– Anastasios

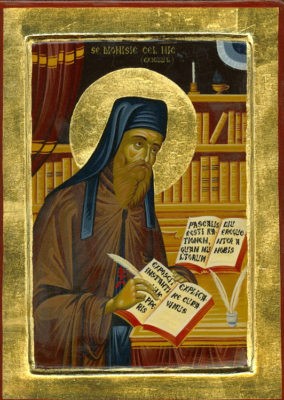

Let us talk here of a fellow student of the famous Cassiodorus, Dionysius Exiguus (means “the short one,” 470-544) a monk who was famous for some peculiar reasons. Cassiodorus had a great opinion about him, acknowledging him as very knowledgeable in the Greek and Latin languages, faithful to traditions and of great humility. He was active in Constantinople and Rome and some scholars agree that his Roman time was very influential for his formation. To him is given the responsibility of the introduction of the notion of Christian Era, Anno Domini and the computation of the years from the birth of Christ, even if some scholars dispute his calculation as entirely accurate: “In chronology Dionysius has left his mark conspicuously, for it was he who introduced the use of the Christian Era according to which dates are reckoned from the Incarnation, which he assigned to 25 March, in the year 754 from the foundation of Rome (A. U. C.). By this method of computation he intended to supersede the ‘Era of Diocletian’ previously employed, being unwilling, as he tells us, that the name of an impious persecutor should be thus kept in memory. The Era of the Incarnation, often called the Dionysian Era, was soon much used in Italy and, to some extent, a little later in Spain; during the eighth and ninth centuries it was adopted in England. Charlemagne is said to have been the first Christian ruler to employ it officially. It was not until the tenth century that it was employed in the papal chancery (Lersch, Chronologie). Dionysius also gave attention to the calculation of Easter, which so greatly occupied the early Church. To this end he advocated the adoption of the Alexandrian Cycle of nineteen years, extending that of St Cyril for a period of ninety-five years in advance. It was in this work that he adopted the Era of the Incarnation” (Gerard, J. “Dionysius Exiguus.” In The Catholic Encyclopedia. New Advent: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05010b.htm).

James A. Veitch, in an article called “Dionysius Exiguus” (in www.westarinstitute.org) commented on the controversies surrounding Dionysius: “When, in 527, he formalized the date of Jesus’ birth, Dionysius put Christmas on the map. Jesus was born, he declared, on December 25 in the Roman year 753. Dionysius then suspended time for a few days, declaring January 1, 754 – New Year’s day in Rome – as the first year in a new era of world history. With a stroke of ingenuity Dionysius had managed to shift the attention of the church from Easter to Christmas. From this point in time it seemed only logical to celebrate the birth of Jesus before his death. If Jesus’ death by crucifixion had made possible salvation for all people everywhere, so the argument went, then his birth was the sign that God was identifying with human kind by taking human form. But Dionysius made a mistake in his calculations. Perhaps he had never read the gospel account of the birth of Jesus. In Matthew Jesus is said to have been born while Herod was still King (2:1). That would translate into 4 BC (or even earlier) according to the calculations of Dionysius. As a consequence, for Christians the year 2000 is not two thousand years after the birth of Jesus, but more like 2004. That was not his only mistake. Dionysius followed the convention of his times and, as the Roman calendar moved from the year 753 to 754, he called the latter “year one” of the New World order – anno domini the year of our Lord. The concept of naught [“zero”] didn’t come into Europe from Arabia and India until about two hundred years later. As a result, centuries end with naught and begin with the digit one. So for us the year 2000 is the end of one millennium but it is not the beginning of the next: that will occur in 2001. Later, when Pope Gregory tidied up the calendar on 24 February 1582, the calendar lost eleven days. To synchronise the calendar of Dionysius with the movement of the sun, October 4 became October 15, and to avoid having to make further adjustments a leap year was introduced. Pope Gregory must also have known of the mistakes made by Dionysius but all he did was to confirm them, perhaps hoping that no one would notice.” Even if these mistakes will be certainly not of secondary importance we must admire the scientific courage of this monk who tried to figure out such an important issue with the notions available at his time.

Follow

Follow