– Joaquim Magalhães de Castro

The hermitages scattered around the monastery of Chagri are still occupied by monks who remain there for several months in total silence and without any contact with their peers, not even those who supply them at a distance with food, in the case said ascetics are not fulfilling strict periods of total fasting.

In his writings Estêvão Cacela refers to the objects manufactured by Shabdrung during this spiritual retreat. Among them “an image of God’s figure in white sandal, small but excellently made” and some paintings that still today are a reason for reverence on the part of the Bhutanese. Apparently, his artistic penchant was such that, seeing the image of the Archangel Saint Raphael taken by the priests, Shabdrung showed a willingness to make a copy of it. Cacela assured us that he soon set to work “and he was continuing very well, but he had so many occupations he has not yet able to finish it.” It would be interesting to know the whereabouts of that painting…

Still in what concerns the artistic gifts of the Bhutanese king, as a painter and sculptor, Cacela says that “all his art and curiosity, he uses to make images of his father and to decorate them very well, and this one is kept in a house that he made for prayer, in which only this image of a big size is inside a good and beautiful sepulcher of silver.” The “house” mentioned by the Jesuit is, in fact, the guarding temple we mentioned last week, the main place of worship throughout the monastic complex.

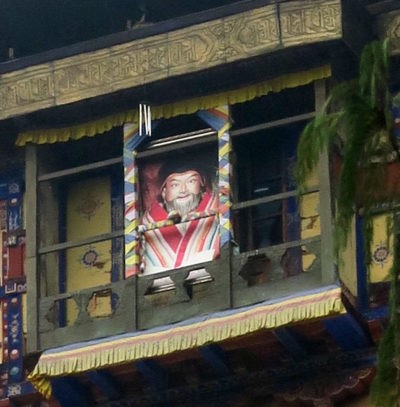

Cacela also gives us the first and perhaps the only physical description of this historical character. He tells us that Shabdrung’s beard was so long that “part of it reached his waist,” and for this reason the Bhutanese king wrapped them in a silk cloth and only on solemn occasions would he let it go, as happened at the time of the Jesuits’ visit.

Sangay, our guide, adds, by the way, this delightful detail: “The Portuguese priests even measured the Shabdrung’s goatee.” As for the mane, “it was almost two cubits long,” and the monarch had the greatest pride in it. In fact, Cacela reminds us that all Bhutanese cherished long hair, for “they have it for insignia of grandeur.”

Today, contrary to what happens in the different parts of the vast Tibet, especially among the kampas of the Kham region, Bhutanese with long hair are very rare. Shabdrung would have confessed to the priests that he intended to cut his own and to retreat to a monastery as soon as he had children to leave the throne. In fact, the Bhutanese king was to withdraw from political life shortly after the departure of the priests, staying in the monastery of Punakha where he would remain until his death in 1651. The news of his death would be kept secret for about 50 years, as the authorities sought reincarnation, and especially because they feared that the country would fall into chaos again.

Follow

Follow