Enrico Finotti

I am a priest from the diocese of … I always follow you and read with great interest, trying to implement your precious indications in the parish entrusted to me. I would like to open my mind to tell you what the liturgical formation we have had since the seminary and then the refresher courses … We were told that the liturgical books should not be mandatory, but should be used as a general indication to guide our creativity. In short, the book was not to be read, but recreated with our own words according to the assembly for which it was celebrated. We were all afraid of being considered ‘rubricists’ and we felt (in good faith) authorized to freely remake rites and texts. It seems that this was not the Church’s thinking … Please clarify …

The concept of the liturgical book as a ‘canvas’, that is, a general indication rather than a mandatory rule for the celebration of rites, has been strongly detrimental to liturgical law and a non-negligible cause of creativity detached from the objectivity of liturgical actions and therefore a reason for multiple abuses.

In reality, the liturgical tradition of the Church develops in the sense of the ever more precise and detailed determination of the ritual laws, passing from the relative freedom of the first centuries to the rubric precision of the Council of Trent.

This process is not to be considered negative, as if the monumental construction of liturgical law that took place over time was a derailment from the ‘freedom of the spirit’ and the authenticity of worship, as it was originally assumed. It is in the intrinsic nature of the liturgy to demand the precision of law and to make explicit the tenor and meaning of the rites and precepts with ever more defined determinations. Since the subject of the liturgy is Christ, indissolubly united to the Church, his mystical body, it is necessary to know with certainty the content of his thought and prayer and to identify the specific form of his saving acts. The law of objectivity is in this sense fundamental in the liturgy, and it is this that ensures the Christian people to adhere with certainty to the integral worship that Christ the Head, in indissoluble union with the Church his bride, raises to divine Majesty. To reach this supernatural reality, targeted laws are needed, which shape the liturgy, so as to clearly distinguish it from the changing subjectivism of human sentiments. The liturgy writes its best pages not in the juridical uncertainty of its acts, but in the faithful adherence to its juridical apparatus, as an organic, coherent and noble reflection of divine law. The reform intervention must not indulge in principle in a reckless reduction of the law and its wise norms, but rather aim at an indefatigable and ever higher perfection of liturgical law in order to reflect, with the greatest possible fidelity, the cult itself, of the only-begotten Son of God. The secret and sublime strength of the liturgy lies in its engagement with the cult of Christ, the high priest, and not in presumptuously assuming our fragile and ineffective stammering of creatures weakened by sin.

Certainly, the dominant anthropocentric mentality, inspired by subjectivism, individualism and sentimentality, cannot but feel threatened by the solemn grandeur of a liturgy defined, stable, clear, objective in its contents, perennial in its substance and screened in the crucible of a tradition of the centuries.

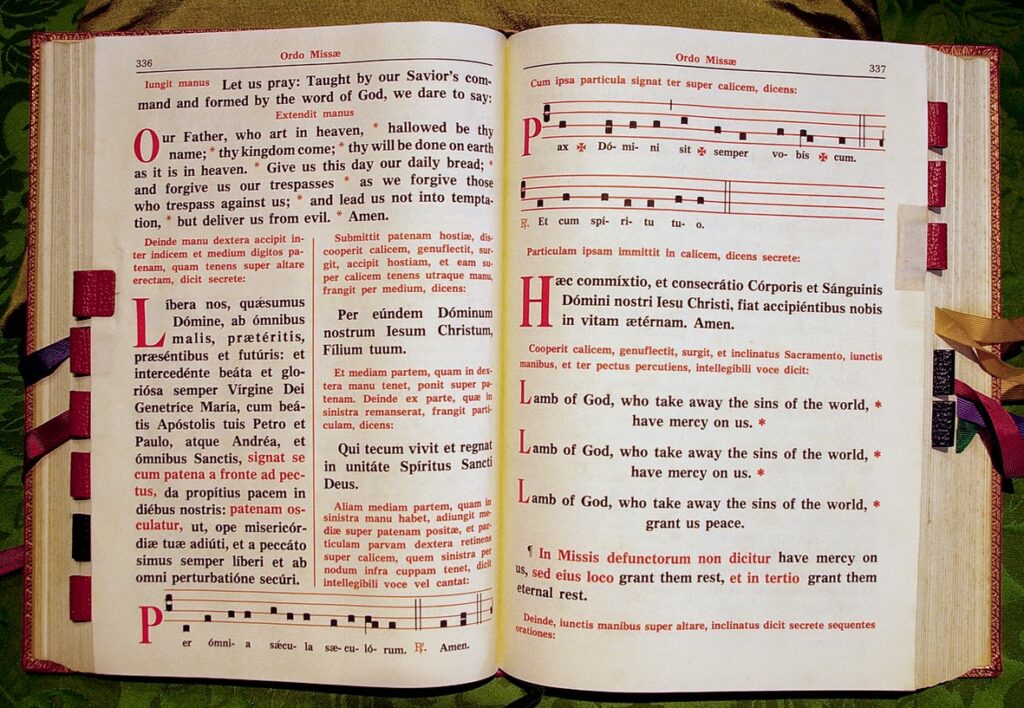

The liturgical book is then a gift that the Church makes available to her priests and to all the people of God and must be followed in a perceptive way and with a grateful soul. The Church also establishes the degree of obligation of the various liturgical laws and allows adequate spaces for choice and freedom, which however must be used with a liturgically trained intelligence.

(From La spada e la Parola. Il liturgista risponde, 2018©Chorabooks. Translated by Aurelio Porfiri. Used with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved) (Photo from The Saint Bede Studio Blog)

Follow

Follow