– Benedict Keith Ip

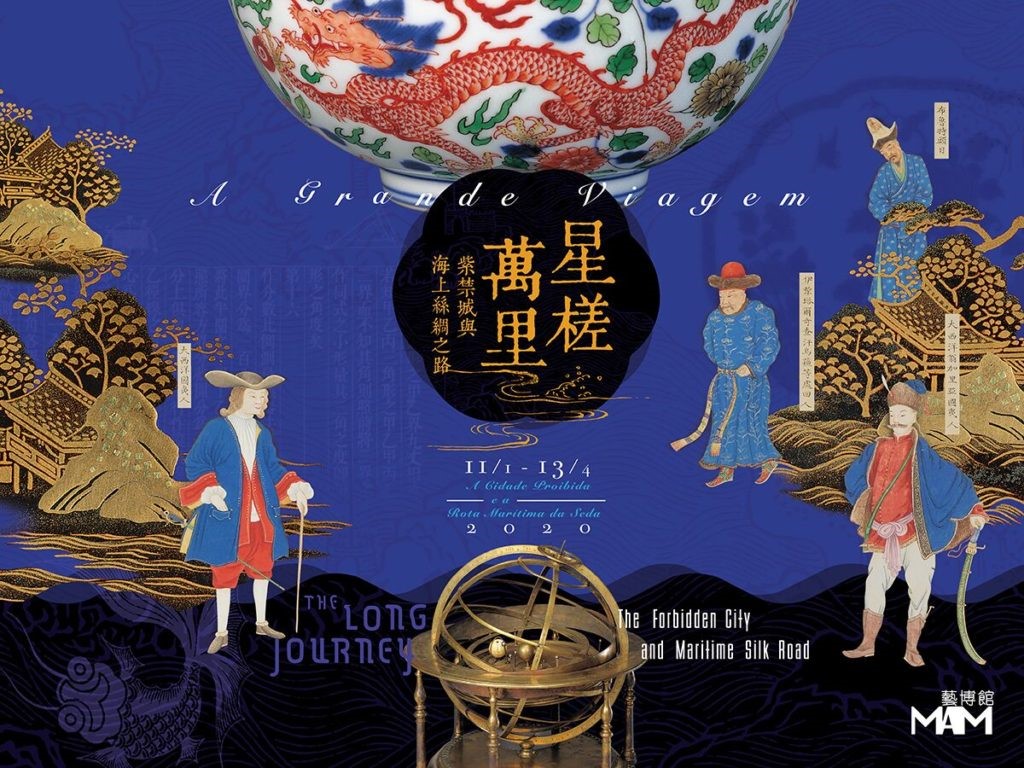

Together with the Palace Museum, the Macau Museum of Art brings to the public a great exhibition related to the Maritime Silk Road in Macau. An opening ceremony has unveiled the exhibition at 11 AM on the 11th of January.

The main thematic exhibition of The Long Journey: The Forbidden City and Maritime Silk Road takes place at the 4th floor gallery of the Macau Museum of Art. It features a total of nearly 150 exquisite cultural relics from the collection of the Palace Museum related to the Maritime Silk Road. These cultural relics are mostly from the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties, including tributes presented by foreign envoys, gifts and objects brought by Western missionaries, and calligraphy and paintings actually produced in the court by these missionaries, as well as various goods purchased by or custom-made for the court, or made by imperial or provincial workshops by imitating and creatively adapting imported products, in addition to items from the collection of the Macau Museum of Art. All of them highlight the rich fruits of the Ming and Qing courts’ exchanges and interactions with the outside world, illustrating the splendor of the Forbidden City culture in fine contrast with other cultures along the Maritime Silk Road.

The arrival of Western missionaries to China at the end of the Ming and beginning of the Qing was a turning point, bringing a wave of Catholicism and Chinese-Western cultural exchanges that had a profound impact on China. From the 16th century on, numerous Western missionaries and artisans came to serve long-term positions in the imperial court, bringing new knowledge in subjects such as astronomy, mathematics, medicine, geography, firearms production, art, and music, as well as varied apparatus like Western clocks and astronomy instruments.

The court painter’s illustrations of diplomatic envoys from foreign countries and vassal states in painting Wanguo Laichao Tu (All Nations Coming to the Court), the gold-leaf memorials presented by envoys from tributary countries when entering the palace to offer tributes, the various foreigners and ethnic minorities paying tributes to the Qianlong Emperor in Huangqing Zhigong Tu (Qing Imperial Illustrations of Tributaries) – all these are detailed manifestations of Qing political and diplomatic clout.

At the juncture of the Ming and Qing, Matteo Ricci, Johann Adam Schall von Bell, Ferdinand Verbiest, and many other Western missionaries made the long overseas journey to China, where they found success in spreading Christianity by introducing Western technological instruments to befriend upper level officials and scholars. That way, they were allowed into the Chinese imperial court, to directly impart Western scientific knowledge to the emperor. The Kangxi Emperor, who particularly loved learning, appointed Western missionaries as his teachers in various fields of knowledge, such as math, astronomy, and calendars. This exhibition includes the (translated) study materials of Emperor Kangxi, as well as a desk specially made for him to perform mathematical calculations, both of which reflect the emperor’s marked interest in seeking Western knowledge.

In the 8th year of the Kangxi reign (1669), an armillary sphere was manufactured under the supervision of the Belgian missionary Ferdinand Verbiest. This small model of celestial bodies came to be used in the Qing imperial court. It could show how the sun and moon revolve around the Earth or demonstrate the phenomena of solar and lunar eclipses, reflecting the advances of Western astronomy. As a furnishing of the imperial palace, the armillary sphere appeared in imperial paintings from the Yongzheng period. Western clocks were also cherished by the Ming and Qing courts which collected British clocks in the form of a pagoda with an elevating mechanism that boasted a complicated structure and ingenious design. Besides serving to keep time, the clocks were also finely decorated with still and moving figures, running water, flowers, and more. Emperor Qianlong was fascinated by Western clockwork, believing that Western-made objects were the best in the world. In fact, these amazing Western gadgets created quite a distinctive ambiance in the Chinese imperial court.

Since the late Ming, Chinese painters had been making great efforts to learn Western painting techniques. In the Qing dynasty, Western painters found a way into the court and brought new elements into traditional Chinese painting. These ‘court artists’ created portraits, landscapes, bird-and-flower and even garden layouts. Among them, Giuseppe Castiglione (aka Lang Shining), Jean-Denis Attiret (aka Wang Zhicheng), and Ignatius Sichelbart (aka Ai Qimeng) were the most important and familiar ‘foreign painters’ from the Kangxi to Qianlong eras, with their precious works still gracing the collections of the Palace Museum. Jean-Denis Attiret’s bird-and-flower paintings and Ignatius Sichelbart’s Ten Fine Dogs album are considered successful emulations by Western artists; scenic illusion paintings (tongjing hua) in the Juanqinzhai (or the ‘Studio of Exhaustion From Diligent Service’) in the Palace Museum is a perfect example of the use of Western perspective in court paintings.

The exhibition will be available from January 11 to April 13 at MAM. It opens from 10 AM to 7 PM (admission will stop after 6:30 PM) including public holidays and closed every Monday. For inquiries, please dial 87919814, website: www.MAM.gov.mo.

Follow

Follow