– Anastasios

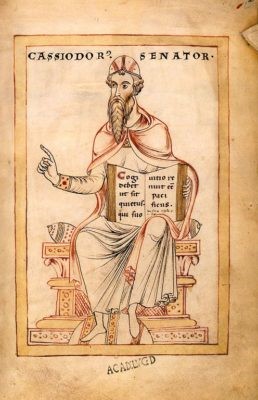

One of the most influential thinkers in the time of the final decadence of the Roman Empire was Flavius Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus (485-585). He was born in southern Italy in a family that was traditionally at the service of the state. So our Cassiodorus will serve the state for a certain time of his life until he decided that he preferred monastic life. He was the founder of the Vivarium monastery, also in southern Italy, where he dedicated himself to a rich spiritual and cultural life. He was fond of studying Christian authors as the Church Fathers, but also authors from the pagan world, a tradition that will be well respected in the Benedictine monasteries.

He is the author of several important and influential works, and some of them will have also an influence in Church music and in education: “Of all the work achieved by this author in the monastic retreat, what we of today find most interesting is the Institutiones divinarum et sæcularium litterarum, written between 543 and 555. His object was to furnish the monks with means of interpreting Holy Writ, but the plan of study which he suggests is far in advance of simple meditation on the Bible. He demands the reading of commentators, of Christian historians, to whom he adds Flavius Josephus, of chroniclers, and of the Latin Fathers. He recommends the liberal arts; he proclaims the merit gained by those who copy the Sacred Books, and outlines the rules to be followed in the correction of the text. Finally, in a second part, he resumes the theory of the liberal arts by following the division worked out by St Jerome, Martianus Capella, and St Augustine. He distinguishes the arts, notably grammar and rhetoric, from the sciences, which are arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy. Dialectics, to which he attributes great importance, he considers part art and part science. Of course, Cassiodorus subordinates the profane studies to theology, but, unlike Isidore, for example, his extracts and compendiums do not dispense the monks from making further researches; they rather provoke such research by referring to books with which he was careful to equip the convent library. It had been his dream to found the first theological faculty in Rome; at least he had the merit of putting in the first rank of monastic occupations intellectual work, to which St Benedict had allotted no place. During his public career Cassiodorus endeavoured to reconcile two races, the Goths and the Romans; in his religious retreat he laboured with greater success to harmonize the culture of the ancient with that of the Christian world. Modern civilization was the outgrowth of the alliance brought about by him” (Lejay, P, & Otten, J (1908). “Cassiodorus.” In The Catholic Encyclopedia. New Advent: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03405c.htm).

Benedict XVI, in the audience of March 12, 2008, spoke about Cassiodorus: “The search for God, the aspiration to contemplate him, Cassiodorus notes, continues to be the permanent goal of monastic life (cf. PL 69, col. 1107). Nonetheless, he adds that with the help of divine grace (cf. PL 69, col. 1131, 1142), greater profit can be attained from the revealed Word with the use of scientific discoveries and the ‘profane’ cultural means that were possessed in the past by the Greeks and Romans (cf. PL 69, col. 1140). Personally, Cassiodorus dedicated himself to philosophical, theological and exegetical studies without any special creativity, but was attentive to the insights he considered valid in others. He read Jerome and Augustine in particular with respect and devotion. Of the latter he said: ‘In Augustine there is such a great wealth of writings that it seems to me impossible to find anything that has not already been abundantly treated by him’ (cf. PL 70, col. 10). Citing Jerome, on the other hand, he urged the monks of Vivarium: ‘It is not only those who fight to the point of bloodshed or who live in virginity who win the palm of victory but also all who, with God’s help, triumph over physical vices and preserve their upright faith. But in order that you may always, with God’s help, more easily overcome the world’s pressures and enticements while remaining in it as pilgrims constantly journeying forward, seek first to guarantee for yourselves the salutary help suggested by the first Psalm which recommends meditation night and day on the law of the Lord. Indeed, the enemy will not find any gap through which to assault you if all your attention is taken up by Christ’ (De Institutione Divinarum Scripturarum, 32: PL 70, col. 1147). This is a recommendation we can also accept as valid. In fact, we live in a time of intercultural encounter, of the danger of violence that destroys cultures, and of the necessary commitment to pass on important values and to teach the new generations the path of reconciliation and peace. We find this path by turning to the God with the human Face, the God who revealed himself to us in Christ.”

Cassiodorus reminds us of the importance of culture, the importance of carefully studying the way the world evolves. It is a lesson that was valid not only in medieval times.

Follow

Follow