– José Maria C.S. André

A hundred and twenty-one years ago, the lawyer Secondo Pia photographed a long blanket, 4.5 by 1.5 meters, safeguarded in the cathedral of Turin as a relic. After many troubled historical events, the House of Savoy became the owner of the blanket, and when the capital of the duchy was transferred to Turin, in the 16th century, this piece was also taken there.

Secondo Pia set up his photographic box in front of the blanket and focused its lenses. Working in the dark, he placed a glass plate covered with a photochemical emulsion in the box and, when everything was ready, uncovered the lenses. The light reflected from the blanket burst through the lenses, focused on the glass slide, and burned the emulsion. After an appropriate exposure, for the emulsion to be burned in the light zones, the plate was removed in the darkness, to be washed with chemicals and thereafter rendered insensitive to light.

Until a few years ago, photographs were made this way, in two phases. First, the photographic film would be darkened by light to give a “negative,” i.e., an image with inverted colors: the bright parts in dark and the black parts in white. In the second stage, the “negative of the negative” was produced, recovering the intended image. The result of the double inversion was the “positive” and the film used in the intermediate step was the “negative.”

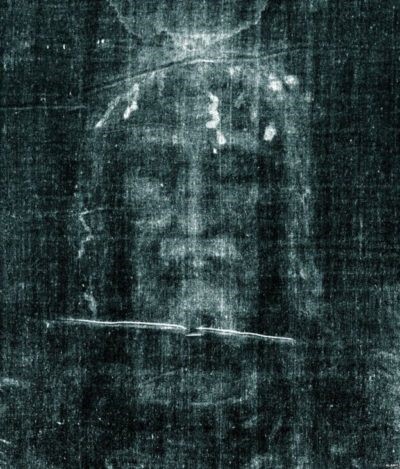

When Secondo Pia observed the result of the first stage, he discovered, to his surprise, that he already had before him the natural, the “positive” image! This meant that the image of the blanket was a “negative.”

Till the invention of photography, no one had the idea of painting the “negative” with colors in reverse, making the images unrecognizable. It was the primitive photographic technique that created this instrumental and intermediate stage, as a means to obtain the original image. How was it formed, in a linen blanket with almost two thousand years of history, guarded and disputed with so much commitment throughout the centuries, a negative image that only the photography of our days manages to reveal?

The figure of this blanket is the corpse of a strong man, six feet high, covered with wounds. His head was marked by bloody punctures. The knees, and nose injured, as if he suffered a violent fall. A sore wound on his chest. His wrists and feet pierced with nails, his back scourged and his shoulders hurt, as if he had carried the heavy beam of a cross.

This photograph takes us back two thousand years, at the time when Joseph of Arimathea and others asked Pilate for the dead body of Jesus and, having taken Him off the Cross, wrapped Him in a fine linen blanket and set it in a new sepulcher, excavated in the rock. The Jews set up a guard but three days later, on Sunday, very early in the morning, when the first comers arrived at the tomb, the body was no longer there.

The Resurrection of Jesus reveals to us what his Death did not allow us to see. Like a dazzling negative, like the triumph of truth.

Follow

Follow