Robaird O’Cearbhaill

Hong Kong Correspondent

Why did the Irish Miracle monkssave Western Europe and the Church from barbarism from the 5th century until the next millennium?

Isn’t it a wonder that a newly-baptized, non-Roman, rural society Island, the last edge of Europe before the unknown Atlantic ocean expanses, became such a cultural regenerative power?

Isolation was partly an influence, and the arrival of high Western culture. Roman scholars, bringing their valuable educational books, found refuge from violence and disorder on the continent in Ireland.

Moreover, Ireland was still an agricultural country – it had no towns yet. The Irish missionaries were farmers, dedicated to poverty, and the poor. Christianity, and with that Latin learning, had opened their minds. That breakthrough, untainted by Roman pride and sense of superiority, opened their hearts to Catholic charity to evangelize the invading pagan European tribes.

Very crucial for emigrating Irish scholars, was adopting the classic languages Latin and Greek for learning. There was no other choice as no other European languages were written then. All superior education in Europe had to be in Latin, except in the Greek-speaking Eastern Roman empire. Irish monks were skilled copyists, and soon many of them became fluent in formal Latin. That opened doors in every former Roman province. For leading families, Spanish, French, Italian, and Portuguese were out of favor compared to classical Latin. Many of the new rulers welcomed them as tutors and interpreters.

The monks’ mission was entitled Peregrinatio pro Christo, Exiles for Christ, following the evangelist of all Ireland in the 5th century, St Patrick, a British Roman. St Patrick was the most successful Exile for Christ there and head of the Irish Church. Luck for Ireland was that St Patrick had been captured by Irish pirates and sold into slavery in Ireland. It was very hard on an educated Roman teenager to become a very badly treated animal herder, but he learnt the language, liked the Irish and forgave the slave traders. St Patrick brought British Roman Catholicism to the majority even though soon local rules differed from Britain and continental communities.

Roman Emperor Constantine allowed Christianity to flourish in the empire in the 4th century but once the Western empire fell after multiple, conquering, nomadic invasions from Germany and beyond, chaos descended on the former Roman Europe. With many Christians not being able to receive the sacraments, the weakened Church was fragile. A widespread solution was needed. Fortunately, the Irish Exiles for Christ, brought back stability over several centuries, through their monasteries in Northern, Central and Southern Europe.

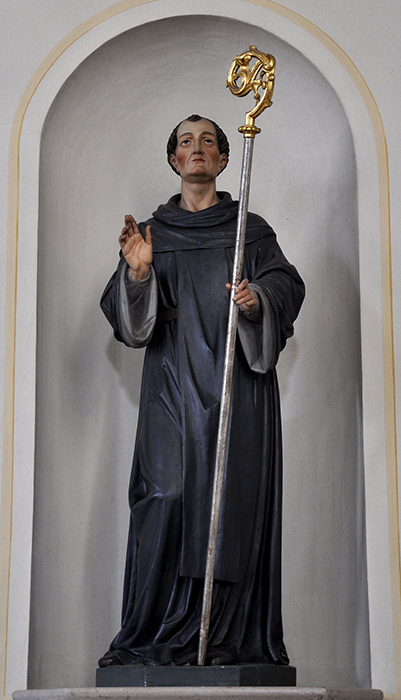

In the Irish Matryoshka: A History of Irish Monks in Medieval Europe by Irish historian James J Harkin (Seamus O OhEarcain), he tells “the story of Ireland as an essential part of the European historical scene and not as some backwater island on the periphery of the then-known world…in the context of those events that shaped western ideals in the Middle Ages.” (Photo: St Columbanus, born 540 AD. Ireland. Missionary in France 590 AD and later in Switzerland and Italy.)

Follow

Follow