– Aurelio Porfiri

There is a book by Antonio Rosmini that perhaps few people know, partly because the production of the great scholar from Rovereto is huge and it is not possible to know everything. This book is called History of Impiety (Storia dell’empietà) and is a controversy with the French philosopher Beniamino Constant (1767-1830), accused of making religion a mere product of sentiment. In fact, the danger identified by Rosmini is not of secondary importance. We could say that today it is a problem that seems even more important. Indeed, is not religion often perceived as the product of what I feel, of what I elaborate within me? But in this way religion becomes a subjective fact, a personal feeling, a mere opinion. But this does not fit well with the announcement brought by Jesus Christ with his definitive claim to be the Way, the Truth and the Life. Truth, just to name one, cannot be reduced to an opinion, perhaps also respectable, but certainly not definitive. And if we commit our life completely to something, if we pray incessantly, we attend ceremonies frequently, we observe certain behaviors that engage us every day, certainly we do not want these to be based on a human opinion, on a vague religious sentiment.

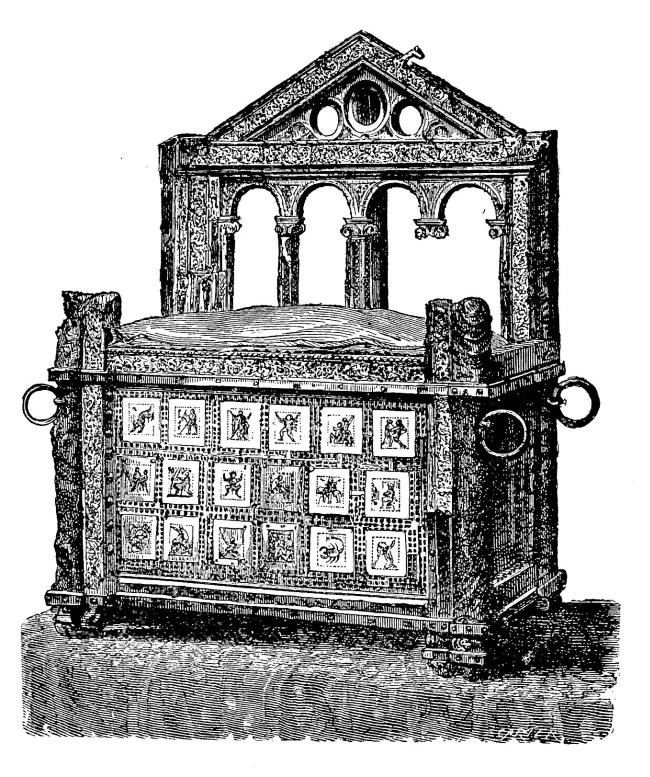

This is why we need to reflect on a feast like that of the Chair of St Peter, which the Church celebrates on February 22nd. The Chair is a sign and symbol of teaching power, a sign of those who have the power to transmit knowledge with supreme authority. A knowledge that is not human, which therefore, must be preserved, transmitted, deepened, but not manipulated or adapted to the tastes of this or that audience.

The online magazine sanfrancescopatronoditalia.it explains the origin of the feast: “How did the veneration for the Chair of Peter come about? An interesting thesis is explained by Father Umberto Fasola, a Barnabite and scholar of Christian archaeology. In the ancient documents we find the story of a pilgrim from Monza who wanted to bring to his Queen Teodolinda at the end of the 6th century the sacred oils collected on the graves of the martyrs. He set off in the region between the Salaria and the Nomentana [in Rome] to look for the remains of Peter. Why not in the Vatican? Following texts that intersect with the legend, it is clear that at that time there had to be an object that attracted popular devotion. Fasola, thanks to the texts, identifies it with a sedes or chair of St Peter. How was the legend born? For Fasola it was important to study it to understand the nature of the feast of 22 February, formerly called Natale Petri de Cathedra. During the excavations of the late 1800s in the Major Cemetery on Via Nomentana it seemed clear to scholars, not without controversy, that a memoria Petri was revered from the earliest centuries of Christianity. And the discovery of some ‘cathedrae’ in stone with evident signs of veneration seemed to confirm this idea. On the date, however, there is still mystery. On February 22nd in the pagan world the Parentalia days dedicated by the relatives to the dead, ended. And in the cemeteries there were the refrigeria, the funeral banquets, real parties. The liturgical feast defined in 336 in the Depositio Martyrum did not refer to a material chair, but certainly the solemnity recalled the object. In short, an interweaving of popular devotion and theology that was concretised, perhaps, in the ‘cathedrae’ that are found in the catacombs born with other purposes, precisely for the refrigeria. The faithful who went to pray for their relatives on the day when the party was defined, in front of a ‘cathedra,’ think of Peter.”

In a speech to the Pontifical Council for the Family in 1985, Cardinal Carlo Caffarra said: “The Church’s reason for being is one: to guide man to eternal communion with God.” Precisely this supernatural purpose requires a Magisterium that is not at the mercy of changing human opinions, but is anchored to an eternal truth, a deposit that the Church guards and interprets but does not change. Again, Cardinal Caffarra, in an article for the Osservatore Romano (1976) observed: “The permanence of the apostolic depositum in the Church that lives in it, is ensured by the apostolic succession entrusted with the task of authentically interpreting the written or transmitted Word of God. And so this last element of transcendence in history accomplishes its structure so that the Truth and the Law of Christ are given to man through a ‘constellation’ of three magnitudes inseparably joined together: Holy Scripture – Tradition – Magisterium. To think of attaining the Revelation of God in Christ transmitted to us by the Apostles on another path outside the one indicated by that constellation is to go in the wrong direction (see S Irenaeus, Adv. Haer IV, 26, 2).”

This teaching function of the Church is today often under attack by forces external and internal to the Church herself. Today one thinks that judging is out of place, precisely because everything is reduced to the sentiment of the religious and therefore in a relative sense valid for those who support that kind of feeling. Monsignor Antonio Livi, a foremost Catholic philosopher, in one of his most important books (Filosofia del senso comune, 2018) stated: “With judgment, the subject is not limited to enunciating a state of affairs (‘This is the case’), but also affirms its truth, in the sense that he also says that ‘it is true that things are like this’ and that ‘it is not true that things are different.’ In another way, with the judgment it is stated that this particular thing must be thought of as such and that the opposite is unthinkable.” And if this is true for a common judgment the more true it is for the informed judgments of supernatural truths as those that are given by those in charge of the Catholic Church, in the person of her Supreme Pastor, the successor of Peter, the Pope.

Today this magisterial power is strongly questioned and undermined in various ways. One is the recourse to the category of “pastoral” as the interpretative criterion of everything. Msgr Livi notes: “Since John XXIII we have the idea that the Church’s pastoral work consists in translating the dogma into an understandable language, acceptable to modern man – something that is a myth, a fantasy – and in finding the good even in the theoretical positions most contrary to the dogma. I believe that it is a concept of “pastoral” which, as such, is erroneous and harmful to the Church, but as a theory it is an activity, an erroneous practice which, as a doctrine, has no support in infallibility. The practice can be erroneous because it is an act deriving from a prudential judgment that can be judged erroneous by those who express other prudential judgments, such as mine, which are judgments not supported by infallibility. So, when I criticize this “pastoral” that seems disastrous to me, I use judgments, adjectives and adverbs that make it clear that these are my opinions. God will judge, but there is nothing dogmatic about judging the opportunity of a pastoral line. Those who do harm to the Church are those who dogmatically consider the “pastoral” of the Council and the popes following it as the only one necessary, and speak of “new Pentecost of the Church” and “interventions of the Holy Spirit,” as if these prudential judgments , which I consider erroneous, were instead dogmatically infallible and even holy and the only thing that the Church can do” (gloria.tv). So those who defend the right to every opinion transform the opinions that are more suitable for them into new dogmas, to be observed without even questioning, at the risk of incurring in excommunications in the form of isolation and civil (and ecclesial) death. In order to justify this rebellion against the authentic magisterium, recourse is made to justifications, including that of the so-called “people,” invoked to endorse opinions that are instead promoted by some and imposed on everyone. But we always talk about “opinions,” as we said above, that should be examined in comparison with the tradition of the Church. We do not follow the personal (even if respectable) opinions of this or that Pontiff, but we follow him as an authentic interpreter of the deposit of faith.

But let’s go back to the concept of “people” for a moment and read again what Monsignor Antonio Livi has to say about this: “‘We must arrive at a people’s Church.’ But the people is a purely rhetorical image. You can never know what the people want, that is, a multitude of different people. Even in politics, the expression “the people” is purely rhetorical, and even more so in theology. For example: to say that the people wanted to change the Mass is nonsense – this has never been possible or attested. Among the people there are those who, like Padre Pio in his time, are full of faith, and those who have no faith. Then there were those who wanted to reform things because the Latin Mass did not please them and they wanted it in Italian, but they did not understand the words of the Mass either in Latin or in Italian. The Church has never conducted “democratic” operations, such as electing people with the agreement of a base: it has never taken what it must teach from what people think. The Church must teach what Jesus said: it is so simple!” (gloria.tv). Of course it is simple, but it becomes more difficult when the opinion is transformed into dogma and when the real dogma is treated as mere opinion.

Follow

Follow