Rev José Mario O Mandía

jmom.honlam.org

The CCC (no 1447) gives a brief history of the rite of the Sacrament of Penance.

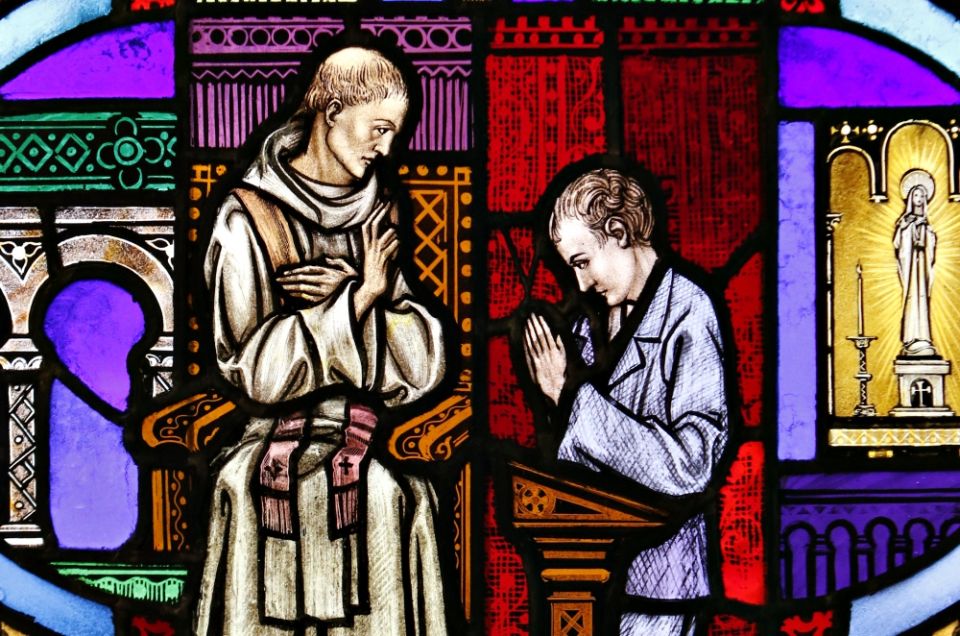

“Over the centuries the concrete form in which the Church has exercised this power received from the Lord has varied considerably. During the first centuries the reconciliation of Christians who had committed particularly grave sins after their Baptism (for example, idolatry, murder, or adultery) was tied to a very rigorous discipline, according to which penitents had to do public penance for their sins, often for years, before receiving reconciliation. To this ‘order of penitents’ (which concerned only certain grave sins), one was only rarely admitted and in certain regions only once in a lifetime.

“During the seventh century Irish missionaries, inspired by the Eastern monastic tradition, took to continental Europe the ‘private’ practice of penance, which does not require public and prolonged completion of penitential works before reconciliation with the Church. From that time on, the sacrament has been performed in secret between penitent and priest. This new practice envisioned the possibility of repetition and so opened the way to a regular frequenting of this sacrament. It allowed the forgiveness of grave sins and venial sins to be integrated into one sacramental celebration. In its main lines this is the form of penance that the Church has practiced down to our day.”

The main elements of the Sacraments, however, have always been the same.

MATTER

(1) Remote matter: the sins of the penitent. A distinction is further made between sufficient matter and necessary matter.

(1.1) Sufficient [Remote] Matter: any venial sin for which one is sorry, or mortal sins already forgiven in previous confessions. By “sufficient matter” we mean the minimum needed for a confession to be valid. In other words, a person who just confesses mere imperfections or weaknesses cannot be absolved because there is no sin to absolve.

“Indeed the regular confession of our venial sins helps us form our conscience, fight against evil tendencies, let ourselves be healed by Christ and progress in the life of the Spirit. By receiving more frequently through this sacrament the gift of the Father’s mercy, we are spurred to be merciful as he is merciful (cf Lk 6:36)” (CCC 1458).

(1.2) Necessary [Remote] Matter: every single mortal sin committed after the last good confession (cf CCCC 304: Which sins must be confessed?). “Necessary matter” means that this kind of matter must be confessed for the confession to be valid. If it is deliberately omitted, the confession is invalid and, moreover, one commits the sin of sacrilege. Should one forget, he should not worry – his sins are forgiven, but he should try to bring it up in his next confession.

(2) Proximate matter: the acts of the penitent (i.e., what the penitent does with his sins). “They are: a

(2.1) careful examination of conscience;

(2.2) contrition (or repentance), which is [2.2.1] perfect when it is motivated by love of God and [2.2.2] imperfect if it rests on other motives and which includes the determination not to sin again;

(2.3) confession, which consists in the telling of one’s sins to the priest; and

(2.4) satisfaction or the carrying out of certain acts of penance which the confessor imposes upon the penitent to repair the damage caused by sin” (CCCC 303).

Note that contrition does not refer to a feeling. As someone has said, “Repentance is not when you cry, but when you change.”

Regarding the confession of sins, St Josemaría summarized the characteristics of a good confession in four points. It should be:

(2.3.1) clear: the confessor understands what is being confessed;

(2.3.2) complete: one should say what needs to be said, e.g., all the mortal sins he has committed since the last confession, and details of his sin which may alter its seriousness or gravity (e.g., intention, circumstances);

(2.3.3) concrete: especially in the case of a grave or mortal sin, he should say what exactly he did or did not do.

(2.3.4) concise: he should say only what needs to be said and nothing more.

FORM

The form of the Sacrament is the words of absolution: “And I absolve you from your sins, in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen” (cf CCCC 302).

Follow

Follow