Joaquim Magalhães de Castro

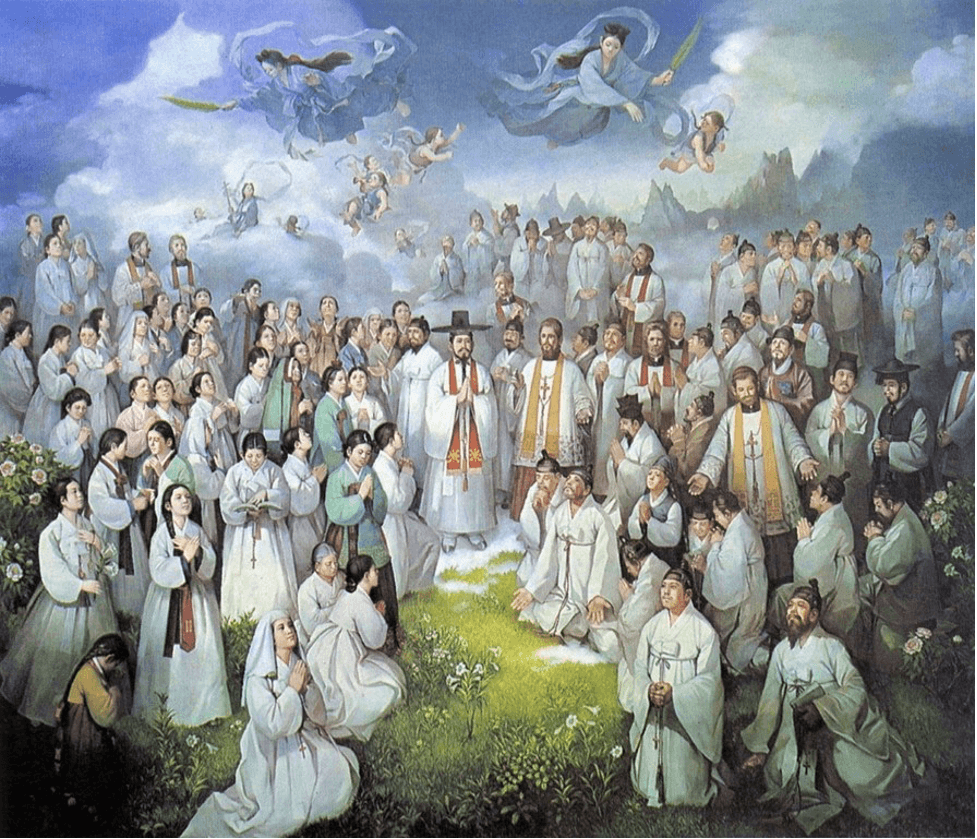

On Saturday July 5 marks the centenary of the Eucharistic liturgy celebrated on July 5, 1925, in St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican, during which the first Korean martyrs were proclaimed blessed. We are talking about 79 Catholics who suffered martyrdom, ‘in odium fidei’, in the name of their faith during the infamous persecutions of Gihae (1839) and Byeong-o (1846). Among them was the first Korean Catholic priest, Andrew Kim Taegon, who completed his academic training in Macau and later managed to enter Korea as a missionary. However, thirteen months after his ordination, he was put to the sword in 1846, at the age of 26. He is now recognized as the patron saint of the Korean clergy.

There were five major persecutions against Christians in Korea during the 19th century: in 1791, 1801, 1839, 1846 and 1866, during which between eight and ten thousand Christians perished. Religious freedom would not be granted until 1895.

The Catholic persecution of 1866, known in Korea as the ‘Byeong-in Persecution’, refers to the large-scale persecution of Catholics that occurred in Joseon in 1866 under the regency of Heungseon Daewongun, during the third year of King Gojong’s reign. The persecution would last for six years (until 1872), during which more than 8,000 lay people and numerous missionaries from the Paris Foreign Mission Society were executed. Father Félix-Clair Ridel (1830–1884)—who had earlier left Joseon to escape Daewongun’s persecution—reported the news of the martyrdom of nine French missionaries to Admiral Pierre Gustave Roze, commander of the Far East Fleet in Tianjin. Roze refused the Qing Dynasty’s offer of mediation and led three warships, intending to retaliate with the greatest force. The warships sailed past Mapo (Yanghwajin) and Seogang in late September 1866, attacked Ganghwa Island, and plundered it before withdrawing in November of that year. Furious at the incident, Heungseon Daewongun is reported to have said, “It is only right to wash away the land that Western barbarians have contaminated with the blood of Western scholars,” and set up a death camp at Jamdubong, near Yanghwanaru, where he proceeded to execute Catholics. Thousands of them died there. The severed heads of the unfortunates were thrown into the Han River, “piling up in heaps; and the water of the Han River turned blood-red.”

To commemorate this week’s event, the Martyrs’ Memorial Committee of the Archdiocese of Seoul is planning a series of events, beginning with a Eucharistic celebration on July 5—presided over by Archbishop Jeong Sun-taek—at the Seosomun Martyrs’ Shrine, the church built on the site where the executions were being carried out. A total of 41 of the 79 martyrs beatified in the Vatican on July 5, 1925, died at that site, considered “the largest site of martyrdom in the Korean Church.”

At the end of the Mass, “data on the persecution of Gihae and Byeong-o” will be presented. This report contains official data and documents relating to the persecutions from the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty, the Royal Secretariat Gazette and the Military Affairs Bureau. It was compiled based on communications and reports exchanged between the Ministry of Justice and the Police Department. This distinguishes it from existing historical materials, as it focuses almost exclusively on the testimonies of those who lived at that time. In addition to the original texts, the study also includes translations into contemporary Korean, making it easier for researchers to consult the collection.

To conclude the initiatives, an exhibition entitled Anima Mundi will be inaugurated on the evening of July 5. Anima Mundi is also the name of the section of the Vatican Museums that brings together the legacy of the World Missionary Exhibition that Pope Pius XI wanted to create in the Vatican Gardens on the occasion of the Jubilee of 1925.

Born in Yangban, Andrew Kim Taegon saw his parents martyred for practicing Christianity, an activity that was absolutely forbidden in a strongly Confucian Korea. After being baptized at age 15, Kim studied at seminaries in Macau and the Philippines, where he is now greatly revered. Ordained a priest in Shanghai in 1844 by the French bishop Jean Joseph Jean-Baptiste Ferréol, he would return to Korea to preach and evangelize in places where one could only practice the faith in secret. Kim was one of many thousands executed during this period. In 1846 he was tortured and finally beheaded near Seoul on the Han River. These were his last words: “This is the last hour of my life, listen to me carefully: if I have communicated with foreigners, it is for the sake of my religion and my God. It is for Him that I die. My immortal life is about to begin. Become a Christian if you want to be happy after death, because God has eternal punishments in store for those who refuse to know Him.”

Follow

Follow