– Rev José Mario O Mandía

We often talk about mysteries and dogmas. What do we mean by “mystery”? And what do we mean by “dogma”?

Let’s take up mysteries first.

In ordinary language, a mystery is something that we cannot fully understand or explain, something whose cause or causes we don’t fully know. In this sense, we find many mysteries in nature. Indeed, despite the advancement of science, there are still many things we still do not know about the world and the universe.

In theology, however, mystery is defined as a truth that (1) pertains to the supernatural order and (2) cannot be known if God does not reveal them to us.

From this definition, we can say that the existence of God and the existence of the soul are not “mysteries” because (as we have shown previously – see Bite-Size Philosophy 3), these can be known through reasoning. Without having recourse to Sacred Scripture or Church teaching, a man can discover that there is a soul, and that there is a God, though his knowledge of the soul or of God may be limited.

Knowing that we have a soul and that God exists is important, but there is much more we need to know. This is why God tells us the truth about the world, about ourselves and about Him. This is what we call Revelation. Through Revelation we get to know the mysteries of our Faith.

How about dogmas?

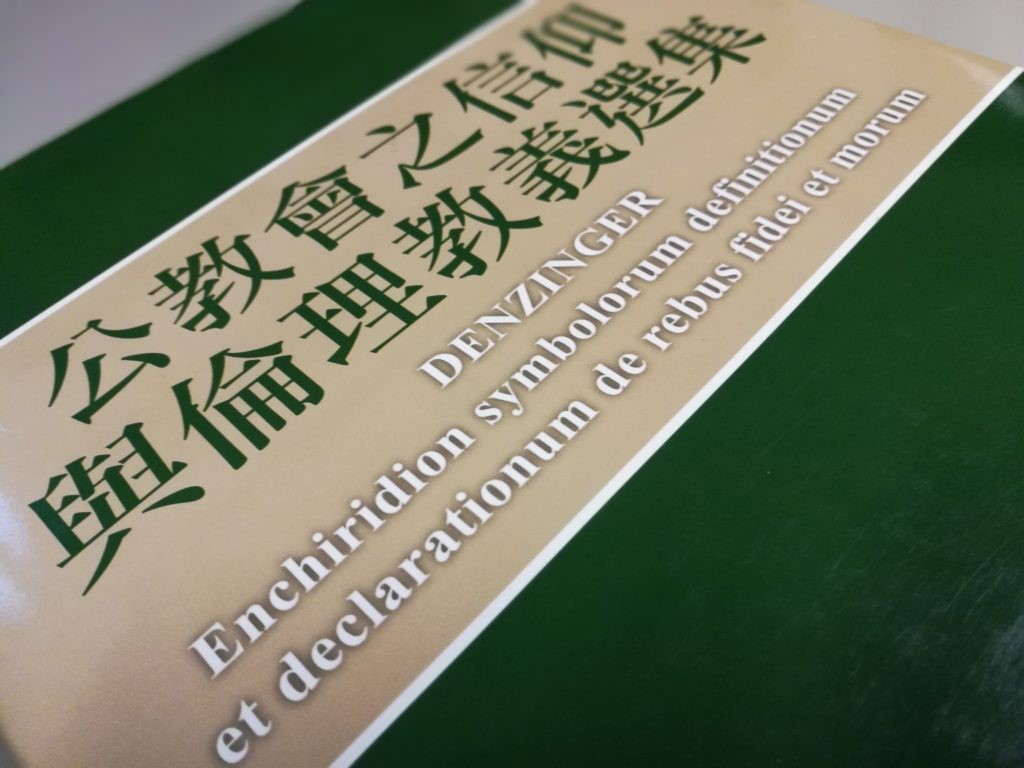

Dogmas come from the Church, who has been given the responsibility and the grace of safeguarding and transmitting what God has revealed (the contents of Revelation).

The Catechism (no 88) teaches: “The Church’s Magisterium exercises the authority it holds from Christ to the fullest extent when it defines dogmas, that is, when it proposes, in a form obliging the Christian people to an irrevocable adherence of faith, truths contained in divine Revelation or also when it proposes, in a definitive way, truths having a necessary connection with them.”

How do we know when the Church “defines dogmas”?

It is possible to know this from the language that the Church uses in a document. Let us take a relatively recent example: the Declaration Dominus Iesus, published on 6 August 2000. It does not define any new doctrine, but reiterates the importance of certain dogmas. Two important phrases are repeated throughout the document: “it must be firmly believed that …” (6 times) and “… is contrary to the Christian/Catholic faith” (8 times). When it speaks in this way, the Church teaches unequivocally and without hesitation that a particular teaching has been revealed by God (through Scripture and Tradition), is thus confirmed by the Magisterium, and must be believed by anyone who considers himself a “believer.”

In the Creed we can find many of the major dogmas that have been defined in the past by the Church. For a more extensive version, check out the Athanasian Creed.

It is not enough to believe, however. “Even the demons believe – and shudder” (James 2:19). What child would tell his mom he believes her and yet does not do what she asks? This is why the CCC (no 89) adds: “There is an organic connection between our spiritual life and the dogmas. Dogmas are lights along the path of faith; they illuminate it and make it secure. Conversely, if our life is upright, our intellect and heart will be open to welcome the light shed by the dogmas of faith (cf John 8:31-32).”

Belief is only the beginning of the journey. To live a Christian life means to know, love and serve God. The better we know God, the better we can love and serve Him in the way that He wants to be loved and served.

Follow

Follow