Aurelio Porfiri

About more than 25 years ago, I had the opportunity to spend a few hours in conversation with a well-known Jesuit biblical scholar, Ignace de la Potterie (1914-2003). If I remember correctly it was June 1996. Both of us had been invited to a spiritual retreat by the Legionaries of Christ, I was an organist and he was a preacher. At one point we started chatting and our discussion went on for a long time. I must say that, after initial distrust, Father de la Potterie was very resourceful in our discussion. It seems to me that we talked about the theme of the gaze of Christ, which he had dealt with for a long time.

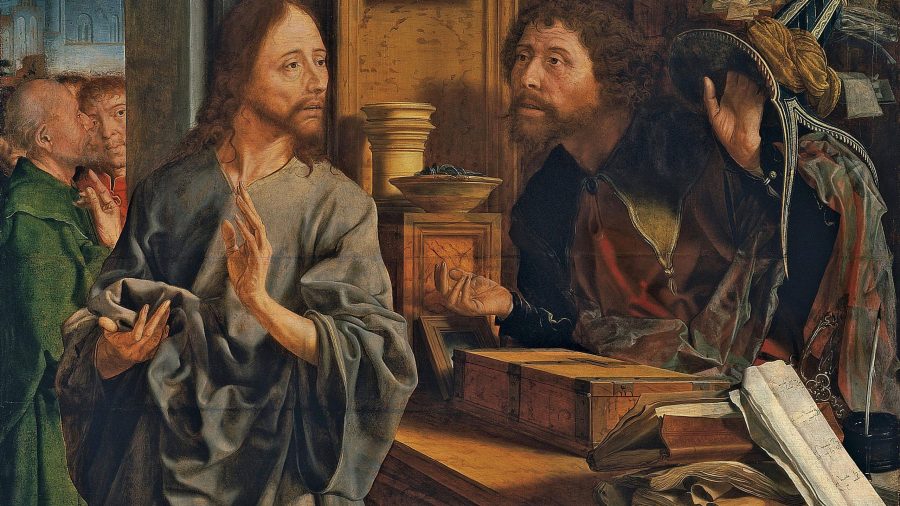

This encounter came to mind when looking at a seventeenth-century painting in the Louvre, The Vocation of Saint Matthew. We all know the story, that of Jesus calling the hated tax collector to follow him. The unknown author of the painting sets up his work with five characters: Jesus, Matthew and three other people. It can be observed that in the painting it is all a game of glances, but that of Christ is fixed on Matthew, who seems instead intent on counting the money and looking at an undefined point.

What must have been the gaze of Christ? The other characters have a focus in their gaze, it really seems to witness a chain of glances that start from the character on the far left of the picture that through a woman reaches Christ, who is distinguished by a particularly bright face and through a young man arrives at Matthew who, as mentioned, does not look back at the moment. Precisely in the synoptic gospels we find the account of the vocation of St. Matthew. Let us read the passage as it appears in Matthew’s own Gospel: “Going away from there, Jesus saw a man, called Matthew, sitting at the tax office, and said to him: ‘Follow me’. And he got up and followed him”. Jesus saw a man. That is, before seeing the hated tax collector by all, he saw a man for who he was and asked him to follow him. It seems to me that in the painting that we are talking about, the moment is fixed in which in the web of glances, that of Christ is fixed on Matthew.

Let’s go back to what Ignace de la Potterie himself said in an interview with Antonio Socci in the magazine Il Sabato (now in atempodiblog.unblog.fr) about this theology of seeing: “The starting point is what we see with these eyes of our flesh: one begins with the signs, such as the empty tomb or the gardener, a real man whom Mary Magdalene encounters, who then recognizes him as Jesus… It is a progression. Moreover, talking about the verb ‘to see’, first the Greek verb ‘bleso’, which means to see, to notice something. Then ‘theorein’ that we find for the Magdalene and it means to look carefully, to observe. Then the verb ‘horan’, in the perfect Greek which expresses the perfect form of the verb ‘to see’ and which I would translate here ‘now I see perfectly, I contemplate the profound meaning of what I see’. So from realizing something to contemplating the Mystery of God in visible reality, this is the dynamics of the first Christian faith, according to the Gospels”. Here, this theology of seeing according to Father de la Potterie is particularly important in the Gospel of John, which I want to reflect (but it is only my interpretation) to be that young man in the painting who is almost at the center and who seems to be looking in the direction in which Christ looks and write something.

What must have been the gaze of Christ?

(Image: The Calling of Saint Matthew, c. 1530. Found in the collection of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collections. Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images

Follow

Follow