Joseph Sta Maria – Photo by Marco Carvalho

– Marco Carvalho

Promotor of the the Luso-Asian Communities Conference, Joseph Sta Maria became, over the past few years, a respected representative of the community of Portuguese-descendants of Malaysia. The “Portuguese of Malacca” have their own language and dishes with slightly European connotations, but the characteristic that best defines the community is religion. Community members have kept Catholicism alive for more than five centuries and such perseverance qualifies them as the custodians of Catholic faith in Malaysia, Mr Sta Maria told O Clarim.

For the Portuguese community of Malacca, the Catholic religion is one of the aspects that sets it apart from the rest of the Malaysian population. It’s a strong trait of identity. How important, for the Malaccan Portuguese community, is Catholicism?

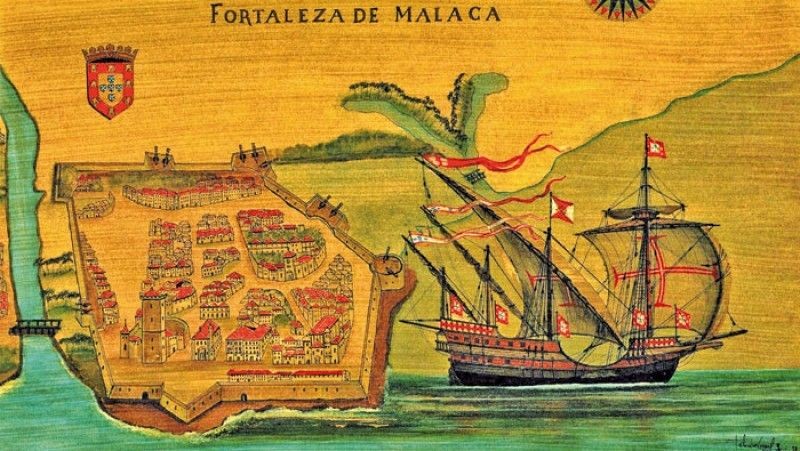

When the Portuguese arrived in Malacca, they had in mind what we call the “three-G’s”: God, Gold and Glory. By God they meant spreading their religion. The Portuguese did not come to Malacca with any women. When they came, they were all men. They brought with them people from Goa, of course, but they intermarried with the locals. The King of Portugal, D. João, emitted a decree in which he encouraged mix marriages and in which he allowed the Portuguese to produce new breeds wherever they went. It was part of the policy adopted by Portugal then. A conqueror that actually left his mark in Malacca was Afonso de Albuquerque. After the conquest of Malacca, he rewarded his soldiers by allowing them to marry the locals. What I am saying is that there was this policy that produced people like me, a mestizo community. As far as Malacca is concerned, we see ourselves as the Malacca Portuguese community, but you find other communities of Portuguese origins in the nooks and corners of the Indian Ocean: Sri Lanka, Macau, Goa, Daman, Diu. You will find this sort of people even in Vietnam. But, as far as Malacca is concerned, the Portuguese community festivities are very Catholic festivities. The biggest celebration we have is San Pedro – the feast of Saint Peter – the patron saint of the fishermen. This feast had a very humble beginning, but today it is part of the national tourism promotion strategies. We consider it a celebration of our community. And then we have “Natal,” which is Christmas. If you look at the way Christmas is celebrated in the village you will understand how different it is. You wouldn’t find anywhere in Malaysia that kind of vibrancy, that kind of festive mood.

You mentioned Festa San Pedro. You were saying it is a special occasion not only for the Portuguese community, but also for the people of Malacca. It became a sort of tourist attraction. What about in the rest of the year? Can we still see churches with a full attendance in Malacca? People still pray the rosary in their homes?

In Malacca the churches are always full. But it’s more than that. Look at the Portuguese settlement: we all live practically in one street. There are seven hundred of us, the descendants of the Portuguese community. Of course, there are other members of the community that live elsewhere in Malacca, but those that are concentrated in the Portuguese Settlement number between 700 to 800 people and there’s a rosary that goes from house to house every three days. This is not something recent. It is something that has been happening for years, decades. Mother Mary goes from house to house and after three days in each house, the family prepares something to eat for their guests. This is something that only happens within the community. On Sundays, the Church is always full and the same happens at the Church of the Immaculate Conception. And we don’t have enough priests. The priests are not sufficient. The Catholic faith, as it is lived by the Catholics in Malacca, is very strong. Of course we are not a majority neither in the country, nor the State. We are part of a very small minority, but we are still very visible as a community: the Churches are full, the devotion is very strong and Catholicism is still very steady, unlike what is happening in Europe, where most of the Churches are empty. And this is where we felt some apprehension. We are very concerned with the erosion of the Portuguese community Catholic rituals and traditional celebrations. We also have our own problems within the Catholic Church: young priests of non-Portuguese descent have to understand the historical dimension of the community and the links that it has with the Portuguese culture. Sometimes new converts will become Catholics and these priests do not understand the weight of the Catholic traditions of the Portuguese community. This has led to some misunderstandings.

Are there any priests nowadays among the members of the Portuguese community?

There are, there are. But they don’t serve in the Portuguese Settlement. They are around Malaysia. There are only a few. Within the Portuguese community we always had more nuns than priests. My auntie was a nun. She passed away already, a couple of years ago. Several girls from the Portuguese community became nuns. Within the Portuguese settlement, within our village we have none, but within the outskirts of the village there are one or two, but they have passed away or they are elsewhere, serving in other States. Sometimes, it is very difficult for us. The Portuguese traditions are always very sacredly held by the community. We used to have Portuguese priests from Portugal. The last of them was…

Father Pintado?

Father Sendim. Pintado was an historian. He was an amazing man, you know? His contribution to the Portuguese community of Malacca is extraordinary. Without him, we would have lost a lot of our stories. Father Pintado was amazing as an historian, but the last Portuguese priest that we had was Father Sendim. He could interact with the youth like no one else. Thanks to him, they were able to understand the Portuguese traditions. I am worried. The Church must understand our traditions. For instance, we had a few issues… There is a big church in Malacca, Saint Peter’s Church. Last year, they wanted to have the Mass in the Church rather than in the village. This never happened before. We said: “No. We must have it in the village, because it has always been like that in the past.” The priest told us that Saint Peter’s Church was the Mother Church of our community. We never had any issues in the past. We conveyed our opposition very clearly and in a very polite manner and he allowed us to do what we have always done. Nevertheless, for how long can we fight this battle? How long do we have to remind them about our values and to witness the erosion of the Portuguese identity? Saint Peter’s Church is the mother Church of the Portuguese community, but we are afraid, eventually, of it becoming eroded even further. We have this brotherhood of the Church. It is a Dominican sect that has survived for four hundred years. We call it “Irmãos de Igreja.” The Dominicans established it in the 16th century. They gave away their own old chapel; they went to Saint Peter’s Church and merged. After four hundred years, their cultural and religious rights over the Church are still recognized, but we are afraid. In the past, the previous Portuguese priests were well aware of these rights and they understood them. I am not against the new priests. I am just saying there must be a form of understanding and they need to respect the traditions of the Portuguese community.

You told me previously that the members of the Portuguese community see themselves as the guardians, the custodians of Catholicism in Malaysia…

Yes, yes. I said that because it was our ancestors that brought the religion here. When the Dutch conquered Malacca in 1641 and got to rule it, after 130 years of Portuguese domination, there were no Portuguese from Portugal anymore. There were people like me, local Portuguese of second or third generation. The community evolved at that time. It was that brotherhood, the “Irmãos de Igreja” and all the remaining members of the Catholic community, that kept the faith alive, despite the persecution of the Dutch. They took refuge in their own homes and conducted secret services to keep their religion alive, until the European War of Secession was settled. After the war came to an end, the Dutch allowed Catholicism to be practiced, but this happened only after fifty years. Only then the Portuguese community was, once again, allowed to practice the Catholic religion. That period of time was very hard: there were persecutions and Catholicism was prohibited, because the Dutch were Protestants. These people, who were the descendants of the original Portuguese community, kept the religion alive. Up until today, it was their faith that kept Catholicism alive. Without them, we wouldn’t be a strong and proud community in Malaysia. The Catholic Church might not want to accept us as the custodians of the Catholic religion, but I think that my ancestors and my community were and still are the custodians of Catholic faith in Malaysia. The Catholic Church must understand this. We are very happy, nevertheless. I think that the relationship between Malacca and the Vatican is very strong and it always was, ever since the 16th century. There were letters written between the Malacca Portuguese Governors, the Pope and the King of Portugal. At that time, Portugal and the Vatican were very close. If you look at Father Manuel Teixeira’s book, when Malacca fell in the hands of the Portuguese, King D. Manuel informed Pope Leo X that Malacca was in the hands of the Portuguese and the Catholic faith. The Pope actually had a celebration in the Vatican to commemorate the fall of Malacca. I know this is history and we are a minority within the minorities of Malaysia, but the significance of the Malacca Portuguese descendants to the Vatican is very, very strong.

You mentioned other Eurasian communities with Portuguese roots, like the Burghers, in Sri Lanka, like the Macanese, in Macau. All of them have one thing in common: the Catholic faith. Do you see Catholic faith as a sort of a brotherhood builder within this sort of community?

In my opinion, the Catholic faith is the pillar of our community. As I said, the community’s festivities are all linked to the Catholic faith. If the Catholic faith was not a part of the package – the “3G’s” that I mentioned before, God, Gold and Glory – if God was not there, I think we would have already disappeared. Look at the Dutch; look at the English that came to Malacca and to several other parts of Asia. They came with God neither in their mind, nor in their heart. They merely came to trade. The Dutch belonged to the Reformist Church, they were Protestants. They were not interested in Evangelization. Their own interest was to trade. The Protestant religion did not last in Malacca. The Dutch rule over Malacca was longer than the Portuguese rule, but nowadays we don’t find any Protestants in Malacca today and there are a few families with Dutch surnames that are members of the Portuguese community today. Why is that so? Because they were assimilated to the Portuguese community, accepting the Malacca Portuguese culture and this Malacca Portuguese culture includes the religion. You were talking about the Burghers and all the rest. What is the pillar of their survival? The pillar of their survival is Catholicism. They have maintained Catholicism, they have rooted it in their own culture. It’s a religion and they have been practicing it, but it is something more, because they have developed their own traditions. And this is what I was saying: the Catholic Church, the Catholic community must respect these traditions, because these people were the ones that kept this traditions alive.

In the case of the Portuguese community of Malacca there‘s another curiosity, which is the fact that, the other strong trait of identity for which you are known has a very Catholic name also: “kristang.” The vernacular language that the community kept alive during four centuries already identifies the community as being different from the rest of the Malaysian population…

Colloquially speaking, within the community, sometimes we say: “Vôs kristang,” you are kristang. “Kristang” means Christian. Within the Portuguese Settlement there were other communities living: the Chinese, the Indians. They used to live in the outskirts of the settlement. When they referred to us, they would say “genti kristang.” They wouldn’t call us Portuguese at the time, but within the community, we called ourselves the Malacca Portuguese. And there’s not a “kristang” language, there’s not a “christian” language. So, what do we speak? There was recently a debate, because in Singapore a few Eurasians used to call it “kristang” language, but the language that they speak was originally from Malacca. It is the Malacca Portuguese language. If you say that it’s not Portuguese language you are deceiving yourself. Alan Baxter says it is not Portuguese, he says it is a creole, but I cannot agree with him. Let’s put it this way: 90 per cent of the “língua franca” that we speak is Portuguese based. The words are originally from the Portuguese language. What is wrong in calling it the Malacca Portuguese language? Why should we call it “kristang” and play with the sense of the words? And you tell me, which language nowadays is not a creole? Even the national language of Portugal is somehow mixed today. There are a few words that were borrowed from other languages. Even the English language is not one hundred per cent pure. I dare to say that 90 per cent of the language that my ancestors spoke and that I speak are Portuguese in origin. I am not a linguist, but it seems to me that linguists want us to believe what they believe. Go and listen to the people. You will understand by yourself what is it that they speak.

Follow

Follow