– Aurelio Porfiri

Sometimes I come to think about how it is a privilege to be able to live in certain cities rich in history and spirituality. Although our times are extremely secularized, we cannot deny that some cities have a particular spiritual charge. Think of the emotion of a few days ago due to the fire in the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris, when thousands of French citizens took to the streets to unite their hearts with those of so many in the world who saw flames engulfing not only an artistic masterpiece, but also a sign of the faith of many generations. We also think of Jerusalem, a city that brings together the faithful of different religions. But let us also think of Rome, where one can walk on roads traveled by saints and martyrs, the Christian Rome of the many churches with their domes. The Rome of early Christianity. Sometimes critical voices are heard about the role of Rome in Catholic life, and we certainly cannot hide the fact that we live today in very complex times for the Catholic Church. Yet it cannot be forgotten that St Peter and St Paul shed their blood right there, the seat of the largest empire that ever existed. We cannot also forget that what is considered the first gospel, that of Mark, was probably written right here in Rome, perhaps under the impulse of St Peter.

It is apparent that St Mark was not a direct disciple of Jesus, although some refer to him as the boy wrapped in the sheet that followed Jesus after his arrest. But we know, as reported in the Acts of the Apostles, that he was in close relationship with St Peter and St Paul even during their Roman sojourn. We find testimony of this in various passages, reported here by an introduction to the Gospel of Mark contained in an internet site belonging to the Italian Episcopal Conference: “Paul mentions Mark three times in his letters…. While writing to the Colossians, probably from Rome in the year 61 AD, Paul also sends greetings to Mark: ‘Aristarchus, my fellow prisoner, greets you, and Mark, Barnabas’ cousin, about whom you have received instructions: if he comes from you welcome him’ (Col 4:10). In the same circumstance Paul also sends a note to Philemon and, in the list of collaborators, also mentions Mark: ‘Epaphras, my fellow prisoner for Christ Jesus, with Mark, Aristarchus, Demas, and Luke, my collaborators, greets you’ (Philem 24). Finally, in his last letter, shortly before his martyrdom, around the year 67 AD, Paul asks Timothy, who resides in Ephesus, to come and see him in Rome, bringing with him also Mark, a sign that he is no longer present in the capital: ‘Only Luke is with me. Take Mark and take him with you, for he will be useful to me for the ministry’ (2 Tim 4:11). Finally, the name of Mark appears in the first letter of Peter, also written by Rome around the year 65 AD, where he is a close associate of the apostle: ‘The community that has been elected like you and dwells in Babylon greets you; and also Mark, my son’ (l Pt 5:13).”

His Gospel has been said to have an almost cinematic narrative approach. He was addressing the pagans, the Romans, who would not have been moved with spiritual speeches, but better convinced with examples and a little healthy action: “The narrative that the evangelist Mark makes will surprise you from the first lines: it will drop you like in a movie in the life of Jesus starting from the preaching of John the Baptist to the river and from the baptism of Jesus himself. Written basically for the pagans and for those who did not know the customs and traditions of the Jewish people, the text is rich in comments on places, customs and words, explanations on the meanings of words and Jewish customs, and this fact makes the images even more concrete and tangible before the eyes of the reader. Moreover the author insists more on the actions of Jesus than on his teachings: even if there are recurrent words like ‘to teach’ and ‘to preach,’ Mark reports only four parables (in chapter 4), while he recounts eighteen miracles” (bibbia.it).

Papias, bishop of Hierapolis (second century), tells us of Mark: “To what the presbyter said: Mark, Peter’s interpreter, wrote with precision, but without order, all that he remembered of the words and deeds of Christ; for he had not heard the Lord, nor had he lived with him, but later, as I said, he had been Peter’s companion. And Peter imparted his teachings according to the opportunity, without the intention of making an orderly exposition of the Lord’s sayings. … Mark, writing some things as they came to mind, worried only about one thing: not to leave out nothing of what he had heard and not to tell any lie about it.”

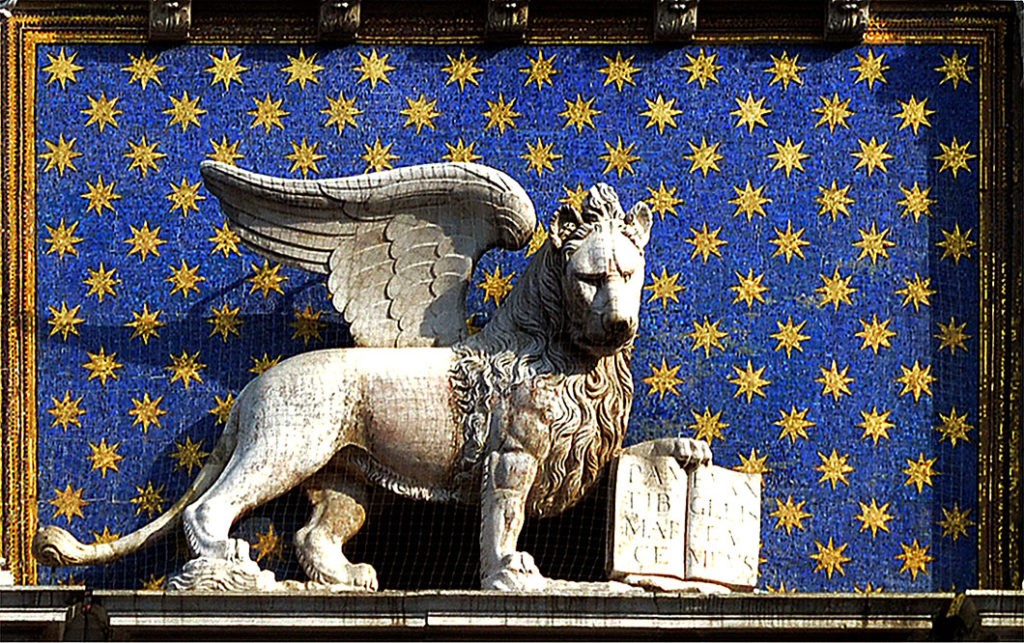

The symbol used to represent Mark is that of the winged lion. With this symbol he is also represented in the city of Venice, of which St Mark is august protector. The lion is a symbol of courage and strength, its roar imposes its authority over those who dare to challenge it. This does not seem to us to be a symbol of the Church, at least of how the Church should be. Too often we think that a vague idea of love in the form of a vague concept of mercy can truly represent the action of the Church in the world. Yet Jesus showed his mercy precisely in his justness and in calling things by their name, good was called “good” and evil was called “evil.”

Here is a beautiful passage from the Gospel of Mark where we observe the Lord’s modus operandi: “He entered the synagogue again. There was a man there who had a paralyzed hand, and they watched him heal him on the Sabbath day to accuse him. He told the man who had his hand paralyzed: ‘Get up, come here in the middle!’ Then he asked them: ‘Is it lawful to do good on the sabbath or do evil, save a life or kill it?’ But they were silent. And looking at them all around with indignation, saddened by the hardness of their hearts, he said to the man: ‘Hold out your hand!’ He held it out and his hand was healed. And the Pharisees immediately went out with the Herodians and took counsel against him to kill him.” As we observe, Jesus does not look for dialogue as the privileged method, but for dispute. He challenges his interlocutors in order to convince them of the accuracy of his message.

“With judgment, the subject does not limit himself to enunciating a state of affairs (‘Things are like that’), but he also affirms the truth, in the sense that he also says that ‘it is true that things are like this’ and that ‘it is not true that things are different.’ Said in another way, with the judgment it is affirmed that that determined thing must be thought of in this way and that the opposite is unthinkable.” (Antonio Livi, Filosofia del senso comune, 2018).

We must always be very careful not to judge things starting from ourselves and from our supposed righteousness. It is true that we must not judge, so as not to be judged. But when the rights of the truth of things are affirmed, we are not the ones to judge, but we are all judged by the truth itself which is outside of us and which is objective. Cardinal Carlo Caffarra observed: “In essence, when a man seriously wonders whether or not there is a truth about man, whether the design of his own existence is necessarily confronted with a meaning or purpose that precedes and judges the design itself or everything is exclusive creation of man: then, at that moment, in the heart of that man, the Gospel of life is clashing with the culture of death. The Word, having become man, testifies to this truth and the man, in whose heart the culture of death has already sown his trap, says: ‘And what is the truth?’ Faith and unbelief: faith as assent to the Truth – disbelief as a departure from the Truth. It is the first act of the clash that takes place in the heart of every man, between the Gospel of life and the culture of death” (Vangelo della vita e cultura della morte, 1992).

Behold, the Gospel of Mark, like the other canonical writings, must for us be the banner of that Gospel of Jesus Christ the Lord who, let us not forget, did not appear primarily as mercy, goodness and meekness (which were certainly in Him, but as consequence), but as way, truth and life.

Follow

Follow