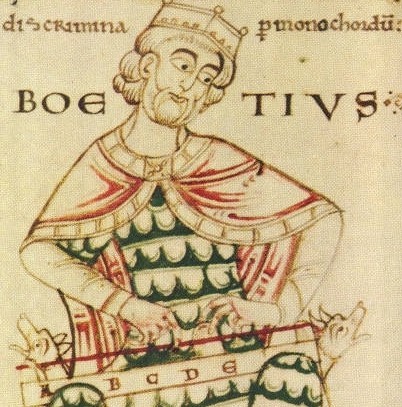

When we speaking about Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known as Boethius (477-526?), we are speaking of one of the greatest minds of Christian philosophy.

He was born in Rome from the gens Anicia, a family that has given to the Church great figures as Saint Benedict and Saint Gregory the Great among others. He was a civil servant of the state, at that time in the hands of Barbarian rulers after the fall of the Roman empire in 476. Among his most important works we have De consolatione philosophiae. He was also hugely important and influential for the development of music theory in the middle ages, subdividing music in three categories: mundana (the music of the spheres), humana (the music of the connection between body and soul) and instrumentalis (the music actually performed). This concept will be very important and will also introduce the idea of music as a way of knowledge, a concept that was certainly known as well to the earliest Church Fathers.

He was very influential also on Cassiodorus, another great thinker of the time, as we can see from this entry in britannica.com: “When Cassiodorus founded a monastery at Vivarium, in Campania, he installed there his Roman library and included Boethius’s works on the liberal arts in the annotated reading list (Institutiones) that he composed for the education of his monks. Thus, some of the literary habits of the ancient aristocracy entered the monastic tradition. Boethian logic dominated the training of the medieval clergy and the work of the cloister and court schools. His translations and commentaries, particularly those of the Katēgoriai and Peri hermeneias, became basic texts in medieval Scholasticism. The great controversy over Nominalism (denial of the existence of universals) and Realism (belief in the existence of universals) was incited by a passage in his commentary on Porphyry. Translations of the Consolation appeared early in the great vernacular literatures, with King Alfred (9th century) and Chaucer (14th century) in English, Jean de Meun (a 13th-century poet) in French, and Notker Labeo (a monk of around the turn of the 11th century) in German. There was a Byzantine version in the 13th century by Planudes and a 16th-century English one by Elizabeth I.”

It would be very difficult to evaluate the influence of this thinker on following philosophers and Christian thinkers. Because, we should not forget it, he was first and foremost a Christian thinker: “That he was a Christian is proved by his theological tracts, some of which, as we shall see, are undoubtedly genuine. That he remained a Christian is the obvious inference from the ascertained fact of his continued association with Symmachus; and if the Consolations of Philosophy bears no trace of Christian influence, the explanation is at hand in the fact that it is an entirely artificial exercise, a philosophical dialogue modelled on strictly pagan productions, a treatise in which, according to the ideas of method which prevailed at the time, Christian feeling and Christian thought had no proper place. Besides, even if we disregard certain allusions which some interpret in a Christian sense, there are passages in the treatise which seem plainly to hint that, after philosophy has poured out all her consolations for the benefit of the prisoner, there are more potent remedies (validiora remedia) to which he may have recourse. There can be no reasonable doubt, then, that Boethius died a Christian, though it is not easy to show from documentary sources that he died a martyr for the Catholic Faith. The absence of documentary evidence does not, however, prevent us from giving due value to the constant tradition on this point. The local cult of Boethius at Pavia was sanctioned when, in 1883, the Sacred Congregation of Rites confirmed the custom prevailing in that diocese of honouring St. Severinus Boethius, on the 23rd of October.” (Turner, W. “Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius.” In The Catholic Encyclopedia: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02610b.htm).

Walter John Sedgefield has given a version in English of the masterwork by Boethius. Here is a passage: “The songs that I, poor exile, once sang so merrily I must now croon sadly sighing, and make of unmeet words. I who of old did oft so deftly weave them, now ever the fitting words I fit awry, weeping aye and sobbing. ‘Tis faithless prosperity hath dimmed my sight, blinding me and forsaking me in this sunless cell, and that to which I ever trusted most hath robbed me of all my joy. It hath turned its back upon me and utterly fled from me. Why, oh why, did my friends tell me I was a happy man? How can he be happy that cannot abide in happiness?” Certainly, this is one of the great masterworks of Christian literature.

Follow

Follow