Rev José Mario O Mandía

jmom.honlam.org

“Like all the other sacraments, penance is a liturgical action,” says CCC 1480.” Then it lists down the elements included in the rite: [1] the priest and the penitent make the sign of the cross after which the priest greets the penitent and exhorts him to confess his sins “with true sorrow” (Rite of Confession); [2] the penitent confesses his sins; [3] the priest gives some advice and imposes the penance; [4] the priest gives the absolution and may end with “a prayer of thanksgiving and praise.”

In the Latin Church, there are three Rites of Reconciliation:

1. Rite for the Reconciliation of Individual Penitents. The CCC 1484 teaches: “‘Individual, integral confession and absolution remain the only ordinary way for the faithful to reconcile themselves with God and the Church, unless physical or moral impossibility excuses from this kind of confession’ (Ordo Paenitentiae 31). There are profound reasons for this. Christ is at work in each of the sacraments. He personally addresses every sinner: ‘My son, your sins are forgiven’ (Mark 2:5). He is the physician tending each one of the sick who need him to cure them (cf Mark 2:17). He raises them up and reintegrates them into fraternal communion. Personal confession is thus the form most expressive of reconciliation with God and with the Church.” Saint John Paul II reiterated this in the Apostolic Exhortation Reconciliatio et Paenitentia (no 33) and on other occasions, for example, in his 2002 Letter to Priests (cf no 9).

2. Rite for Reconciliation of Several Penitents with Individual Confession and Absolution. CCC 1482 describes this form.

“The sacrament of Penance can also take place in the framework of a communal celebration in which we prepare ourselves together for confession and give thanks together for the forgiveness received. Here, the personal confession of sins and individual absolution are inserted into a liturgy of the word of God with readings and a homily, an examination of conscience conducted in common, a communal request for forgiveness, the Our Father and a thanksgiving in common. This communal celebration expresses more clearly the ecclesial character of penance. However, regardless of its manner of celebration the sacrament of Penance is always, by its very nature, a liturgical action, and therefore an ecclesial and public action (cf Sacrosanctum Concilium 26-27).”

3. Rite for Reconciliation with General Confession and Absolution. This extraordinary form is described in CCC 1483.

“In case of grave necessity recourse may be had to a communal celebration of reconciliation with general confession and general absolution. Grave necessity of this sort can arise when there is imminent danger of death without sufficient time for the priest or priests to hear each penitent’s confession. Grave necessity can also exist when, given the number of penitents, there are not enough confessors to hear individual confessions properly in a reasonable time, so that the penitents through no fault of their own would be deprived of sacramental grace or Holy Communion for a long time. In this case, for the absolution to be valid the faithful must have the intention of individually confessing their grave sins in the time required (cf Code of Canon Law, can. 962, § 1). The diocesan bishop is the judge of whether or not the conditions required for general absolution exist (cf Code of Canon Law, can. 961, § 2). A large gathering of the faithful on the occasion of major feasts or pilgrimages does not constitute a case of grave necessity (cf Code of Canon Law, can. 961, § 1).”

Note the emphasis on personal confession and absolution. Christ, the Good Shepherd, always tends his sheep one by one.

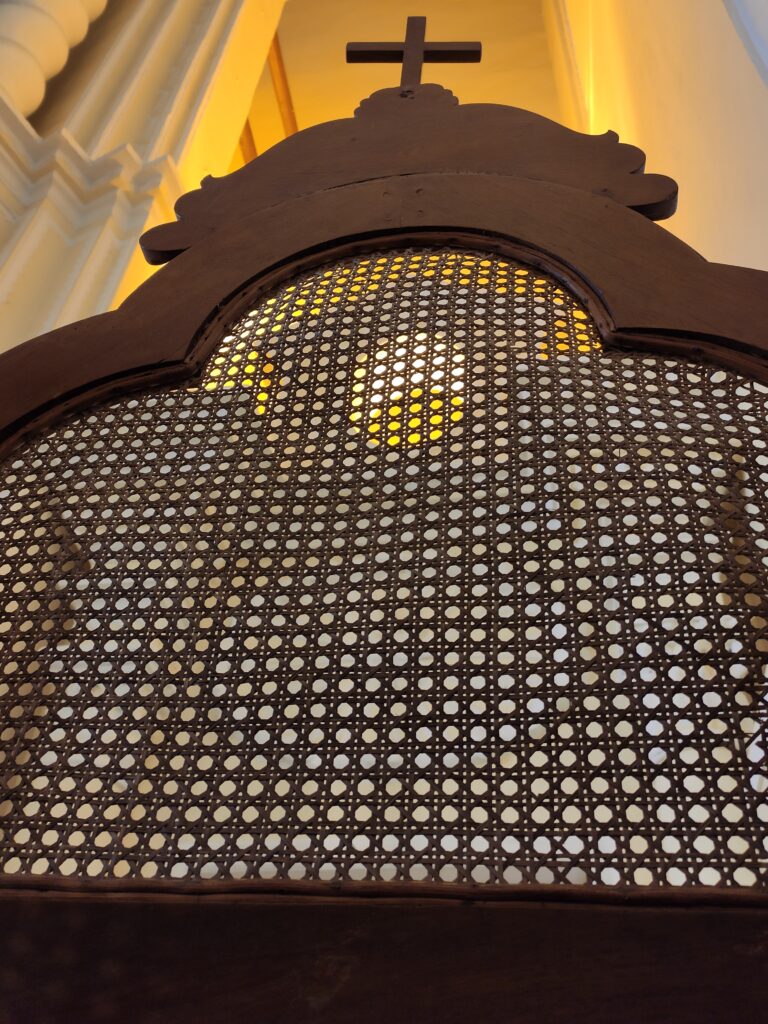

(Photo by José Mario O. Mandía)

Follow

Follow