Joaquim Magalhães de Castro

Read by an increasingly broad and diverse audience around the world, Japanese manga has long held an enormous fascination among young and old alike. In addition to the unusual superhero adventures, this peculiar type of comic book, conceived in its own format, also portrays stories of ordinary men and women. In this way, countless episodes of Japanese history have been transmitted to school-age children; and now, the trend seems to extend to a type of character who, even under fierce persecution, remained firm in their faith in Christ: we are talking about the so-called Japanese “hidden Christians”. A phenomenon that originated in the 17th century, when Christianity – introduced with immense success in the Japanese archipelago a century earlier, thanks to the continued work of missionaries from the Portuguese Patronage of the East – was expressly prohibited, with all missionaries present there being ordered to be expelled. Many of them, for refusing this order, would later be martyred, and, even under torture, they never renounced their faith.

Without priests and churches, the Japanese neophytes soon found alternative forms of organization: the village chief led the community, established religious ceremonies according to the liturgical calendar and safeguarded the sacred books; the catechists taught the children; those who knew the baptismal formulas administered the First Sacrament; and there were always some messengers who visited families to announce Sundays, Christian festivals and days of fasting and abstinence.

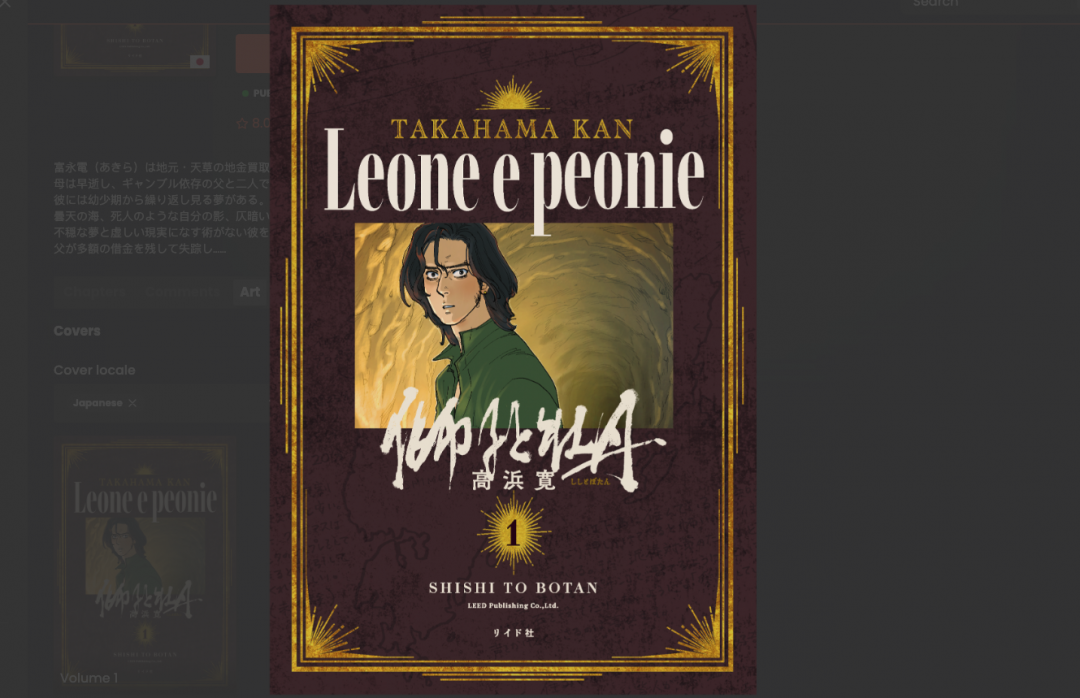

The design of the aforementioned comic strip is the responsibility of cartoonist Kan Takahama, who hopes to pass on to new generations “the treasure of a testimony of faith that occurred centuries ago, of which only a few traces remain in historical documents”. Kan Takahama recently presented his project in Italy (from 17 to 20 March) as part of a series of conferences organized by the Japanese Embassy to the Holy See and the Archdiocese of Lucca, an initiative included in the celebrations of the 440th anniversary of the “Tensho Embassy”. The name of this embassy has to do with the Japanese calendar of the time, that is, the tenth year of the Tensho Era. In fact, in March 1585, a Japanese delegation was officially received in Rome for the first time by the Pope.

The idea of sending Japanese representatives to Europe came from Alessandro Valignano, an Italian Jesuit who had been involved in missionary work in the Far East since 1573. Valignano selected two boys from the largest families of Christian daimyo at the time. The daimyos, powerful feudal lords, ruled Japan from the 10th century until the beginning of the Meiji period (mid-19th century) thanks to their vast estates. The two young men would be joined by a small group of religious people, including the Portuguese Jesuit priest Diogo de Mesquita, who would serve as guide and interpreter. With this trip, which lasted a total of eight years (1582 to 1590), the Portuguese Padroado do Oriente intended to raise awareness in the European church of the time about the Japanese reality, thus combating certain pre-established stereotypes.

Diogo Mesquita (1551-1614), superior of the College of Nagasaki, introduced Western plants to Japan, great defender of the admission of native clergy and author of more than 25 letters on Japanese reality, was a native of Mesão Frio, diocese of Lamego.

The artist Kan Takahama is from Amakusa, the place where, in 1591, the Society of Jesus founded a college for the training of Japanese clergy and where the young men of the ‘Tensho Embassy’ would continue their studies after their return to Japan, thanks to the ‘Gutenberg press’ they brought with them from Europe. Thanks to her, books with Christian themes would be printed in Japan.

The Amakusa region, like the Nagasaki region, which for 250 years have been places of refuge for persecuted Christians, are now recognized by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites.

Kan Takahama accidentally discovered old documents relating to the persecution of Christians in his home. In addition to deciphering and studying them, the artist also collected local oral traditions. This would be the basis for the work “Shishi to Botan” (“Lion and Peonies”), now also published in Italy. This book is inspired by true events; notably in the 1638 revolt of oppressed Christian peasants led by the Christian samurai Amakusa Shiro, a revolt that was violently suppressed.

But how can historical research be translated into the aesthetics of manga? This was precisely one of the questions addressed in the lectures given by Kan Takahama on March 17 and 18 in Rome (at the Pontifical Gregorian University and the Pontifical Salesian University) and on March 20 at the the Archbishop’s Residence in Lucca.

Follow

Follow