institute – spoke of his own journey of growth in faith as a Catholic Christian. He said he has tended to think of prayer and the spiritual life primarily by vocal prayers – a prayer before a meal or saying prayers before going to bed at night. “Or maybe, even saying a little bit longer prayer like the Rosary,” he concluded.

The professor, however, found that when he started reading the spiritual classics, works such as those of St Francis de Sales, St John of the Cross, or St Teresa of Avila, one of the things he realized was that, according to the saints, the spiritual life of a Christian is much more than just “saying your prayers or that vocal prayer.” But that involved practices of prayer that we often do associate with like eastern religions – “Things such as meditation or contemplative prayer, which at time, when I first started studying, I wasn’t even sure what exactly those things meant.”

As a Biblical scholar, Brant says he began to recognize we might have all these different spiritual traditions within the Christian Church like the Carmelite spirituality or Ignatian spirituality of the Jesuits, but at the end of the day, they were all drawing from one common source, and that is the spiritual master of all spiritual masters who is Christ Himself.

In this way, Pitre says he tried to incorporate in his book all those basic elements of Christian spirituality – prayer, fasting, almsgiving, the seven capital sins, the opposing virtues, examination of conscience. But he wondered: “Where are they in the Old Testament? Where are they in the teachings of Jesus? And then: what does the Apostolic preaching and the tradition tell us about how to put them into practice in our daily lives?”

Brant says it was very crucial to break his mindset of thinking of Christianity as a mere set of external laws imposed on us. While he is aware that true Christianity has a deep moral core, and it is a moral code of life, he says it’s important to recognize that the spiritual life is not just that. “When Jesus talks about spiritual growth, He talks about it using the image of a path, or a way. It’s a journey, a road; one way that leads to eternal life,” Pitre stresses.

For the professor, Bible study is not just reading the Bible. “It’s about pondering the Scripture and taking it not only ‘to my mind’ but also ‘to my heart’; groaning over, sighing over the truth.” In a strong appeal, Brant recalls that every single Christian is called to meditate on the Word of God every single day. Jesus says: “It is written: ‘One does not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes forth from the mouth of God.’” (Matthew 4:4). “It should be our spiritual food, it’s our spiritual nourishment,” exulted Brant.

On contemplative prayer, Pitre points out “it is what David describes in Psalm 27. His desire to seek the face of the Lord. And his desire also to be gazed upon by the Lord. Gaze of love between the soul and God.”

Here, as a scholar, he poses a question, “If you think well, where’s this in the gospels. The spiritual classics will all point to one key passage in the scriptures [Luke 10:38-42]. It’s the famous story of Mary and Martha. We all know the story, right? Martha is very busy, she’s very active. She’s trying to show hospitality to Jesus and prepare a meal for Him when He’s coming to the house. But Mary, her sister, is sitting at the master’s feet gazing up at His face and just quietly listening to Him. In the 1st century Jewish setting, that posture of sitting at his feet was actually the standard posture of a disciple to a master, of a disciple to a rabbi.”

Pitre noted that the saints are going to use that image of Mary as a kind of model for contemplative prayer. “When I started reading this spiritual classic’s twenty years ago, primarily what I encountered were commentators on Scripture. I saw these mystics and saints saying over and over again: this experience of prayer that I had flowed out of this passage in the gospels. Or this song, or this episode from the life of Jesus. And I was blown away by how deeply biblical authentic Christian spirituality really is; and not just biblical, but Christocentric.”

In this way, it became clear to Brant that the Christian spiritual path and life is not just about this or that method of prayer, or mystical experiences. But, at the heart of it, the saints and the spiritual classics agree that the goal of prayer, of meditation, of contemplative prayer, is growth in virtue by growing closer and closer to Jesus Christ. Pitre says that in particular, the saints will often express that by looking at the opposite of virtue – the seven capital sins. Things like pride and disordered love of self, or anger, envy, avarice, less greed as what gluttony. Virtues like humility and mercy, generosity, chastity, temperance, and diligence. “I began to realize this means that walking the path of prayer with Jesus is gonna make some demands on me: he’s calling me to grow in virtue and to bear fruit.”

The professor recalls here that Jesus compares the human soul to a tree. A good tree bears good fruit, and a bad tree bears bad fruit. In this analogy, Brant concluded that if the soul is like a tree, then the health of one branch can strengthen the health of the other branches. Similarly, the sickness of one branch can affect the whole tree. He gives us some advice: “Focus on one virtue whatever your predominant fault might be and try to grow in it.”

On suffering, the professor warned that suffering can be a temptation to turn away from God. Here he points us to a path to follow: the example of the saints who will counteract this ungodly sadness with the virtue of the will to suffer with patience. He reminds us, “The endurance of Christianity is a willingness to accept my own participation in the mystery of the cross. It is a redemptive suffering where I allow myself to be conformed to Christ crucified, not because of the pain itself, but because through the love of the Cross, suffering is transformed and becomes redemptive. It has the power to change hearts, to change souls, to change myself; and the power to participate in the salvation that Christ brings through the world.”

Follow

Follow