Aurelio Porfiri

I believe there are few musicians who have a posthumous contemporary fame like the Venetian Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741), who died 280 years ago on 28 July in a situation of near poverty and buried in a mass grave in Vienna, where he was at that time. He was then almost forgotten and revived in the past century. He was a great protagonist of the instrumental season of the Baroque, of which he embodied the merits and even the excesses.

He was ordained a priest, although it seems that in this sense he was quite peculiar, preferring the stages of the opera houses to his liturgical and pastoral duties. He was ordained in 1703 but due to poor health it seems he almost immediately obtained the dispensation from his priestly obligations to devote himself completely to his activity as a musician (and this would partially justify the above fame). He was active in various fields of composition, such as opera, but had great resonance in the field of instrumental music, especially for his concerts written for the talented students of the Ospedale della Pietà in Venice, in which he was active for many decades and for which he composed much of his music.

Alongside his instrumental and operatic production, his production in the field of sacred music was not secondary, a production still widely present today in the concert programs of various musical institutions around the world. As an example we propose the psalm Beatus Vir RV 597 (he composed various versions of this psalm) for 2 soloists, double choir and double orchestra, one of his works rightly more famous from him. The version of Psalm 111 of the “red priest” (as he was nicknamed because of the color of his hair) is a concentrate of instrumental and vocal knowledge mixed with the rhythmic vivacity of the Baroque period.

The psalm is musically constructed in the alternation of closed pieces, written with contrasting dynamics to capture attention in almost half an hour of music. It should not be surprising that a single psalm could take so long because at the time the spaces of the liturgy were certainly wider and glory was also given to God through the offering of music written by the most talented musicians. Unfortunately we have lost all this in the current liturgy which certainly (and also understandably, in a certain sense) could not allow such long times for liturgical actions but which equally certainly should continue to offer the best of musical production, not what is currently offered to us. But we are all well aware of this problem, even if not much has been done in recent decades to overcome the issues surrounding the liturgical reform. But let us return to our musician.

In Beatus vir it would take a long time to list the valuable pieces, as it would be necessary to name the entire work, from the solemn opening on the first verses of the psalm, to the bass dialogue on the words Potens in terra. From the soprano’s joyful song on Iucundus homo to the triumphant finale that closes the psalm with a sense of jubilant grandeur to the decisive Amen that seals the composition for the glory of God and the edification of the lucky faithful.

An expert on Vivaldi’s production like Michael Talbot writes about him as follows: “Vivaldi’s influence on his contemporaries was enormous. His Concerts definitively established the structure in three movements and the refrain form; they raised the quotient of virtuosity, in particular in the concerts for his instrument, the violin; and they diversified the spectrum of instrumental combinations. On this ground, the Pietà orchestra offered him an exceptional experimental laboratory, with a wide range of solo instruments of all kinds, including rare and exotic ones: violin, modified violin (‘violin in marine trumpet’), viola d ‘amore, viola di gamba (of several types), cello, mandolin, lute, theorbo, psaltery, harpsichord, organ, upright flute (of several types), flute traversiere, flagioletto, oboe, clarinet, chalumeau (of several types), bassoon, trumpet, horn, timpani. In church music he increased the contribution of the instrumental component, while in plays he introduced a seductive faux-naïf style for minor or pastoral roles. More generally, his music enhanced the expressive immediacy and an almost provocative simplicity (for example in the passages in which the orchestra is conducted in unison), which since then became part of the common set of musical language. However, it would be a gross simplification to speak of an ‘escape from counterpoint’: Vivaldi was also an experienced counterpoint expert, capable of conceiving powerful fugues if the context required it. The most illustrious composer directly influenced by Vivaldi was Johann Sebastian Bach, who around 1713 transcribed several of his concerts for the keyboard: but very few contemporary composers, eager to put themselves à la page, disdained his innovations” (treccani. it). In fact, a great admirer of Vivaldi was the almost contemporary Johann Sebastian Bach and this should already say a lot about the enormous value of the work of this composer, a somewhat special priest but certainly an excellent musician who was able to instill in his notes that devotion which, perhaps , he had not been able to show in the exercise of his ministry. We can only say that still today he is hugely popular not only in the very geographical context where western music was born but also elsewhere.

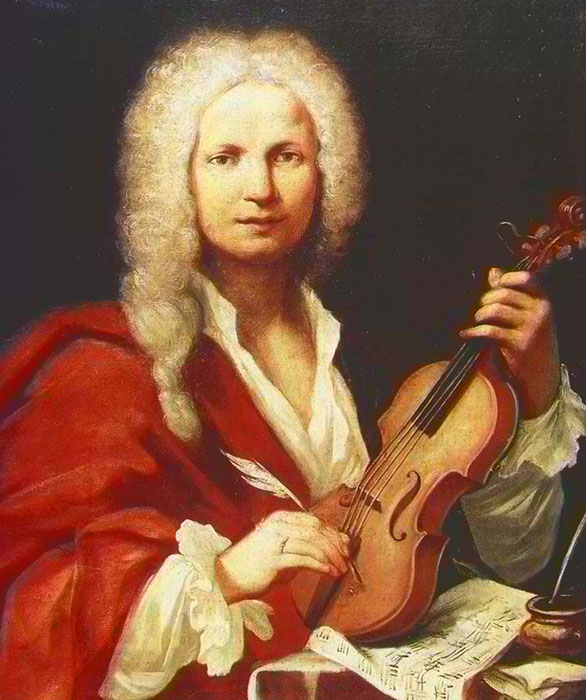

(Image: probable portrait of Vivaldi, c. 1723. An anonymous portrait in oils in the Museo Internazionale e Biblioteca della Musica di Bologna. Courtesy of Wikipedia)

I believe there are few musicians who have a posthumous contemporary fame like the Venetian Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741), who died 280 years ago on 28 July in a situation of near poverty and buried in a mass grave in Vienna, where he was at that time. He was then almost forgotten and revived in the past century. He was a great protagonist of the instrumental season of the Baroque, of which he embodied the merits and even the excesses.

He was ordained a priest, although it seems that in this sense he was quite peculiar, preferring the stages of the opera houses to his liturgical and pastoral duties. He was ordained in 1703 but due to poor health it seems he almost immediately obtained the dispensation from his priestly obligations to devote himself completely to his activity as a musician (and this would partially justify the above fame). He was active in various fields of composition, such as opera, but had great resonance in the field of instrumental music, especially for his concerts written for the talented students of the Ospedale della Pietà in Venice, in which he was active for many decades and for which he composed much of his music.

Alongside his instrumental and operatic production, his production in the field of sacred music was not secondary, a production still widely present today in the concert programs of various musical institutions around the world. As an example we propose the psalm Beatus Vir RV 597 (he composed various versions of this psalm) for 2 soloists, double choir and double orchestra, one of his works rightly more famous from him. The version of Psalm 111 of the “red priest” (as he was nicknamed because of the color of his hair) is a concentrate of instrumental and vocal knowledge mixed with the rhythmic vivacity of the Baroque period.

The psalm is musically constructed in the alternation of closed pieces, written with contrasting dynamics to capture attention in almost half an hour of music. It should not be surprising that a single psalm could take so long because at the time the spaces of the liturgy were certainly wider and glory was also given to God through the offering of music written by the most talented musicians. Unfortunately we have lost all this in the current liturgy which certainly (and also understandably, in a certain sense) could not allow such long times for liturgical actions but which equally certainly should continue to offer the best of musical production, not what is currently offered to us. But we are all well aware of this problem, even if not much has been done in recent decades to overcome the issues surrounding the liturgical reform. But let us return to our musician.

In Beatus vir it would take a long time to list the valuable pieces, as it would be necessary to name the entire work, from the solemn opening on the first verses of the psalm, to the bass dialogue on the words Potens in terra. From the soprano’s joyful song on Iucundus homo to the triumphant finale that closes the psalm with a sense of jubilant grandeur to the decisive Amen that seals the composition for the glory of God and the edification of the lucky faithful.

An expert on Vivaldi’s production like Michael Talbot writes about him as follows: “Vivaldi’s influence on his contemporaries was enormous. His Concerts definitively established the structure in three movements and the refrain form; they raised the quotient of virtuosity, in particular in the concerts for his instrument, the violin; and they diversified the spectrum of instrumental combinations. On this ground, the Pietà orchestra offered him an exceptional experimental laboratory, with a wide range of solo instruments of all kinds, including rare and exotic ones: violin, modified violin (‘violin in marine trumpet’), viola d ‘amore, viola di gamba (of several types), cello, mandolin, lute, theorbo, psaltery, harpsichord, organ, upright flute (of several types), flute traversiere, flagioletto, oboe, clarinet, chalumeau (of several types), bassoon, trumpet, horn, timpani. In church music he increased the contribution of the instrumental component, while in plays he introduced a seductive faux-naïf style for minor or pastoral roles. More generally, his music enhanced the expressive immediacy and an almost provocative simplicity (for example in the passages in which the orchestra is conducted in unison), which since then became part of the common set of musical language. However, it would be a gross simplification to speak of an ‘escape from counterpoint’: Vivaldi was also an experienced counterpoint expert, capable of conceiving powerful fugues if the context required it. The most illustrious composer directly influenced by Vivaldi was Johann Sebastian Bach, who around 1713 transcribed several of his concerts for the keyboard: but very few contemporary composers, eager to put themselves à la page, disdained his innovations” (treccani. it). In fact, a great admirer of Vivaldi was the almost contemporary Johann Sebastian Bach and this should already say a lot about the enormous value of the work of this composer, a somewhat special priest but certainly an excellent musician who was able to instill in his notes that devotion which, perhaps , he had not been able to show in the exercise of his ministry. We can only say that still today he is hugely popular not only in the very geographical context where western music was born but also elsewhere.

(Image: probable portrait of Vivaldi, c. 1723. An anonymous portrait in oils in the Museo Internazionale e Biblioteca della Musica di Bologna. Courtesy of Wikipedia)

Follow

Follow