Aurelio Porfiri

I happened to read an interesting article by Italian journalist, politician and intellectual Raniero La Valle, an illustrious representative of progressive Catholicism and above all of that Catholic world that considered the socialist and communist experience to be appropriate to their religious faith.

In reality, on March 19, 1937, Pius XI had already framed this problem well, when in the Divini Redemptoris he affirmed: “Communism in the beginning showed itself as it was in all its perversity, but soon realized that in this way it distanced itself from peoples, and therefore has changed tactics and endeavors to attract crowds with various deceptions, hiding their designs behind ideas which in themselves are good and attractive. Thus, seeing the common desire for peace, the leaders of communism pretend to be the most zealous advocates and propagators of the world peace movement; but at the same time they excite a class struggle that makes rivers of blood flow, and feeling that they have no internal guarantee of peace, they resort to unlimited armaments. Thus, under various names that do not even allude to communism, they created associations and periodicals which then only serve to make their ideas penetrate into environments otherwise not easily accessible to them; on the contrary, they treacherously try to infiltrate Catholic and religious associations. Thus elsewhere, without at all withdrawing from their perverse principles, they invite Catholics to collaborate with them in the so-called humanitarian and charitable field, sometimes even proposing things that are entirely in conformity with the Christian spirit and the doctrine of the Church. Elsewhere, they push hypocrisy to the point of making people believe that communism in countries of greater faith or culture will take on another milder aspect, will not prevent religious worship and will respect the freedom of conscience. Indeed, there are those who, referring to certain changes recently introduced in Soviet legislation, conclude that communism is about to abandon its program of struggle against God. See to it, Venerable Brothers, that the faithful do not allow themselves to be deceived! Communism is intrinsically perverse and no collaboration with it on the part of anyone who wants to save Christian civilization can be admitted in any field. And if some misled cooperate in the victory of communism in their country, they will fall first as victims of their error, and the more the regions where communism manages to penetrate are distinguished by the antiquity and greatness of their Christian civilization, so much so the hatred of the ‘godless’ will manifest itself more devastating.”

The encounter between socialism, communism and Christianity is one of the strands of modernism, which a few years after the encyclical of Pope Pius XI will make Ernesto Buonaiuti, one of the great protagonists of early modernism, say the following: “Who knows that from the propaganda of the godless a handful of idealists will not come out tomorrow to show men how justice and peace are introduced into the world, not through propaganda that lay their bases on the narrow and precarious interest of everyday life, but only through spiritual preaching, which they instill in man the sense of those higher ideals for which alone it is worth living and dying. On that day it will be possible to evaluate the timely function of the Catholic Communists.” In short, there was no way to convince them.

Here, the godless, as Pope Ratti says, is a bit of the theme that Raniero La Valle deals with in his blog in a post on July 9, 2021 entitled “The God we lose.” An interesting article that took its cue from the dossier edited by Enrico Peyretti on the Chiesa di tutti Chiesa dei poveri website, entitled Dossier on post-theism, in which various people expressed their opinion on this issue. Raniero La Valle seems to want to extinguish the most extreme drifts of those who would like to get rid of God and religion without too many compliments, but then he comments as follows: “Perhaps it could be said here that at the basis there is a basic misunderstanding about the content of the dispute itself: for neo-non-believers, placing the question of God in the past means rejecting its objectification that has made it a tributary of myth, fantasy, anthropomorphic invention, the ‘Immense Object’ made prey to reason; and they have the reasons. But with God thought like this, the considerations have been done for some time, the answer to the question about the identity of God is that of Jesus to the Samaritan woman, God should not be sought on this mountain or on that other, but in Spirit and truth; the question instead is that of the human relationship with him, it is faith that involves him in history, it is faith that can be identified before and after (‘When the Son of man comes will he find faith on Earth?’); the question is about the meaning and implications of the faith of those who believe in him, this is what sets history on fire.”

But it is precisely this rejection of the presence of God as objective and transcendent but only as an immanent presence that has importance only insofar as there is a human relationship with Him that moves it from its fundamental role to being an idea that we now live as a relic of the past. Here, too, modernism had already said everything, probably reacting to the Dei Filius of Vatican Council I which said: “If anyone says that the one true God, our Creator and Lord, cannot be known with certainty by the natural light of human reason, through the things that were made by him: be anathema.” That is, the knowledge of God is independent of the subjectivity of the knower who recognizes it, but does not create it.

The sentence with which La Valle concludes his article should also be amply commented: “If we lose this God [the personal God], we can add, we would also lose the nonviolent God who is the great gift given to humanity by the Church of the Council, from John XXIII to Pope Francis in Abu Dhabi to pray in the Nineveh plain, and violence, starting with the religious one, would remain inarginated.” However, all of this is understandable in the cultural landscape of the author, as the distinguished representative of progressive Catholicism.

In an article also on his blog of July 31, Raniero La Valle returns to his previous article, which had aroused a lot of attention. His opening comment raises more questions than he intends to answer: “It is not my intention nor would I be able to answer all the questions; it is beyond question that the criticism of post-theism does not ignore that we are talking about a mystery, that the only appropriate language would be the apophatic one, that mysticism is the true place of human relationship with God; therefore all the replies that insist on this are right. However, much more than this say many who support the post-theist position which, as an epochal turning point, sanctions the closing of relationships with God, seen in the perhaps somewhat stereotypical forms in which theism has handed it down (omnipotent, omniscient, despotic, etc. ).”

Does his omnipotence and omniscience form stereotypes? If He is God he can and knows everything, otherwise he would not be God. Then La Valle launches into a reasoning that has a certain organicity that begins as follows: “Therefore it is useful to ask ourselves again about the terms of the comparison, to try to clarify. Meanwhile, it must be said that what is proposed to us is not atheism, because no God has ever existed for atheism, not even this now abandoned; it is not because of the changing times that he is now denied, the privation of God is another that must be ascribed to his long and noble tradition. Post-theism argues instead of a God who was there, or who at least was believed (and so much and by many that an entire historical epoch has been characterized around this notion of God), and who now in a world that has become adult he is no longer necessary, he has no reason to be believed and to whom it is easy to put on improbable connotations today refuted to the point of mockery.” In short, post theism is not atheism, because for the atheist God does not exist, but for the post theist there was an idea of God that is no longer necessary. Everything is reduced to immanence. God exists because I create him, when I no longer need him he disappears as if he could not exist regardless of my thinking about him. In short, we are still in the good old immanentism, one of the cornerstones of modernism.

The way in which La Valle ends his second article, in which he denounced post-theism rather as a critique of monotheism, is interesting: “We must therefore be vigilant so that this ‘post’ of theism is not rather a relapse into the past and why this return to the areopagus of Athens which should free us from the ‘unknown God,’ rightly inaccessible to science, should not rather consign us to the idols that are increasingly taking control of our lives. In fact, if we have more certainties and fewer antidotes, idols grow in number and power, whether it is the glorious soccer, sovereign markets, essential patents on vaccines or the freedom to pollute.”

Here I agree with La Valle and with a phrase attributed (it seems clumsily) to Gilbert Keith Chesterton: “When people stop believing in God, it is not true that they do not believe in anything, because they believe in everything.” And to understand this, just look around.

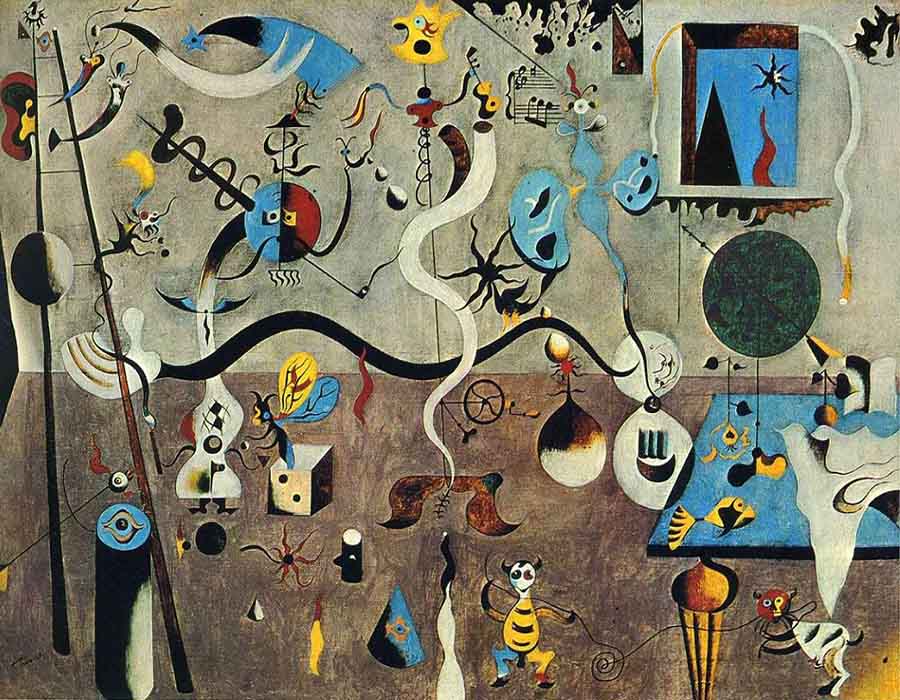

(Image: Harlequin’s Carnival (1924-25), by Joan Miro, Albright–Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo)

Follow

Follow