– Aurelio Porfiri

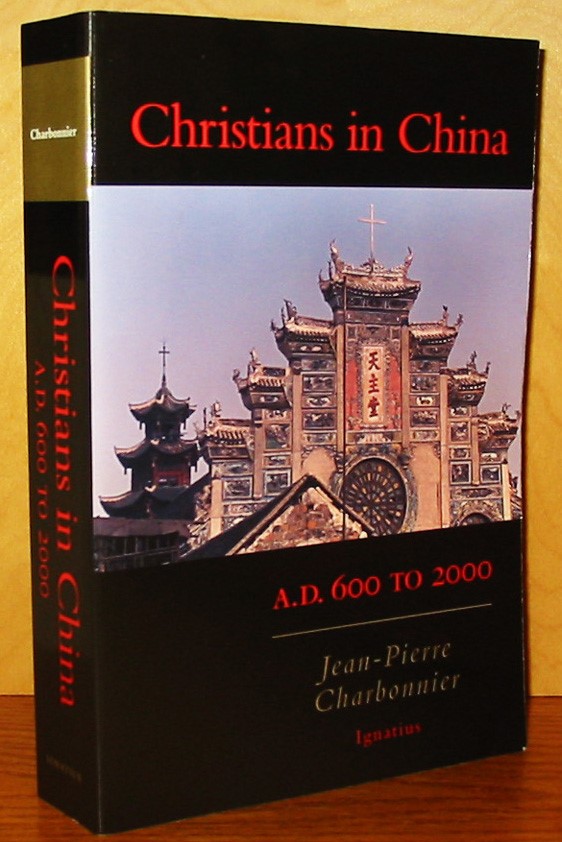

One of the reference books for those who want to know about the evolutions and involutions of Christianity in China is Christians in China, by Father Jean-Pierre Charbonnier MEP, also available in English from Ignatius Press. An important and voluminous book that gives us a very good idea of the struggles and efforts to bring China to Christ and Christ to China.

What is the origin of your interest on China?

I was in my teens when my interest in China was aroused through the reading of a thick book, Histoire de la Chine by Rene Grousset. I devoured it like a novel and found it fascinating. It was a kind of dream trip along the silk road through high mountain pass and vast desert lands. The art of ancient China drew my attention. Visits to the Paris museums Guimet and Cernuschi made me discover Chinese farmers’ daily life under the Han dynasty and the splendours of the Tang court at a time when our Western Europe was slowly taking shape under the leadership of Charlemagne. My army national service in the holy Muslim city of Kairouan in Tunisia offered me opportunities to broaden my horizon. I had learned to read the Bible in the original Hebrew text. I learned the Arabic alphabet and could identify a number of words of the same semitic root. I made a deeper inquiry into Islamic faith and rituals. It led me to a better understanding of our Judeo-christian tradition. A close friend in Versailles seminary happened to be a great fan of China. He made me share his enthusiasm. When we studied philosophy in the major seminary, two other fellow students joined the Paris Foreign Mission society. I decided to follow their way.

Can you tell us where you have lived in Asia?

During the spiritual retreat which preceded my ordination to priesthood, I received a phone call from our superior in Paris. He announced to me that I was destined to the Singapore mission. I was delighted, knowing that the Singapore population was 75% Chinese. Ordained priest in December 1957, my departure to the East was delayed by two more years as I had to prepare four certificates in Sorbonne University and obtain a license for teaching philosophy. After three weeks sailing through the Suez Canal, Aden, Bombay, Colombo, I reached the green islands of Singapore a few days before Christmas 1959. On board the ship Cambodge I kept busy with the handbook Teach yourself Malay. I was able to use a few greeting words when landing. Posted at the Good Shepherd Cathedral, I spent a year learning Malay and practicing English. The following year, the archbishop of Malacca-Singapore sent me to a language school in Kuala Lumpur to learn Mandarin, one of the 4 languages officially used in Singapore, the 4th language being the Indian Tamil. After a year of intensive language study in Malaysia, I was back to the new parish of St Bernadette in Singapore and could slowly improve my Chinese language through practicing it with youth and family groups and with catechumens preparing for baptism. During my first decade in Singapore, I took advantage of holiday times to visit Thailand, Vietnam, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Cambodia, Japan and South Korea. In 1967, a long holiday took me around the world for a visit of Chinese friends of the “diaspora” in Europe, Canada and the States.

You wrote a book that is a reference for studies on China and Christianity: Christians in China. What are other books would you consider useful references about Christianity and China?

In 1970, I was called back to Paris to teach theology in the Inter Missionary Institute called “CERM, Centre d’Etudes et de Recherches missionnaires”. While renewing my reflection in philosophy and theology at the Catholic Institute of Paris, I registered again in the Sorbonne University for further research in Chinese. I wrote a thesis on the modern Chinese writer Lu Xun, a pioneer in the “New Literature” eager to make his people more active and responsible in the general struggle for a better life. Fr Leon Trivière, MEP, a missionary in China from 1946 to 1950, later had spent a decade in Hong Kong, closely observing the evolution of the Church in the Mainland under the new communist regime. He published precious articles in our MEP Bulletin. Despite all the sufferings endured, he was passionate for the new China and believed in a bright future for China. Back to Paris since the early 60es, he was writing articles on the actuality in the Asian countries. In early 1974, he drew my attention to the Church situation in China. In November 1971 the People’s Republic of China had entered the United Nations and a church had opened in Beijing for foreign Catholics. Protestants and Catholics organized a colloquium in Louvain in September 1974 to reflect on the new China experience and its theological implications for the Church. Trivière invited me to cooperate with him in producing a paper for this colloquium. The MEP published it under the title: “Mao’s challenge to Christians” Personally, I thought that China’s revolution included many positive aspects, even for the Church. The expulsion of the some 5000 foreign missionaries, bishops, priests and religious had been a cruel experience, but it allowed Chinese priests and sisters to take charge of the future of their China Church. They needed to draw inspiration from their China Christian history. The more urgent task was not a new history of the missions in China. We had to bring to the fore the contribution of the Chinese themselves in spreading the Gospel and developing a Church life of their own. I resolved to bring my attention to the growth of the China Church from its early developments in the 7th Century under the Tang Emperors. I stressed the role of the Ming and Qing scholars who studied the Jesuits’ message in the 17th and 18th centuries. In the 19th Century, the influx of Western missionaries and the French protectorate unfortunately seemed to transform China Church’s growth into a foreign enterprise. But in fact a huge groundwork was achieved in rural areas by the Chinese catechists, virgins and heads of communities. In summer 1900, thousands of them stood for their faith in Christ Saviour and were slaughtered by the Boxers. Eighty-three lay people are numbered among the 120 martyrs of China canonized by Pope John Paul II on the 1st of October 2000. In 2000, I published another book specially consecrated to these 120 martyrs of China.

We were mentioning your book….

My History of the Christians in China was first published in 1992 by A Fayard. M Geng Sheng from Beijing, a great translator of French books, then met me at the Chantilly colloquium and asked for my book to be translated into Chinese. It was published in 1998 by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and made available in all the Xinhua bookshops. A second French edition with improved appendices was published in 2002. My former schoolmate in the Versailles Seminary, archbishop of Birmingham Maurice Couve de Murville, decided to produce an English translation. It was published in 2007 by Ignatius Press in San Francisco under the title Christians in China, 600-2000. In the Chinese world, “Christian” means “protestant.” Many who bought this English book discovered a lot of the Chinese Catholic history. My book was written for the general public. More accurate details can be found in the two volumes of the Handbook of Christianity in China published in Leyden under the care of the Jesuit Nicolas Standaert.

You are a priest of the Missions Etrangères de Paris. Can you tell us what was the role of your congregation in the evangelization of China?

The main purpose of our MEP missionary Institute was to develop in China and East Asia a structured local Church with its bishops and priests. It started with the appointment by the Pope in 1658 of Apostolic Vicars who were consecrated bishops and sent to vast regions of East Asia. The first to reach Asia in 1662 was Mgr Lambert de la Motte. He could settle in Ayudhya, the capital city of Siam. His first care was to open a seminary for the training of Asian priests. Andrew Li and other Chinese priests were trained there in the early 18th Century. Three hundred years later, this Seminary called “College general” was still active in Penang Malaysia. Over the past three centuries it had trained 70 Asian bishops and some thousand Asian priests. In China, our MEP society was particularly active in remote villages among poor Chinese farmers and ethnic minorities. Our missionaries were coming from large families of the French provinces. A few benefited from higher studies or from professional expertise. They contributed to local rural development in building roads and bridges, improving irrigation or importing agricultural products, opening local pharmacies and clinic for medical care.. Most of all, they produced local language dictionaries, grammars or even local script when dialects were purely spoken without any letters or signs. They trained people in the Christian faith through catechists and virgins. Experienced catechists could eventually be called to priesthood with complementary training in theology and Latin. The virgins were consecrated women living in their families. Well trained, they could do a lot in the instruction of women and even open girls schools when there were none in the country. Chinese women became more aware of their role in society thanks to their catholic education. Most of our MEP missionaries lived the incarnation of Christ in sharing the life of the poor farmers, caring for their health and well being. They shared their sufferings, giving a concrete testimony of God’s saving Love.

Follow

Follow