In the past century history has seen a strong rethinking about many assumptions coming from the Rankean tradition, that tradition established from the German historian Leopold von Ranke which demanda that history has to establish “what has really happened.”

Of course we would be all happy if history could be reconstructed faithfully but we know that too much is lost in the passing of time, and so we need to rely on reconstructions that are plausible. It is not something to be ashamed about. We cannot fight against the perils of time, we need to negotiate with our past. And also it is not less important that history is also the historian, with his or her personality, prejudices, preconceptions. We are not neutral when we write about something we are also writing a little about ourselves.

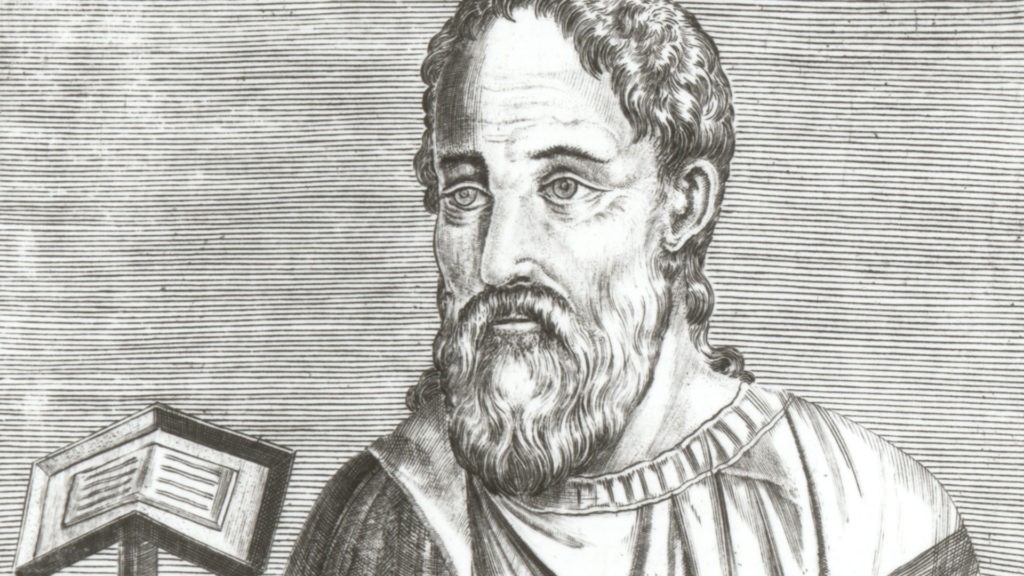

Saying that, I am not advocating that is not possible to make history and also that peculiar kind of history that is ecclesiastical history. The greatest historian in the first centuries was certainly Eusebius of Caesarea (263-339). He was a disciple of Saint Pamphilus, and as a sign of affection to him Eusebius added “Pamphilus” to his own name. In 313 (a very important date in the history of Christianity) he was made Bishop of Caesarea. He was suspected of sympathies toward Arianism, a devastating heresy of the time that stated that Jesus was not properly to be called the Son of God.

Eusebius, with all the limitations of the tools available in his time, was a great historian and we may remember some of his works such as Chronicle, Church History, Life of Constantine, Apology for Origen and others.

On June 13, 2007, Pope Benedict XVI said of him: “Eusebius strongly challenges believers of all times on their approach to the events of history and of the Church in particular. He also challenges us: what is our attitude with regard to the Church’s experiences? Is it the attitude of those who are interested in it merely out of curiosity, or even in search of something sensational or shocking at all costs? Or is it an attitude full of love and open to the mystery of those who know — through faith — that they can trace in the history of the Church those signs of God’s love and the great works of salvation wrought by him? If this is our attitude, we can only feel stimulated to a more coherent and generous response, to a more Christian witness of life, in order to bequeath the signs of God’s love also to the generations to come. ‘There is a mystery,’ Cardinal Jean Daniélou, an eminent Patristics scholar, never tired of saying: ‘History has a hidden content…. The mystery is that of God’s works which constitute in time the authentic reality concealed behind the appearances…. However, this history which he brings about for man, God does not bring about without him. “Pausing to contemplate the ‘great things’ worked by God would mean seeing only one aspect of things. The human response lies before them”’ (Saggio sul mistero della storia, Italian edition, Brescia, 1963, p. 182). Today, too, so many centuries later, Eusebius of Caesarea invites believers, invites us, to wonder, to contemplate in history the great works of God for the salvation of humankind. And just as energetically, he invites us to conversion of life.”

Let us look how Eusebius presented his work in the Church History: “But at the outset I must crave for my work the indulgence of the wise, for I confess that it is beyond my power to produce a perfect and complete history, and since I am the first to enter upon the subject, I am attempting to traverse as it were a lonely and untrodden path. I pray that I may have God as my guide and the power of the Lord as my aid, since I am unable to find even the bare footsteps of those who have traveled the way before me, except in brief fragments, in which some in one way, others in another, have transmitted to us particular accounts of the times in which they lived. From afar they raise their voices like torches, and they cry out, as from some lofty and conspicuous watchtower, admonishing us where to walk and how to direct the course of our work steadily and safely. Having gathered therefore from the matters mentioned here and there by them whatever we consider important for the present work, and having plucked like flowers from a meadow the appropriate passages from ancient writers, we shall endeavor to embody the whole in a historical narrative, content if we preserve the memory of the lines of succession of the apostles of our Saviour; if not indeed of all, yet of the most renowned of them in those churches that are the most noted, and which even to the present time are held in honor. This work seems especially important to me because I know of no ecclesiastical writer who has devoted himself to this subject. I hope that it will appear most useful to those who are fond of historical research.”

So, among his shortcomings that we all have, Eusebius in this passage is teaching that is necessary to be humble when undertaking historical (or other) work. Let us not forget this precious lesson.

Follow

Follow