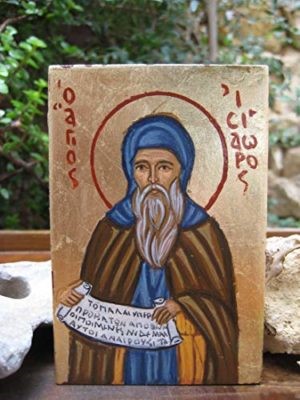

– Anastasios

This saint is not well known as other Church Fathers, so it will be good to say a few things about his life. He was born in Alexandria around 370. He gave away everything he had to the poor to withdraw near the city of Pelusium and live a life of prayer and study. He was considered as a father by Cyril of Alexandria and was a disciple of Saint John Chrysostom, was ordained a priest and was abbot in his community. He died around the year 440.

He was a great exegete of the Bible and we have thousands of his letters. Some excerpts (translated by Edward Campbell and available in https://www.roger-pearse.com/weblog/tag/isidore-of-pelusium/): “If you have been injured by words and given way to unrestrained anger, how can you become a worker in the Lord‘s Vineyard? For He determines that whosoever, struck on one cheek, is capable also of presenting the other, is that one who ‘bears the oppressiveness of the day and its heat’ and who thus will have accomplished all the labor of the Lord’s command. For if you aspire to those greater rewards, do not be distraught at the lesser toils, but learn to bear with love the greater ones, for you will not otherwise receive a penny unless witnessed to by the perfection of (your) own efforts” (to Frontinos the Monk). Isidore is telling both Frontinus and us the great value of those that can accept suffering and injustice in the name of the Lord. This does not mean that we have to favor injustice but that we need to fight for justice for its own sake and not because our pride was wounded.

In a letter to Duke Gelasios, he returned to some of these concepts: “It is usual for human beings – at least for most, although foreign to divine legislation, to be puffed up by (noble) descent, practical wisdom, possessions, beauty or rank. However it helps in no way the pride of those who are from earth and who again return to it. That you possess none at all of these qualities you will scarcely deny. If then you are deprived of all the things that cause one to swell and be puffed up, since you are of lowly extraction, poor, of weak intellect, [very] ordinary and ill-shaped, why do you strut through the city, as though you were the most reputed of all, and become the author of many disturbances there? Rather get to know yourself and acquire a manner proportioned to your insignificance, or alternatively prepare yourself for efforts and dangers, with which those in power will reward you. For you are lacking in wealth, which frequently smoothes over the asperities of circumstances and the blows of fate.” Isidore warns us to be vigilant in this regard.

To a new monk called Theognostos he wrote: “You have grasped the ploughshare well and to the point. You are succeeding in escaping from suffocating matter. You have stepped forth well towards a higher citizenship. Stand therefore wide awake as a heavy-armed soldier, lest sleep slip in rendering you flabby and show you up as a deserter, which God forbid. For we are not unaware of the designs of the Evil One.” This concept of the “good battle” for God is represented here, because the world is set as a stage for the fight between good and evil.

About him was said: “His letters addressed to persons following the religious life afford many important clues which enable us to form a fairly exact idea of the intellectual standard then existing in Egyptian monastic centres. Isidore reproaches the monk Thalelæeus with being interested in reading pagan historians and pagan poets which were full of fables, lies, and obscenities capable of opening wounds that had healed and of recalling the spirit of uncleanness to the house from which it had been ejected. His advice with regard to those who were embracing the monastic state was that they should not at first be made to feel all the austerities of the rule lest they should be repelled, nor should they be left idle and exempt from ordinary tasks lest they should acquire habits of laziness, but they should be led step by step to what is most perfect. Great abstinences serve no purpose unless they are accompanied by the mortification of the senses. In a great number of St Isidore’s letters concerning the monastic state it may be remarked that he holds it to consist mainly in retirement and obedience; that retirement includes forgetfulness of the things one has abandoned and the renunciation of old habits, while obedience is attended with mortification of the flesh. A monk’s habit should if possible be of skins, and his food consist of herbs, unless bodily weakness require something more, in which case he should be guided by the judgment of his superior, for he must not be governed by his own will, but according to the will of those who have grown old in the practice of the religious life.” (Leclercq, H. “St. Isidore of Pelusium,” In The Catholic Encyclopedia: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08185c.htm).

He was another great example of the great era of the Fathers in the Egyptian desert.

Follow

Follow